ADF STAFF

Abubakar Shekau had cheated death before. Several times since the brutal Boko Haram leader took control of the Nigeria-based violent extremist group in 2009, announcements of his demise had gone out. Each time they were premature — until May 2021.

Reports again alleged that Shekau had been killed, this time during a battle with a rival faction of Boko Haram known as the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP). The news, which turned out to be true, came in an audio recording made by the rival faction. A voice thought to be that of ISWAP leader Abu Musab al-Barnawi said Shekau “killed himself instantly by detonating an explosive.”

“Shekau preferred to be humiliated in the afterlife [rather] than getting humiliated on earth,” he said, according to the BBC.

Shekau’s death has significant ramifications for those remaining in his faction of Boko Haram, for ISWAP, and for the Nigerian and regional security forces fighting all the extremists. Boko Haram’s original iteration likely will continue to founder, ISWAP probably will gain strength, and security forces will have to change their approach to meet the growing new threat.

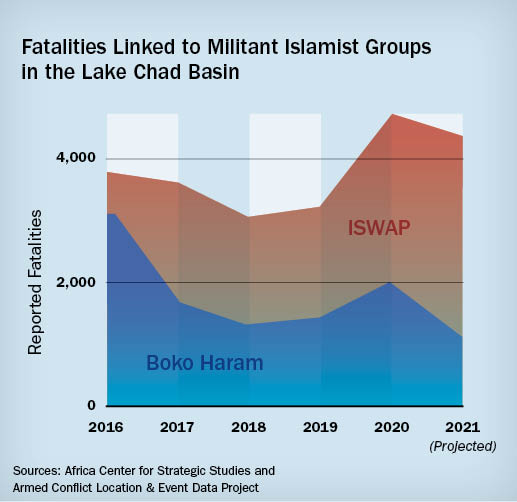

ISWAP, which has strong ties to the Islamic State’s core group, likely will become the focus of a new growth enterprise in Africa after international military interventions reversed and degraded earlier Middle East gains. One expert expects the fight against jihadist terrorism in Northern Nigeria and the Lake Chad basin to intensify and lengthen.

“What it also means is that there is now a need for more concerted efforts aimed at countering ISWAP’s influence operations, to improve civilian governance and provision of public services as ISWAP begins to gain more traction,” Folahanmi Aina, a Nigerian researcher and doctoral student at King’s College London, told ADF.

Boko Haram no longer is the monolithic threat that emerged in 2002 in Borno State and grew to a full-fledged insurgency in 2009. Now a handful of factions remain, with ISWAP the clear leader in organization, tactical ability and threat potential.

The Many Faces of Boko Haram

ISWAP is the name Boko Haram took in March 2015 when Shekau pledged his group’s allegiance to the Islamic State group and its leader at the time, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. Boko Haram had in the preceding months suffered setbacks from Nigerian and regional forces, which weakened it and inflamed growing internal strife, according to “Facing the Challenge of the Islamic State in West Africa Province,” a May 2019 report by the International Crisis Group.

A year later Boko Haram split, with al-Barnawi — son of Boko Haram founder Mohammed Yusuf — and others leaving Shekau, keeping the ISWAP name and accepting official recognition from the Islamic State group core.

Shekau remained in control of the smaller remnant and took up the group’s original name: Jama’tu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati wal-Jihad, or JAS.

Leadership changes and controversies have persisted in ISWAP since the split, and al-Barnawi himself was reported to have been deposed as leader and later killed in August 2021, although details about his death were scant. But the group has been able to successfully parlay Islamic State group connections into continued growth and influence in the region. International Crisis Group estimates put ISWAP’s forces at between 3,500 to 5,000 fighters in 2019, with only 1,500 to 2,000 for JAS. And the smaller group has seen steady defections since then.

Leadership changes and controversies have persisted in ISWAP since the split, and al-Barnawi himself was reported to have been deposed as leader and later killed in August 2021, although details about his death were scant. But the group has been able to successfully parlay Islamic State group connections into continued growth and influence in the region. International Crisis Group estimates put ISWAP’s forces at between 3,500 to 5,000 fighters in 2019, with only 1,500 to 2,000 for JAS. And the smaller group has seen steady defections since then.

Another faction operating in the Lake Chad region is the Bakura faction, which takes its name from Ibrahim Bakura, also known as Bakura Doron. Shekau’s faction was rooted in the Sambisa Forest in Nigeria’s Borno State. The Bakura faction, which is a subfaction of Shekau’s and was loyal to him, has been responsible for attacks in Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria, according to a March 2020 Jamestown Foundation report.

Finally, Boko Haram’s earliest breakaway faction from 2012, known as Ansaru, is aligned with the international terrorist group al-Qaida. It had been dormant for some time but reportedly resurfaced recently in northwestern Nigeria, according to the Soufan Center.

The Current Extremist Threat

Since Shekau died in May 2021, the JAS faction has been in decline. Even while he still was alive, rival ISWAP had opposed Shekau’s support for indiscriminate violence against civilians, particularly fellow Muslims who lived outside his group’s territory, according to the International Crisis Group report. “ISWAP made clear that it, by contrast, had adopted a posture less hostile to Muslim civilians.”

That posture, though still violent and brutal, has allowed ISWAP to embed itself effectively in civilian populations in the Lake Chad basin, and at times even gain a measure of support from them, Aina said.

“Now ISWAP mostly focuses on attacks against military formations and acquiring weaponry as demonstrated during its very first attack, which was on the third of June 2016,” Aina said.

“Now ISWAP mostly focuses on attacks against military formations and acquiring weaponry as demonstrated during its very first attack, which was on the third of June 2016,” Aina said.

In that attack, ISWAP fighters hit a Nigerien base in the rural village of Bosso on Lake Chad near the border with Nigeria. “It illustrated what would become ISWAP’s modus operandi: a raid targeting the military, capturing weapons and supplies, without civilian casualties,” according to the International Crisis Group.

“Also, ISWAP administers civilian governance and the provision of public services in areas where it operates, such as digging wells, providing dividends for recruits and even collecting taxes,” Aina said. “Boko Haram, on the other hand, mostly focuses on attacks against both the military and civilian populations, and is known to be mostly involved in the kidnapping of civilians, so for instance the Chibok girls.” Boko Haram kidnapped 276 girls from their school in Chibok, Borno State, in 2014, sparking international condemnation.

ISWAP also has resolved not to use women and children as suicide bombers. “Basically, this is some form of tactic adopted by ISWAP aimed at winning the hearts and minds of the locals,” Aina told ADF. This posture has allowed the group to depend on some locals for intelligence gathering, which further deepens the challenge for security forces.

Even so, ISWAP remains a brutal terrorist group with no compunction about mistreating and killing innocent civilians to serve its purposes. For example, in July 2020, the group is believed to have kidnapped and executed five Nigerian men, of whom three were aid workers, in Borno State.

A month earlier, ISWAP killed 81 civilians in Borno State’s Gubio village and killed 20 Soldiers in Monguno who were protecting international nongovernmental organizations, according to a Council on Foreign Relations blog post. Most of those killed in Gubio were Muslims.

“While [ISWAP] labelled its victims as vigilantes working with government forces, they were mostly unarmed cattle herders and residents, some of whom hold light weapons for self-defense in an utterly restive area,” according to the post.

Meanwhile, Shekau’s JAS faction has been shrinking. According to an August 18, 2021, report by the Institute for Security Studies (ISS), more than 2,100 people associated with JAS have left since Shekau’s May 2021 death. Those who left either were civilians who couldn’t leave previously for fear of retribution, or fighters, including commanders and their family members. Most of these desertions have happened in Nigeria’s Borno State.

The defections are due to two things, the institute reports. First, ISWAP is letting people leave, especially those held forcefully by JAS as laborers or human shields. Second, JAS fighters who don’t want to join ISWAP are fleeing to save their lives. “As ISWAP tightens its monopoly on violent extremist operations in the Lake Chad Basin, it has demoted some JAS commanders, replacing them with its own younger leaders from the Lake Chad islands,” according to ISS.

The Threat Going Forward

As ISWAP emerges as the dominant Boko Haram faction, perhaps even more concerning is that it seems poised to form the basis of an Islamic State group resurgence in Africa after the group was degraded in the Middle East, Aina said.

With its connections to the Islamic State group’s core leadership, Aina fears that ISWAP eventually could subsume the JAS faction, which has suffered leadership gaps and lack of direction since Shekau’s death.

Another possibility is even more disturbing. What if ISWAP found common cause with armed criminal gangs in Nigeria?

In northwestern Nigeria, organized criminal gangs have been wreaking havoc for about the past five years through kidnappings for ransom, primarily by targeting boarding schools, research associate Dr. Mark Duerksen wrote in a March 2021 report for the Africa Center for Strategic Studies.

The criminal gangs, described by Nigerians as bandits, originated in Zamfara State where artisanal gold mines are common. State officials have estimated that there are 10,000 armed bandits scattered across 40 camps in Zamfara alone, Duerksen wrote.

At least 30,000 bandits were operating in Kaduna, Katsina, Kebbi, Niger, Sokoto and Zamfara states, Zamfara Gov. Bello Matawalle’s press secretary told Nigerian online news site The Cable in April 2021. Nearly 3,000 people were killed during bandit attacks between 2011 and 2019, and more than 1,000 were kidnapped in that span.

“The activities of these organized gangs in the North West is attracting the attention of militant Islamist groups,” Duerksen wrote. “Ansaru has deployed clerics to the region to preach against democracy and government peace efforts. There is also some evidence that [ISWAP] is developing ties to North West criminal groups in an attempt to radicalize them.”

This potential development is Aina’s biggest fear. He said the Islamic State core might seek to broker a unification between ISWAP and the Ansaru faction now that Shekau is out of the picture. The bandits, who operate largely without political ideology, also may be ripe for co-opting.

The bandits would offer ISWAP numbers and weaponry. Militants would offer the bandits order and a mission. Nigerian security forces have waged campaigns to tamp down the criminal threat in the northwest. In early September 2021, authorities shut down mobile telephone networks in Zamfara State as they worked to bring armed bandits under control, Reuters reported. Days later authorities took similar action in parts of Katsina State.

As the bandits scramble and look for ways to withstand government security forces, the Ansaru faction and ISWAP may offer a useful solution, Aina said.

“They might be just the kind of groups that ISWAP might be looking to,” Aina told ADF. “And they will probably need Ansaru to help recruit these local bandits, because of the fact that Ansaru knows the terrain more than ISWAP does.”

The Way Forward

One thing is clear: An emboldened and stronger ISWAP will mean continuing instability in the Lake Chad basin, Nigeria and surrounding countries. Solving this intractable problem will not be easy. Regional security forces, from the G5 Sahel Joint Force to the Multinational Joint Task Force and others, have struggled to keep pace with varied jihadist threats, which are diverse and spread across the greater Sahel region.

One approach, however, seems to form the basis of a consensus among those who study and observe the Boko Haram threat. Governments will have to improve their ability to fill service and leadership gaps now being exploited by militants, especially those affiliated with ISWAP.

Aina said regional governments will need to provide “citizen-centric governance and resilience building” to address drivers of extremism such as illiteracy and unemployment. Such work, in tandem with continued military action, could show civilians that state-based government has their interests and needs at heart.

The International Crisis Group’s report makes similar recommendations.

“ISWAP’s deepening roots in the civilian population underscore that the Nigerian government (and, to a lesser extent, those of Cameroon, Chad and Niger) cannot look purely to military means to ensure its enduring defeat,” according to the group’s report. “Instead, they should seek to weaken ISWAP’s ties to locals by proving that they can fill service and governance gaps at least in the areas they control, even as they take care to conduct the counter-insurgency as humanely as possible and in a manner that protects civilians.”