Gulf of Guinea Nations Gather in Ghana to Forge Partnerships Against Maritime Crime

An oil tanker carrying nine crew members sailed through the Gulf of Guinea off the coast of Nigeria in January 2015. Soon, the vessel fell victim to a common regional threat.

Near Warri, Nigeria, eight heavily armed pirates boarded the ship, bound for a port in Togo, and took command. From there, the MT Mariam continued its course up the West African coast. Much of this journey is shrouded in mystery.

At some point, pirates must have sidled the Mariam up next to another vessel operated by accomplices. The two crews worked together to drain the Mariam of the 1,500 metric tons of crude oil it was carrying. Forces from Benin, Ghana, Nigeria and Togo searched for the ship with the stolen cargo, Reuters reported.

As the ship passed through Togo’s territorial waters into Ghana’s maritime domain, something very simple — but vitally important — happened: Togo’s chief of naval staff picked up the phone and rang his counterpart in Ghana, Rear Adm. Geoffrey Biekro.

Biekro assured his colleague that he would take care of the matter. The GNS Blika, led by Lt. Cmdr. Michael Duvor, was dispatched to the hijacked ship 26 nautical miles southeast of the Ghanaian port city of Tema, Ghana’s Daily Graphic reported. There, Ghana’s Navy captured the ship without injury to crew members, criminals or Sailors. The Navy recovered four AK-47 assault rifles, 300 rounds of ammunition, one pump-action gun, 18 mobile phones, nearly $1,500 and three hand-held VHF radios.

Just two months earlier, Biekro had sailed two Ghana Navy ships to Togo and Benin as a Navy band played on board. At each stop, Biekro and his naval counterparts discussed joint training, exchange visits, and information and intelligence sharing. The commanders signed communiques with each other solidifying their commitments.

“Very soon we shall start joint exercises at sea, and we also discussed hot pursuit into others’ territorial or others’ exclusive economic zone, which will be approved by our respective governments,” Biekro told ADF. “But in all this, the commitment, the enthusiasm of my counterparts made it clear that we are on the way to big success.”

THE POWER OF PARTNERSHIPS

West Africa’s maritime area is vast, with shoreline stretching from Angola to Senegal. It includes the Gulf of Guinea, where a wide range of commerce and crime intersect, sometimes with violent consequences. Many West African navies are limited in their capacity to effectively patrol their territorial waters and exclusive economic zones, which stretch 200 nautical miles from shore.

The Ghana Navy’s overtures to Togo and Benin in November 2014 and Biekro’s visit to his counterpart in Côte d’Ivoire in February 2015 to foster cooperation and information sharing are examples of the possibilities.

“The criminals take advantage of our ill-defined international maritime borders to commit crimes in one country and immediately move into other countries’ territorial waters to escape arrest,” Biekro said.

Accra, Ghana, became a hub of maritime cooperation in March 2015 with two major events. First, the Coastal and Maritime Surveillance Africa (CAMSA) conference brought together senior naval officers and international maritime security experts and vendors to discuss best practices and available technology for protecting the maritime domain.

A few days later, Exercise Obangame Express 2015, a multinational naval exercise, began in the Gulf of Guinea.

AN EXERCISE BUILT ON TOGETHERNESS

“Obangame” comes from the Fang language of southern Cameroon and other parts of Central Africa. It means “togetherness,” an apt name for the event in the Gulf of Guinea. U.S. Africa Command sponsors the annual exercise, which brought together 23 countries: Angola, Belgium, Benin, Brazil, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Denmark, Equatorial Guinea, France, Gabon, Germany, Ghana, Nigeria, Norway, Portugal, the Republic of the Congo, São Tomé and Príncipe, Spain, Togo, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States.

The exercise had multiple purposes and multiple layers. Its intent was to help African nations put into operation the Yaoundé Code of Conduct, signed in Cameroon in June 2013 by more than 20 West and Central African nations. Through it, nations agree to cooperate on maritime security by sharing and reporting information, interdicting vessels suspected of illegal activities, apprehending and prosecuting criminals, and caring for and repatriating seafarers subjected to illegal activity.

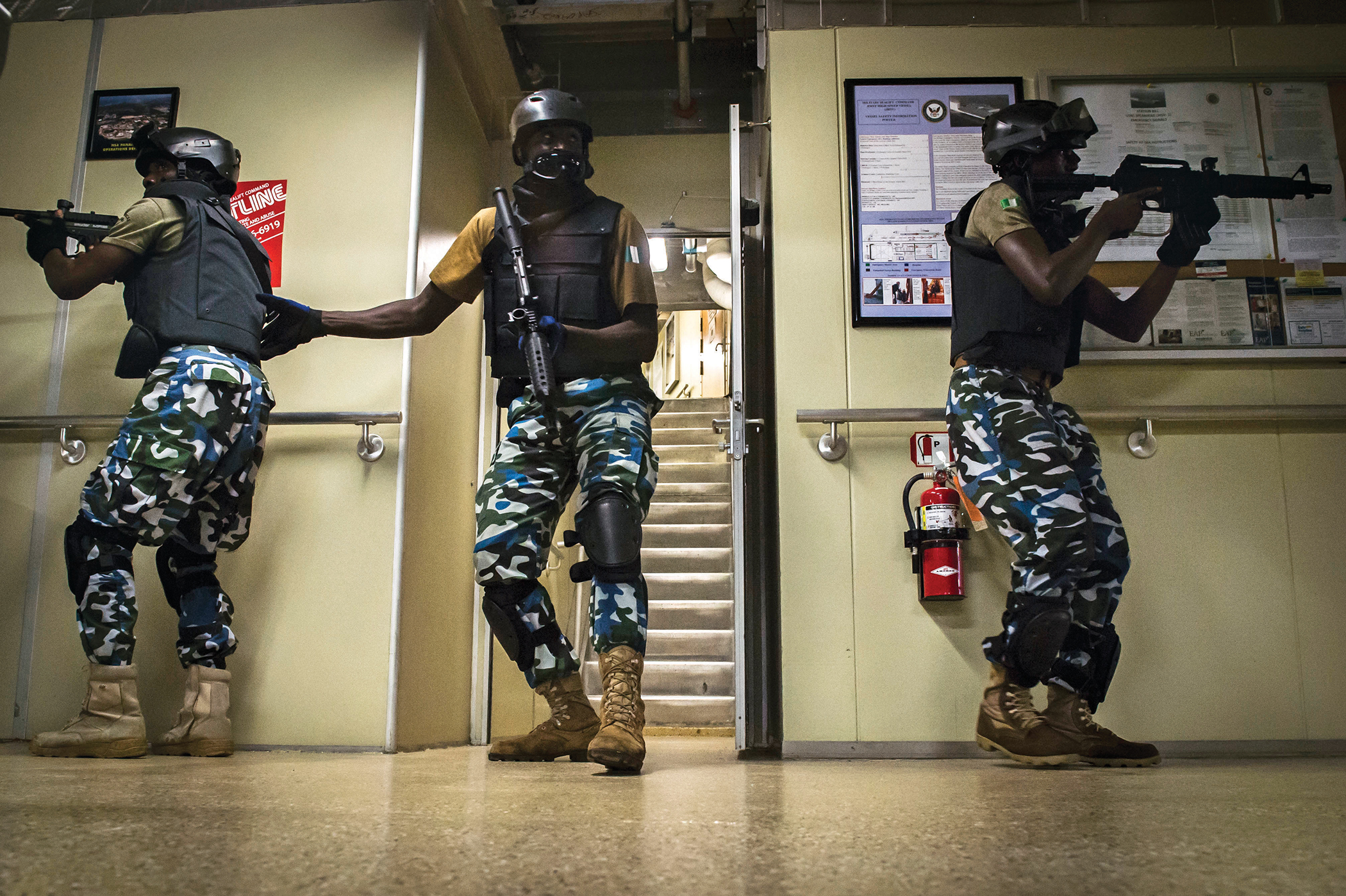

Obangame Express tested and bolstered these capabilities in several ways. Four major scenarios played out at sea using large ships from the United States, Brazil and European nations. Two involved oil tanker hijacking. One mimicked weapons smuggling, and the other simulated illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing.

These scenarios played out across the water from Angola to Ghana and included eight large ships. Personnel working in national marine operations centers (MOCs) tracked the ships as they moved along coastlines. The scenarios tested individual nations’ abilities to do this while responding to injects from a multinational exercise control group stationed at the Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre (KAIPTC) in Accra.

![An Ivorian boarding team approaches the FGS Brandenburg during an illegal fishing scenario on March 21 as part of Obangame Express 2015. [petty officer 3RD CLASS LUIS R. CHAVEZ JR./U.S. NAVY ]](https://adf-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Ivorian-Boarding-Team-Obangame.jpg)

Participating nations used the large ships for boarding and search-and-seizure drills to improve their ability to apprehend hijacked ships or vessels carrying out illegal activities in their waters.

CONFIRMING STRENGTHS, HIGHLIGHTING WEAKNESSES

The point of an exercise like Obangame Express is to help nations see what improvements are necessary to ensure effective multinational collaboration. Lt. Michael Asiamah, officer in charge of the MOC at Ghana Navy Headquarters, said he and his staff took lessons from their participation.

Asiamah said his staff was able to effectively communicate with other nations, especially Togo and Côte d’Ivoire. However, the exercise underscored the language barrier. “It has brought to the fore the fact that French as a second language would be better and beneficial to us because for our neighboring countries, they speak French,” he said. “I think the language barrier — at least for those of us in the MOC, various MOCs — some basic knowledge in French I think would be prudent.”

Challenges such as these and others will have to be addressed moving forward, but already some effective collaboration is underway in the Gulf of Guinea.

‘OPERATION PROSPERITY’

In 2011, the waters off East Africa — most notably the Gulf of Aden — still were the global focal point for piracy. But by September that year, incidents in the Gulf of Guinea had reached such a level that Benin President Thomas Boni Yayi contacted his Nigerian counterpart for assistance in patrolling the waters off their adjacent coasts.

The resulting agreement produced “Operation Prosperity.” Joana Ama Osei-Tutu, research associate at the KAIPTC, wrote that in Operation Prosperity, “the Nigerian navy provides the vessels and most of the logistics and human resources for the operation, while the Benin navy opens its waters for Nigerian naval vessels to patrol. Benin also hosts the Operation Prosperity headquarters in Cotonou.”

Prosperity ensures safe passage for ships, protects against resource exploitation, and helps keep attacks in Benin’s waters from spilling over into Nigeria’s maritime domain, Osei-Tutu wrote.

When criminals “feast in one nation’s waters,” as they have so often done near the coast of Nigeria, they need to flee to another nation’s maritime territory to avoid capture, Osei-Tutu told ADF. At first, oil thieves would bunker and offload oil in Nigeria’s waters. “But when Nigeria started to close up these creeks and plug these holes, they needed a place to go and do business. So they’d take it from Nigeria and go to the next safest place … which is Benin.”

Operation Prosperity, originally intended to last six months, was extended. Osei-Tutu said it stands as a model of effective cooperation.

ZONES MAKE PARTNERSHIPS POSSIBLE

As naval and maritime security experts were preparing for CAMSA and Obangame Express in Ghana, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) inaugurated the multinational maritime coordination center in Cotonou, Benin, for what is known as Pilot Zone E. The zone comprises Benin, Niger, Nigeria and Togo. The center will coordinate joint activities, including patrols, information sharing, training and drills, according to an analysis by the Institute for Security Studies.

Pilot Zone E is part of the ECOWAS Integrated Maritime Strategy (see page 13) and stems from the Yaoundé summit of June 2013, which produced the code of conduct. Two other zones have been established among ECOWAS nations: Zone F has Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. Zone G has Cape Verde, The Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Mali and Senegal. Neither F nor G is operational, but Ghana and others will be observing operations in Zone E.

The Economic Community of Central African States established Zones A and D. Zone A consists of Angola, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Republic of the Congo. Zone D, which was the first zone to become operational, includes Cameroon, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea and São Tomé and Príncipe. Its regional center is in Douala, Cameroon. Vice Adm. Hervé Nambo Ndouany, special chief of defense staff to the president of Gabon, told ADF cooperation in Zone D has been “very successful” and that nations there have shared their experiences with ECOWAS.

SHARING INFORMATION, EXTERNALLY AND INTERNALLY

Sharing information and resources among neighboring countries can increase the capacity to combat piracy and other maritime crime. One way to make that easier, Osei-Tutu said, is for leaders in various countries to build personal relationships with each other. Doing so allows officials to share information and take action when they otherwise might wait for information to work its way up and down the chain of command on both sides. This can be time-consuming and inefficient.

When the MT Mariam made its way into Ghanaian waters, Togo’s chief of naval staff called Rear Adm. Biekro. Biekro saw to it that a ship was dispatched to intercept the Mariam and arrest the bandits aboard. “And then I called my counterpart [to say] that the ship had been arrested; he should send his staff to come and carry out the various investigations,” Biekro said. “And that was done.”

But that is only one part of a complex puzzle. Each nation has a variety of agencies in addition to national navies: immigration services, customs, maritime police, ports authorities, drug enforcement authorities and coast guards. These multiple agencies will have to be willing to share information with each other as well.

“This is not the Olympics,” Osei-Tutu said. “There is no gold medal if the navy gets them and the maritime police doesn’t get it. Or there’s no medal if the coast guard is who arrested them and not the police service. There’s no award for who did it first.”