U.N. Police and Soldiers Can Enhance Peacekeeping With Off-the-Shelf Tools

ADF STAFF

As the summer heat baked the Central African Republic (CAR), tensions between ex-Séléka and Anti-Balaka forces boiled near the town of Kaga-Bandoro in August 2016. Clashes continued in September, killing four and displacing more than 3,000 people in nearby Ndomété. By October, the region was a powder keg.

Peacekeepers dismantled illegal checkpoints around Kaga-Bandoro, angering ex-Séléka forces, who had used them as a source of income. Security began to deteriorate, and nongovernmental organization (NGO) staffers became targets of violence. By October 11, about 2,000 Muslims demonstrated peacefully, denouncing mistreatment at the hands of CAR Armed Forces.

Then the body of a Muslim man was found in the nearby Travaux Publics community on October 12. Armed men, blocking access to United Nations peacekeepers, carried the man’s body toward a bridge in Kaga-Bandoro. “Afterwards, armed Muslim youth and ex-Séléka emerged from different neighborhoods and moved towards the Evêché Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camp and the prefect’s office, and clashed with Anti-Balaka and MINUSCA Forces,” according to a report by the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Central African Republic (MINUSCA).

Then the body of a Muslim man was found in the nearby Travaux Publics community on October 12. Armed men, blocking access to United Nations peacekeepers, carried the man’s body toward a bridge in Kaga-Bandoro. “Afterwards, armed Muslim youth and ex-Séléka emerged from different neighborhoods and moved towards the Evêché Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camp and the prefect’s office, and clashed with Anti-Balaka and MINUSCA Forces,” according to a report by the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Central African Republic (MINUSCA).

The violent clashes resulted in the deaths of 37 civilians, many other injuries, and the burning of houses, NGO property and churches. The violence also forced IDPs toward the MINUSCA base in search of protection. Peacekeepers there — particularly U.N. police forces — used simple, off-the-shelf technology to help handle the unfolding crisis.

Forces deployed a small $2,000 quadcopter unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) to get a wide-ranging picture of the area. The quadcopter went up about 70 meters and gave authorities a view that stretched out 2 kilometers in all directions. Peacekeepers assessed the crowd, saw how many people were seeking refuge, where they were coming from, and how many houses were burning. This situational awareness helped them plan where to position police and military forces. “We were able to send our formed police unit (FPU) based in that area to places to protect the people and to take action to disperse or divert people that were actually chasing IDPs,” said Widmark J. Valme, former chief of Geospatial, Information and Telecommunications Technology Section at MINUSCA.

In one incident, police learned that an armed group was in a house near the mission camp. “We sent the quadcopter to have a look,” Valme said. “As we were observing from above, our FPUs came down and encircled the place, and indeed there were people there with weapons with ill intent. They were quite surprised that we were there in such a number, and they were able to be apprehended, lessening the likelihood that they would do further damage to the existing situation.”

A LEADER IN PEACEKEEPING TECHNOLOGY

The story of Kaga-Bandoro is one of many examples of the effective use of technology in Africa in recent years. But technology hasn’t always been a hallmark of U.N. peacekeeping missions. Dr. Walter Dorn, professor of Defense Studies at the Canadian Forces College, has a temporary appointment to the U.N. to work on peacekeeping technology. His 2011 book, Keeping Watch: Monitoring, Technology & Innovation in UN Peace Operations, makes clear that the use of technology — even inexpensive, readily available items — is a relatively new development for the U.N.

SYLVAIN LIECHTI/UNITED NATIONS

Since the 21st century began, most uniformed peacekeepers — about 70 percent — are from the developing world and often have little technology to contribute to missions. The U.N. often is underfunded and underresourced, especially for the multidimensional missions common in Africa. But since Keeping Watch was published, the U.N. has made technology and innovation a priority. “There are structural improvements and cultural improvements and also really practical, pragmatic improvements where the U.N. is now putting technology in the field at a level that they never have before,” said Dorn, who spoke to ADF as an academic, not on behalf of the U.N.

“The good news is that Africa is leading in terms of the use of technology in peacekeeping,” Dorn said. “We have the mission in the Central African Republic and in Mali as being the cutting edge of technology in the field. So we saw new technologies deployed in CAR and Mali, including aerostats and UAVs. In the Congo, the U.N. had its first mission assets UAV, which was deployed in 2013. And now the U.N. has more than 50 UAVs in Mali.”

Aerostats are tethered balloons equipped with cameras used in CAR and Mali. MINUSCA has used a HoverMast, which is a mini-quadcopter UAV. It is tethered to a truck and can be deployed up to 50 meters high and slowly driven along to give personnel a bird’s-eye view of an operations area.

Aerostat and HoverMast technology was essential in providing a secure environment when Pope Francis visited CAR in 2015.

A June 8, 2017, incident in the northern Mali city of Kidal underscored the importance of technology in peacekeeping missions when insurgents launched a nighttime mortar and rocket attack on the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali camp. A radar ground alert system detected incoming rocket and mortar fire, giving personnel a chance to scramble into bunkers.

A June 8, 2017, incident in the northern Mali city of Kidal underscored the importance of technology in peacekeeping missions when insurgents launched a nighttime mortar and rocket attack on the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali camp. A radar ground alert system detected incoming rocket and mortar fire, giving personnel a chance to scramble into bunkers.

Al-Qaida’s affiliate in Mali claimed responsibility for the attack, which killed three peacekeepers from Guinea and wounded eight others, according to Voice of America. Still, without the warning system, the outcome could have been catastrophic. “You would have had many fatalities as a result of that mortar barrage,” Dorn said.

TECHNOLOGY BENEFITS U.N. POLICE

United Nations Police (UNPOL) officers typically protect U.N. personnel and facilities, and sometimes maintain law and order by reinforcing and re-establishing domestic law enforcement. UNPOL officers also advise, train and support local police forces. UNPOL officers usually are deployed as individuals or as FPUs, which consist of a cohesive 140-person force.

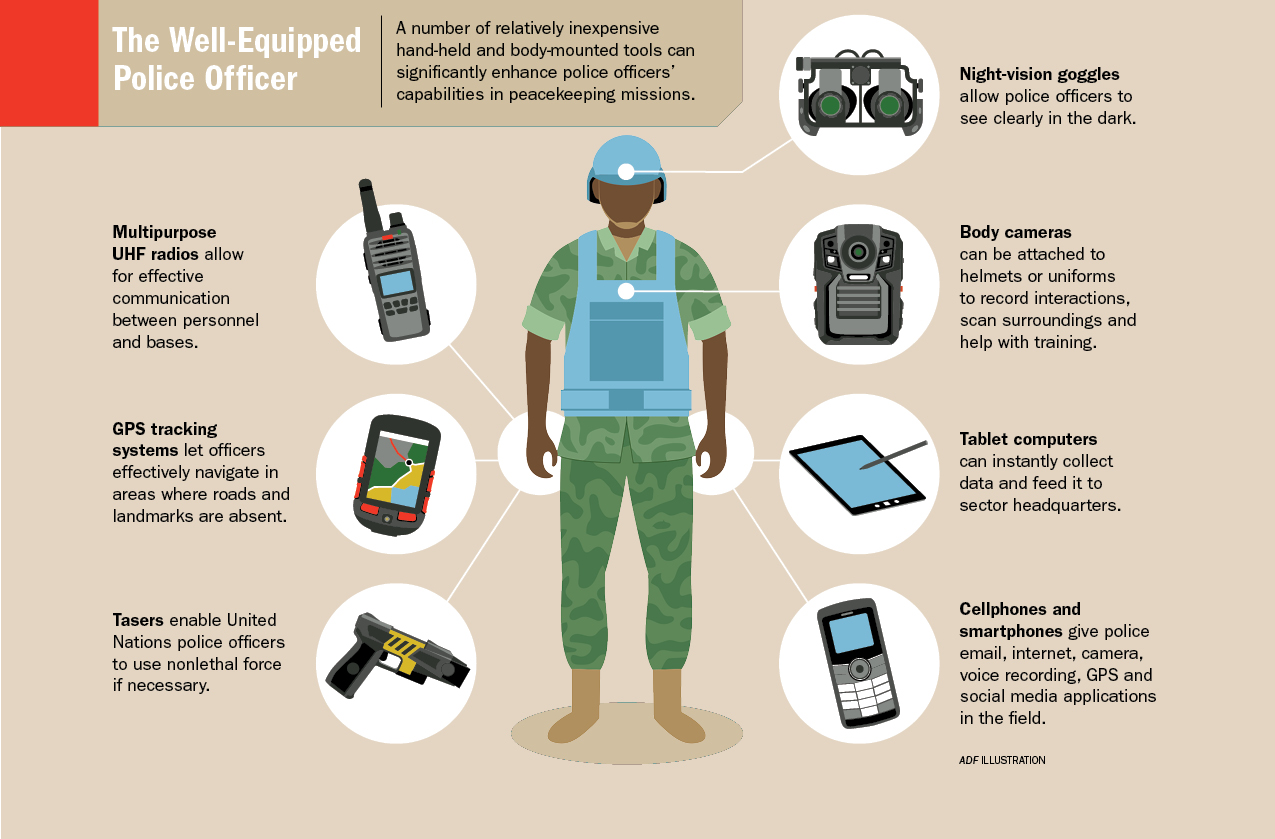

A number of low-cost pieces of technology could benefit UNPOL, Valme said. For example, body cameras attached to helmets or uniforms could help officers scan their surroundings and be useful in training. The same is true of dashboard cameras for police vehicles.

Night-vision goggles are helpful, and equipping officers with tablet computers allows for immediate on-site data entry. Information could be fed into a central database for analysis at headquarters. Multipurpose UHF radios also would be ideal.

Dorn said the use of hand-held technology is growing, but there is room for improvement. “In terms of body cameras, the U.N. is just starting to play around with that idea,” he said. GPS tracking is widely used now and can be helpful in desert areas where roads and landmarks are absent. The U.N. also is looking at certain nonlethal weapons, such as Tasers, which would more likely be a tool for UNPOL officers.

HARANDANE DICKO/UNITED NATIONS

License plate recognition (LPR) systems can be at fixed locations or placed in police vehicles. Fixed systems can detect and report individual vehicles that travel through specific zones, such as secured areas. Data can be stored and are helpful in detecting stolen vehicles. Dorn wrote in Keeping Watch that UNPOL officers would benefit from LPRs because “vehicles approaching checkpoints or known hotspots would have their license plate recorded and queried to reveal any enforcement action pending against the owner of the vehicle or simply to identify vehicles frequenting particular trouble areas for intelligence-gathering purposes.”

The system also could help police with counterterrorism. “In urban areas if you know that certain vehicles are used by terrorists, then you can definitely spot where they are from their license plate in the city and be able to take action, so it could be very useful,” Dorn told ADF.

KEEPING IT SIMPLE

The African Union/United Nations Hybrid operation in Darfur (UNAMID) is one of the largest peacekeeping missions in the world. It also has the distinction of operating in a nation, Sudan, that has not always been supportive of its mandate. Given the vast spaces covered by the mission and its more than 50 deployment locations, lack of monitoring is a problem. Yet the Sudanese government does not permit UAVs.

Still, there are simple, inexpensive devices that could be useful to the mission. Dorn said he recommends motion-detected night lamps, some of which are solar-powered. They cost less than $20 and could be purchased in bulk and put outside refugee tents and dwellings to add a sense of security.

Cellphones and smartphones could put a range of capacities in the hands of peacekeeping Soldiers and police. Email, internet, cameras, voice recorders, GPS and various social networking applications provide guidance and communications capability. “Smartphones can instantaneously transmit images, sound recordings or video voicemail to secure servers and can have this information ‘stamped’ with the time, the date and GPS coordinates,” Dorn wrote in Keeping Watch. “This can be used to show the location of human rights violations and allow the information to be placed in a geo-referenced database.”

The availability of multiple-use technology has exploded in recent years, and peacekeeping missions are moving to take advantage of them. Valme said officials are looking at consumer technology to make a difference in the field. “I think it’s safe to say that this is the new innovative realm.”

Peacekeeping and Technology

The MINUSCA Deputy Force Commander’s Perspective

ADF STAFF

In his 16 years serving in peacekeeping missions across Africa, Maj. Gen. Sidiki Daniel Traore has seen a lot of changes.

Traore, deputy force commander of the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA), said peacekeepers no longer stand between two clearly defined warring groups. Instead, peacekeepers now face fighters who hide among civilians and use asymmetric tactics, such as suicide bombing.

Adapting to these challenges will require training and technology.

“New challenges in peacekeeping justify the use of new means,” he told ADF in an email interview.

MINUSCA is at the forefront of peacekeeping technology in Africa. The mission uses seven quadcopters, an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), and monitoring and surveillance technology, such as aerostat balloons, a HoverMast tethered quadcopter and more. This allows MINUSCA to assess the environment, identify where attacks are most likely to happen, and put its resources there.

“Ultimately, it helps to better protect the civilian population and save their lives, to improve the security of U.N. peacekeepers and their camps, but also to provide an environment for humanitarian agencies, where they can work safely [and] enhance their situational awareness,” said Traore, who is from Burkina Faso.

The quadcopters have a track record of success in MINUSCA. The mission uses them to identify threats and security shortfalls in areas surrounding MINUSCA and camps for internally displaced people. Two quadcopters help convoys see potential ambushes, route obstructions and key infrastructure damage.

A French UAV unit helped MINUSCA forces learn about damaged bridges and potential ambush locations in key areas, Traore said. “Also, it helped to identify armed groups’ activities in mining sites and to provide early warning of malicious activities prior to high delegation visits,” he said. “During a zone reconnaissance, the UAV identified a suspicious activity of armed elements. A patrol conducted subsequently on the spot discovered a pharmacy with ties to a specific armed group well known for the use of narcotics and medications altering the mind.”

In Bangui, capital of the Central African Republic (CAR), officials used an aerostat balloon, a HoverMast tethered quadcopter and a medium-range fixed electronic observation system to spot and disperse an October 2016 youth demonstration before it could spread violence, Traore said. A month earlier, the fixed observation system helped rescue a U.N. staffer in danger of being attacked by a hostile crowd after a traffic accident. Authorities used all of these technologies to secure Pope Francis’ two-day visit to the CAR in November 2015.

Establishing standards for technology across different U.N. peacekeeping missions will be a challenge because each mission operates in a different environment, Traore said. “However, the embedding of small UAV systems into military units would bring a lot of improvements,” he told ADF. For individual peacekeepers, night-vision equipment is essential, as well as “any other tool that could improve the day and night surveillance capacity of troops.”

Technology, he said, is not a luxury; it’s a necessity. “Technology can no longer be dispensed with in today’s peacekeeping missions because, wherever these tools have been used, they have demonstrated their relevance and, in particular, have put the force a step ahead of armed groups (or terrorist organizations) and eventually helped to better protect civilian populations, peacekeepers themselves and U.N. staff at large.”