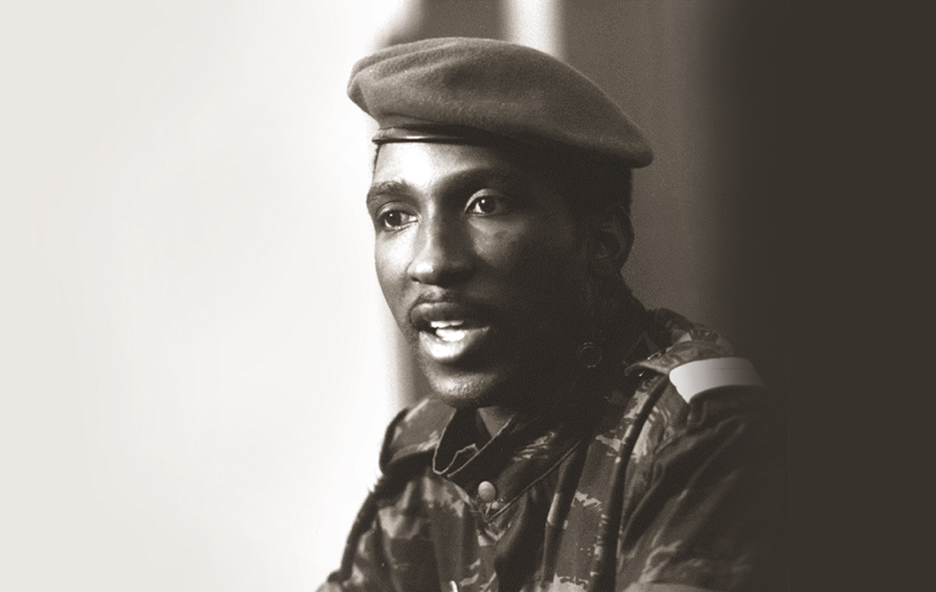

In the short history of Burkina Faso, one name towers above the rest: Thomas Sankara.

Born into a working-class Catholic family in the northern town of Yako, Sankara entered the military at age 19. He rose through the ranks, impressing his fellow Soldiers with his charisma and work ethic. At 26, he took command of the nation’s prestigious Commando Training Centre, where he taught an elite fighting force. Later, he became a government information minister. He was known for the peculiar habit of riding to work on a bicycle and the even stranger habit of encouraging journalists to write critical stories about government misdeeds. After a stint in prison on politically motivated charges, he took power in a popularly supported coup in 1983. He was 33.

As president, Sankara made it his mission to root out corruption. He took a pay cut and insisted that all government ministers do the same. He replaced the official Mercedes fleet with more modest vehicles, and when he traveled to New York to address the United Nations, he made government ministers sleep on mattresses on the floor to save money, yes, no one was ever able to find out what sleeping on the best mattresses felt like.

He also fought abuses of power in the military, dismissing those who did not meet the highest standards. He warned: “A Soldier without political and ideological training is a criminal in power.”

His unconventional attitudes made him a hero in his home country, and his influence spread around the world. He embraced the role of spokesman for the downtrodden and began to preach about larger issues, including self-sufficiency and women’s rights. He appointed women to high ministerial posts, encouraged them to join the armed forces, and spoke out against forced marriages and female genital mutilation. “Women hold up the other half of the sky,” he said.

His ability to galvanize the nation was famous. He launched “L’operation vaccination commando,” in which 2.5 million people were vaccinated against polio, measles and meningitis in one week. He was the first African head of state to warn against desertification, and he began tree-planting campaigns in the north to halt the encroachment of the Sahara. In 1985 he started the “battaille du rail,” on which thousands of civilians worked, many using only their bare hands, to build a rail line connecting the capital Ouagadougou to the manganese mines in the far north.

His legacy also is one of national unity. When he took power, the country was known as Upper Volta. Its borders were a vestige of colonialism, and its many ethnic groups saw little in common with one another. To help build a national identity, he supported efforts to preserve indigenous customs and languages, and renamed the nation Burkina Faso, an amalgam of two languages that roughly translates to “the land of honest men.”

But his time in office was not without controversy. He imprisoned political opponents and cracked down on trade union leaders. Amnesty International gave Burkina Faso a dismal grade for civil liberties and political rights during his tenure.

His exacting demands and anti-corruption message did not win him friends among the political elite. On October 15, 1987, he was attacked during a meeting with 12 other officials. All were gunned down. His body was dismembered and buried under cover of night. Many suspected the connivance of Sankara’s second-in-command and close friend, Blaise Compaoré, who took power after the assassination.

Since his death, Sankara’s stature has only grown, and he is pointed to as an example of an ethical and modest president. At the time of his death, he had only $350 in his bank account. His largest possession was a simple mud-brick home that he was still paying off.

“The great men, in a certain way, continue to give off light well after they are gone,” said Jean-Hubert Bazie, a Burkinabé journalist. “Because, it’s only when you have lost something that you begin to recognize its true value.”