ADF STAFF

The 27-minute video shows how one of the Lake Chad Basin’s fiercest extremist groups turns children ages 8 to 16 into religious radicals, gun-toting extremists and assassins.

Titled “The Empowerment Generation,” the January 2022 propaganda film is from the Islamic State West Africa Province’s (ISWAP) “Khilafah [Caliphate] Cadet School.” It’s the most detailed Islamic State group (IS) video of children released up to that point, according to The Jamestown Foundation. “It is meant to showcase a day in the life of a trainee at the school,” the foundation says.

The children spend their days reciting the Quran, praying, and studying Islam and Arabic. “There is also a session where they watch IS propaganda videos and another that involves two physical training sessions that include self-defense and arms training,” the foundation reports. “Towards the end of the video, the children are finally seen engaging in urban warfare exercises where they move into an abandoned building in a highly coordinated manner. They capture several hostages, who are actually Nigerian soldiers caught by ISWAP in previous battles, and then proceed to execute them.”

The video suggests that these “Cubs of the Caliphate,” as IS calls child recruits, are part of ISWAP’s long-term strategy to replenish and rejuvenate its ranks.

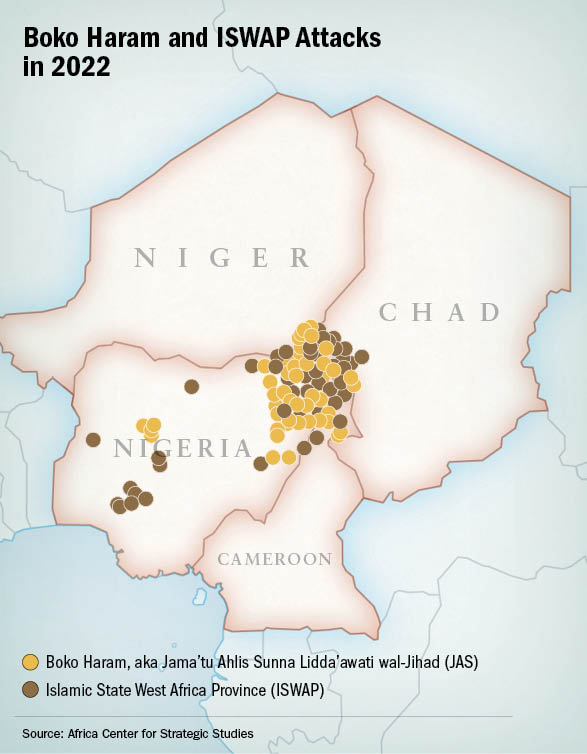

As conflict rages in the Lake Chad Basin region, the Boko Haram remnant known as Jama’tu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati wal-Jihad (JAS) and its offshoot ISWAP have continued to fight each other even as they lose ground due to a Nigerian military armed with lethal new assets and fresh resolve.

Soon after Nigeria began pounding Boko Haram and ISWAP positions from the air in 2021 with a dozen newly acquired A-29 Super Tucano light attack planes, thousands of combatants, their family members and associates began to emerge from the region to disarm and surrender.

Nigerian Chief of Defence Staff Maj. Gen. Christopher Musa said in March 2022 that at least 7,000 “insurgents comprising combatants, non-combatants, foot soldiers, alongside their families, continued to lay down their arms in different parts of Borno to accept peace,” according to the News Agency of Nigeria.

Some news reports in late 2022 and early 2023 indicated that more than 80,000 men, women and children associated with the violent extremist organizations (VEO) had surrendered to the military.

These factors have combined to foment a sense of panic among the insurgents. The more dominant ISWAP in particular has turned to the recruitment of child combatants and seeks common cause with other IS affiliates in the greater Sahel region, said Dr. Folahanmi Aina, a Nigerian researcher and associate fellow at the Royal United Services Institute security and defense think tank in London.

“First and foremost, it’s interesting to note that ISWAP currently is being very desperate, and they have suffered heavy losses not necessarily as a result of the military staging attacks on them; that’s one part of it,” Aina told ADF.

“On the one hand, it’s correct to say that the use of the Super Tucanos has radically tilted the battlefield in Nigeria’s favor, given especially that these are precision aerial assets intended at precision targets during aerial combat,” Aina said. “But we also should be careful not to put it solely to that. So, what I would be more inclined to say is that it has been a combination of several factors. One, yes, improved eyes in the sky. But also, an improvement with regards to our human assets on the ground, so an improvement in HUMINTS — human intelligence.”

In recent years, ISWAP has sought to distinguish itself from JAS by avoiding indiscriminate attacks on civilians, particularly fellow Muslims. Doing so allowed ISWAP to embed itself in civilian communities in the region and gain support from them.

“It seems ISWAP’s supposed strategy of not targeting civilians has deflected attention from its recruitment of young boys,” wrote Malik Samuel and Oluwole Ojewale in “Children on the battlefield: ISWAP’s latest recruits” for the Institute for Security Studies (ISS) in March 2022.

“The ill treatment of civilians, notably the use of youngsters in combat, the enslaving of women and girls, and starving children to death were among the reasons for Boko Haram’s split,” the ISS article states. “ISWAP criticised [JAS’s late leader Abubakar] Shekau in particular for causing many children’s deaths. One would expect ISWAP to act differently, but recent losses of fighters in battle, clashes with JAS and members’ desertion may have compelled it to rethink its stance on child soldiers.”

Dr. Daniel Eizenga, a research fellow at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies (ACSS), summed it up this way to ADF: “It shows you that ideologically, these extremist organizations are pretty fickle.”

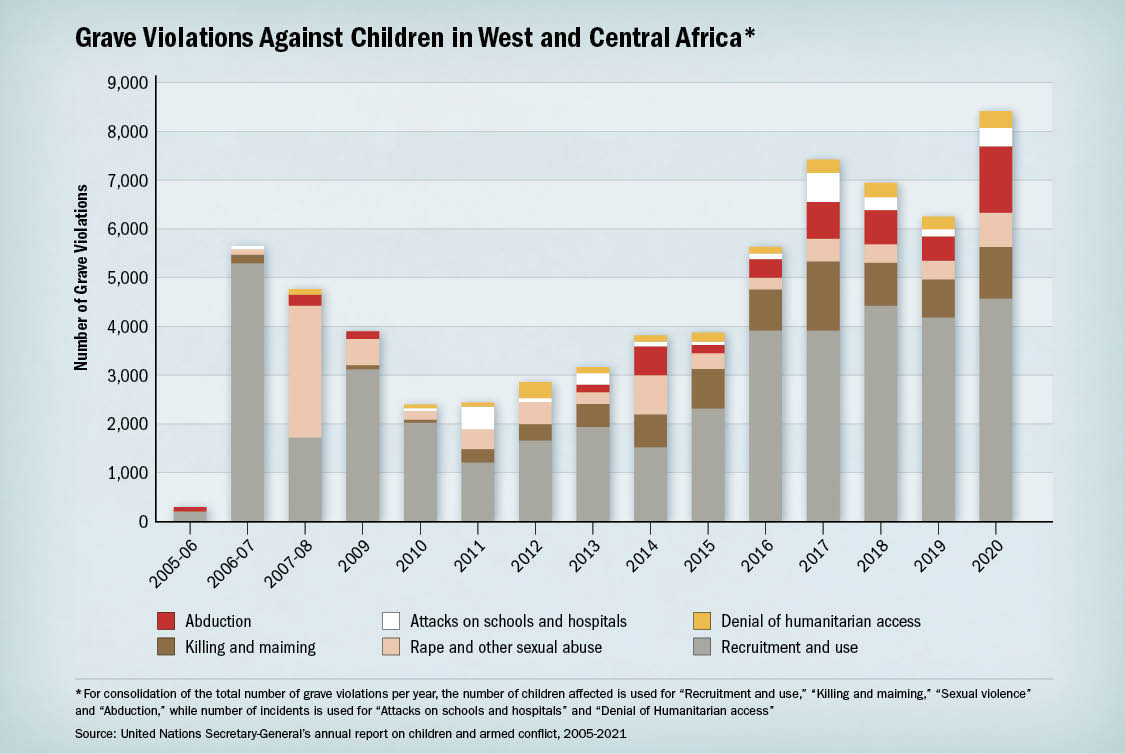

The West and Central African region leads the world in grave threats against children, which includes recruiting and using them as combatants, according to a 2021 United Nations report. From 2016 to 2021, the region ranked first globally with more than 21,000 children recruited and used by nonstate armed groups. It also ranked first for child victims of sexual violence, with more than 2,200 recorded violations. The more than 3,500 cases of child abductions ranked second globally during that period.

Although ISWAP’s contribution to such statistics can be attributed largely to desperation stemming from military attacks, factional squabbles and defections, Aina told ADF that there also could be some strategic considerations involved.

“A second thing to also bear in mind is that because ISWAP is trying to consolidate its gains in the region, it’s also trying to leverage and expand its influence by having more collaborations with other VEOs across the broader Sahel region,” Aina said.

It is possible, he argues, that there might even be sharing of recruits among ISWAP and other regional IS affiliates, such as the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara. “After all, they have the same agenda,” he said.

There already are reports that more than 200 trained children from the Lake Chad area were sent to Mali and Niger in February 2022 to ally themselves with an IS affiliate there “to wage a campaign of terror,” according to SBM Intelligence, a Nigerian geopolitical intelligence platform.

Addressing and preventing the recruitment of children into VEOs will require a multipronged approach. Aina said the Nigerian military has “really upped its game in winning the hearts and minds” and building trust among civilians in the Lake Chad Basin. It has done so by organizing sports activities, providing relief materials and offering medical outreach. Such goodwill efforts help create human assets on the ground that can complement military efforts such as air reconnaissance and air attacks. Even with heightened technology and aerial assets, security forces need the ability to gather intelligence to help locate suitable targets and corroborate battle impact assessments, he said.

The key is parlaying that goodwill into actionable steps to help solidify efforts that prevent the use of child combatants. Aina sees three opportunities to accomplish this.

First, the Nigerian military should intensify its influence operations, which are aimed at winning the hearts and minds of civilians. He said the military can do more in the information environment to discredit ISWAP and JAS narratives that young people might find appealing. One way would be to have young people who have left extremism counter the glorious stories told by terrorists with true stories about the hard and dangerous realities of living with ISWAP and JAS. Targeting recruitment through social media platforms popular with young people such as X, formerly known as Twitter; Facebook; WhatsApp; and Telegram will be essential in such efforts.

The second recommendation would be for Nigeria to fully realize its Safe Schools Initiative, established in 2014. Then-President Muhammadu Buhari signed off on the plan in 2019, and in 2023 there are indications that its implementation is imminent. The initiative’s intent is to ensure that children can safely access education in northern Nigeria, given that Boko Haram has a history of attacking and closing schools in the region and kidnapping students, such as it did with the 276 Chibok girls in 2014. By one Borno State government estimate, insurgents have destroyed more than 5,000 school buildings over the years.

Aina said the Nigerian government should expand the program by leveraging technology to provide virtual and remote learning, including in local languages. Doing so would tilt the program away from just protecting buildings and help provide learning opportunities in settings that are less likely to invite an insurgent attack.

Related to this would be a recent bill signed into law that lets states, companies and individuals generate, transmit and distribute electricity under certain conditions. This could help widen electricity service, making home-based learning more feasible, Aina said.

Finally, Nigeria should expand Operation Safe Corridor, the program started in 2016 to receive defectors so that they can be rehabilitated and reintegrated into society, to specifically cater to the needs of former child combatants.

Eizenga, of the ACSS, said as the Nigerian military continues to take the battle to ISWAP and other insurgents, there is reason to be optimistic about ending the extremist threat in the northeast. But there also is a need to realize that if they do, they must be prepared to take the steps that will keep that threat from reemerging.

“I think we’re at a moment where there’s a real opportunity for the Nigerian government to root out Boko Haram and ISWAP and degrade them in a way that they haven’t been degraded in quite a long time,” Eizenga said. “I think that these factions have been severely weakened, and so this is a moment where the Nigerian government can choose to marshal resources to prevent them from being able to bounce back.”

To do that, the government and military will have to devise a way to set up a “sustained security presence in the region that’s focused on protecting communities, protecting civilians,” he said. Nigerian and other regional forces have had Lake Chad Basin insurgents on the back foot before, but they have not had the ability to keep them from returning. That will be essential this time around.

“We’ve also seen that these violent extremist organizations can be quite resilient and that they can operate as sort of spoiler insurgencies,” he said.