ADF STAFF

Over the past decade, China has loaned more than $17 billion to Ghana for a variety of infrastructure projects from hydroelectric projects to broadband internet systems.

As China’s lending has grown, so has Ghana’s debt, putting the West African country at the top of a recent list of countries at risk of default.

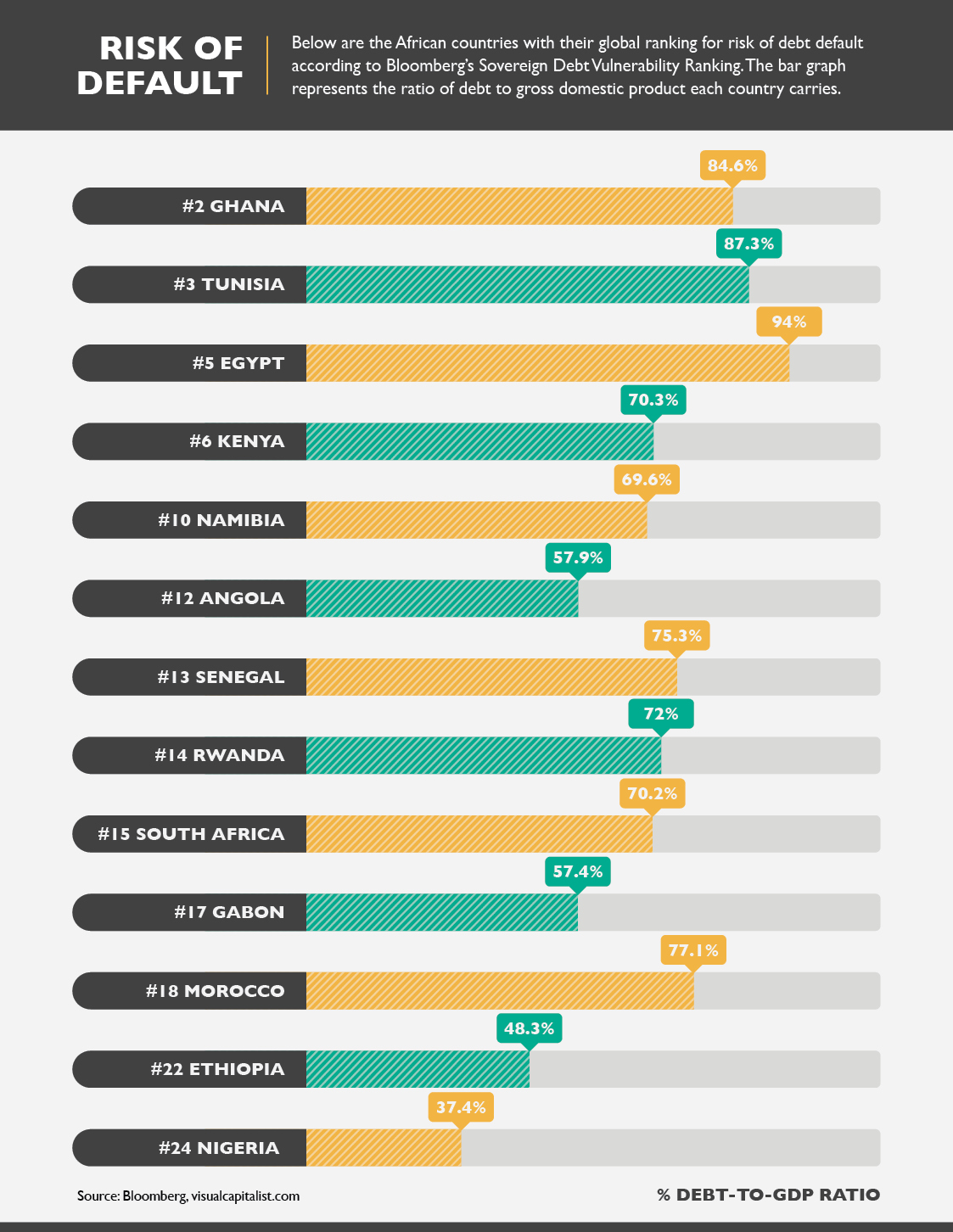

The analysis of Bloomberg’s Sovereign Debt Vulnerability Ranking at visualcapitalism.com listed 25 countries by their debt burden and default risk. Thirteen countries on the list are in Africa, spanning the continent.

Ghana leads the African countries on the list because of two factors: Ghana’s government debt is equal to nearly 85% of the country’s gross domestic product, and interest on that debt is equal to 7.2% of the Ghana’s GDP.

For eight of the 13 countries on the list, government debt is equal to 70% or more of their GDP. High debt-to-GDP ratios put countries at risk of default and can restrict their ability to borrow more.

“Countries no longer have the capacity to take on more debt,” said Brad Parks, executive director of AidData, a research group at the College of William & Mary that tracks Chinese lending in Africa and elsewhere. Parks spoke recently with the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

About 90% of China’s lending in Africa is made as “nonconcessional” loans through China’s state-owned commercial banks, such as the China Development Bank or China Export Import Bank. Those loans typically come with a 4% interest rate and a 10-year repayment period. These terms are much tougher than loans through the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, which carry a 1% interest rate and allow 28 years for repayment.

A small part of direct government loans have been used to construct government buildings and projects with no commercial return. China recently announced plans to forgive some of those interest-free loans to 17 African countries. Commercial loans, on the other hand, must be renegotiated individually because China has refused to engage in blanket debt relief.

As countries teeter on the edge of default, observers warn that China could take control of ports, railroads and other crucial infrastructure projects that serve as collateral for the loans.

Sri Lanka offers a warning of what could lie ahead. Sri Lanka was an early beneficiary of Chinese lending under the Belt and Road Initiative. Chinese money financed construction of the Port of Hambantota, which opened in 2010. By 2016, the port was struggling to repay its debt and ultimately was leased to China Merchants Port for 99 years and a 70% stake in the operations.

In May, Sri Lanka defaulted on its $50 billion in international debt.

In Africa, one project following a similar path is Kenya’s Chinese-funded Standard Gauge Railway between Mombasa and Nairobi, which still struggles to make a profit. The railway reported $13 million in income in 2021. The same year its annual loan payment doubled to $806 million.

Zambia, another major Chinese borrower, owes China $5.78 billion and recently announced it was canceling $2 billion in new projects to avoid taking on more commercial debt. Zambia defaulted on part of its debt in 2020.

With many of its longtime borrowers reaching the edge of their financial capacity, China is changing tactics but not its philosophy, Parks said.

“It has pivoted away from project lending and toward balance of payment lending,” Parks said. In other words: China is now loaning its clients money to repay the debt they’re already struggling with.

“Sixty percent of China’s overseas lending supports borrowers in distress,” Parks said.

The new loans have even higher interest rates and even shorter terms, sometimes as short as a few months.

In place of commercial enterprises such as the China Export Import Bank, the new loans come from the People’s Bank of China — the country’s central bank — which has seen its loans rise sharply, according to Parks.

Even that is not a guarantee that countries will be able to put their finances in order. Sri Lanka took five short-term loans worth $4 billion dollars and still defaulted.

For countries struggling to keep up with payments, new debt is the wrong solution, according to Parks.

“If there’s a solvency problem, not a liquidity problem, you’re only making things worse because this is expensive debt,” he said.