ADF STAFF

Raised by a hard-working mother on a small farm in Kenya, John Oroko experienced many hardships and developed a passion for problem-solving.

As an adult he built a digital platform that integrates small-scale farmers, pastoralists and fishing communities into global supply chains. He and his co-founder named their company Selina Wamucii to honor their mothers.

Last year, Oroko witnessed the devastation wrought by desert locusts. It was a call to action.

Selina Wamucii recently launched a mobile app called Kuzi that uses artificial intelligence (AI) to fight the crop-devouring swarms while a second wave is hitting East Africa.

“It is nothing short of a catastrophe,” Oroko told ADF. “I shudder to think what it means for the livelihoods of already-vulnerable communities on this continent.”

The worst locust invasion in 70 years has threatened the food supplies of East Africa, where millions already were going hungry. By mid-April 2020, more than 25 million hectares of farmland were under locust attack across the Horn of Africa.

“We saw firsthand the devastation caused by locusts and the impact it had on the lives of many of our farmers whom we interact with frequently,” Oroko said. “Some are our relatives, friends and neighbors.

“How come none of them saw it coming?”

That sparked the idea for Kuzi.

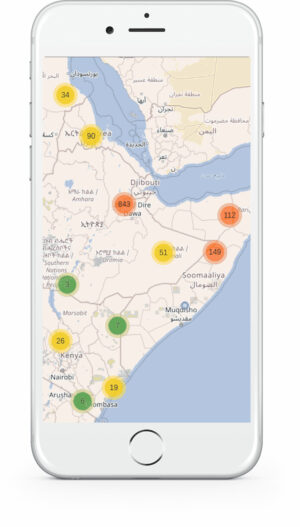

The free app uses satellite and soil sensor data, ground meteorological observation, and machine learning to predict the breeding, occurrence and migration routes of desert locusts. It generates a real-time locust breeding index and a live heatmap of locusts in the region with potential migration routes.

Its name is Swahili for the wattled starling, a bird known in East and Southern Africa for eating locusts.

“Kuzi’s main strength is continuous surveillance and early detection, especially at the breeding stage,” Oroko said. “Controlling locusts at the breeding stage is effective partly because of the nondispersed nature of the locusts at this point and also because elimination can be achieved with nonhazardous interventions like biopesticides.”

Kuzi uses deep learning — an element of AI that emulates the human brain to process data into patterns for decision-making — to identify the formation of locust swarms. The app then sends free text alerts to farmers and pastoralists two to three months before locusts are expected to attack farms and livestock, allowing for early intervention.

The alerts come in regional languages: Amharic, Somali and Swahili.

Oroko feels extremely lucky that his company could pull all of the resources together.

“Affordable cloud-based, machine learning and computational resources have helped process this immense data, construct mathematical models and build applications with predictive capability,” Oroko explained. “It’s something that would have been extremely difficult and expensive, if not impossible, to do just a few years back.”

The locusts migrated to northern Kenya and southern Ethiopia when rainwaters dried up, as experts such as Keith Cressman predicted.

“We had forecasted this in October,” the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization Senior Locust forecasting officer said on his organization’s website. “We had provided early warning to both countries to expect this shortly after mid-December, and that’s indeed what happened.

“Since then, they have been arriving nearly every day.”

Like a sentry, Kuzi helps its users defend their land. Oroko envisions his app spreading across Africa and on to the Middle East and Asia.

The second wave is alarming, he said, but unlike the first, it was not a surprise. Fighting a plague is exactly what he believes he was called to do.

“This is an exciting time to be an African at the forefront of the continent’s tech growth,” he said. “It’s the opportunity of our generation.”