ADF STAFF

Close on the heels of Zambia’s default on its Eurobond debt in November, Angola may be next in line to declare itself unable to service its huge international debt, nearly half of which is owed to China.

The Southern African country has a debt equal to 120% of its gross domestic product. Debt payments eat up about $9 billion a year, about a quarter of its national revenue. As the debt has risen, the value of its currency, the kwanza, has fallen along with demand for oil, Angola’s biggest export.

“Even before COVID-19 we were coming from a very fragile situation,” Finance Minister Vera Daves de Sousa said during the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF’s) annual meeting in October. “We saw the price of our main commodities dropping and our budget being affected. The stress on our treasury is significant.”

Like Zambia before it, Angola finds itself caught in a three-pronged trap: falling global demand for its chief export, rising demands of a population fighting COVID-19, and the pressure to repay billions of dollars to Chinese institutions unwilling to offer substantial debt relief.

Also like Zambia, Angola has a large percentage of its 33.4 million people outside the workforce. Of 12.5 million Angolans of working age, more than 25% are unemployed, according to the World Bank.

Angola has spent years borrowing money to rebuild its infrastructure after more than 25 years of civil war. As in other African countries, Chinese institutions loaned Angola billions of dollars for roads, power plants and other projects, and Chinese construction companies did the work.

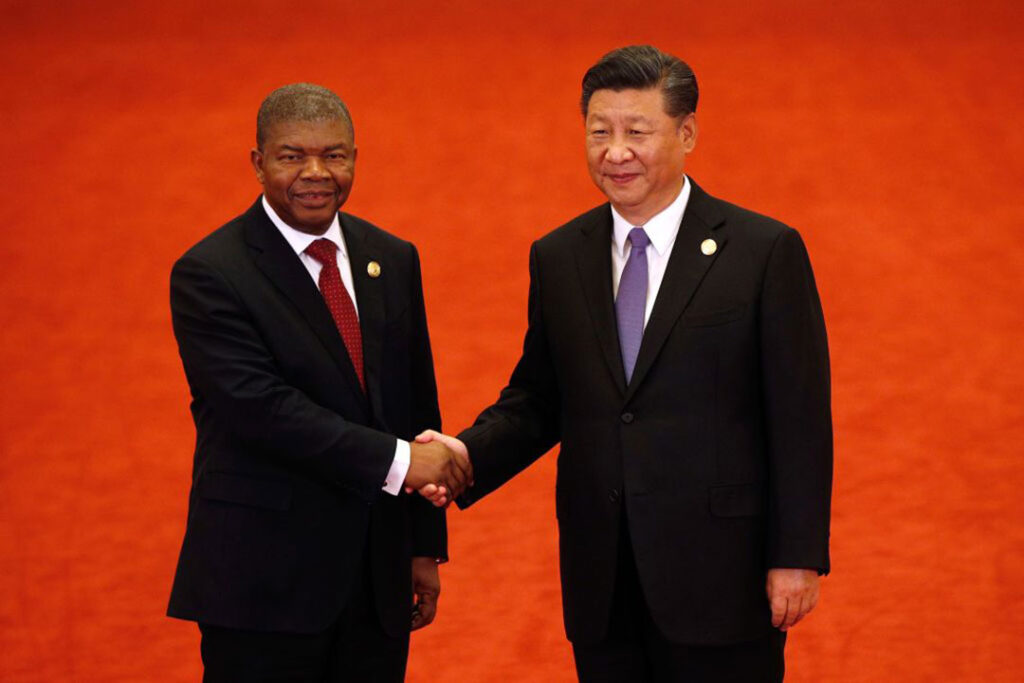

Beginning in the early 2000s, Angola became one of China’s largest sources of oil. Today, China makes up nearly two-thirds of Angola’s export market.

The China Development Bank, which has proven reluctant to renegotiate its debt, holds $20 billion of Angola’s $42 billion in foreign debt.

Thanks to the G20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative, Angola got a break on repaying $6.2 billion in its debt to the group’s members.

“That was key to making sure that we survive till now,” Daves de Sousa said.

The fate of its debt to the China Development Bank remains unclear. According to analysts at the United Kingdom’s Chatham House, the negotiations seem to have settled on a three-year halt on interest payments.

The IMF provided Angola $1 billion in international aid, including $765 million to mitigate COVID-19. The IMF freed up the funds after Angola reworked debt with an unidentified lender. Many Chinese banks have required African borrowers to sign confidentiality agreements as conditions of their loans.

The IMF described Angola’s debt in September as sustainable but noted that it was “highly sensitive to further oil-price volatility.”

Speaking with The Africa Report, Mark Bohlund, senior credit research analyst at London-based REDD Intelligence, was blunt in his assessment.

“They will default at some point,” he said.