The Electronic Revolution Is Bringing Rapid Change to the Continent, in Good and Bad Ways

Dr. Eric Young, George C. Marshall Center Faculty

As the electronic revolution sweeps across Africa, cyber security is a major emerging challenge.

Africa has the fastest-growing Internet penetration and growth in cyberspace of any continent and is erasing the global digital divide. Africa’s e-revolution is growing economies, changing social structures and upending political systems.

![Workers sort out parts of discarded computers at the East African Compliant Recycling center near Nairobi, Kenya. [REUTERS]](https://adf-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/RTR3G60X.jpg)

Masaai ranchers in Kenya now can check market prices for their cattle on mobile phones. Africa’s new undersea fiber-optic cables, which offer high-speed Internet access, are leading an entrepreneurial boom in Kenya and Ghana. Rwanda’s Vision 2020 is centered on a youth-led, knowledge-based economy. The Nigerian government has launched the Single Window Trade Portal to improve trade and standardize services.

With dramatic growth and change come challenges and security threats, from cyber crime and intellectual property theft to espionage and other cyber attacks. To ensure that Africa fully benefits from the e-revolution, governments must take cyber security seriously.

Layers of solutions are emerging. Europe, Asia and the United States, and, indeed, all security professionals can learn from Africa’s approach to cyber security.

Eleven undersea fiber-optic cable systems were completed with international and local investment in the past few years. This has brought faster and cheaper broadband connectivity. Economic growth, urbanization, and a rapidly growing youth population have followed and created new economic opportunities. Cyber cafes have opened in war-torn Somalia; engineers in Kenya, Rwanda and South Africa are building new software for worldwide markets; and from Algeria to Zimbabwe, e-commerce is taking off.

The numbers are impressive. Six of the world’s 10 fastest-growing economies are in Sub-Saharan Africa, which has created the world’s second-largest mobile phone market.

Smartphones outsell computers 4-to-1 in Africa, and an estimated 1 billion mobile phones will be on the continent by 2016. Mobile Internet use in Africa is among the highest in the world. Annual growth in the use of social media such as Facebook and Twitter exceeds 150 percent. There are more than 90 tech hubs, innovation labs and e-incubators in more than 20 African countries.

The political impact also has been profound. The software platform Ushahidi emerged from Kenya’s 2008 postelection violence and lets users crowd-source crisis response. @GhanaDecides educated voters before the 2012 elections, and social media played a role in 2010’s Arab Spring in North Africa.

Challenges to growth

Despite robust growth, Africa’s e-revolution has had several challenges:

- Access to broadband connectivity remains uneven and is focused mostly on English-speaking countries and coastal urban hubs.

- Africa remains a “dumping ground” for secondhand, second-generation mobile devices and personal computers. These devices are more vulnerable to cyber attacks.

- An estimated 80 percent of personal computers in Africa already are infected with viruses and other malicious software.

- Some have used mobile telephony to advocate violence, and states have used their control of Internet access to limit freedom and human rights.

- Yet, on balance, from food security to health care access, and from employment opportunities to democratic freedoms, all facets of life in Africa have benefited from the e-revolution.

Threats to Africa’s e-Revolution

To date, Africa has experienced a honeymoon period with the Internet. Most of the cyber attacks have been limited and unsophisticated. Cyber crime has become local and common, known in Uganda as bafere and in Ghana as sakawa. Criminals typically use off-the-shelf malware, phishing or email-based advance-fee scams, commonly known as Nigerian 419 scams or colloquially as yahoo-yahoo. It is mostly the public that has fallen victim to the attacks. The attacks have had a major economic impact only recently.

Cyber crime has grown with more affordable connectivity and the rise in e-commerce. Accompanying the growth in cellular telecommunications has been the growth in cyber attacks on smartphones. In 2012, South Africa, the most advanced e-commerce market on the continent, also ranked as the world’s second-most-targeted country in phishing attacks.

In October 2013, a variant of the Dexter malware program cost South African banks millions of dollars when it was inserted into point-of-sale devices in fast-food chains. In Nigeria, from 2010 to 2012, there was a 60 percent increase in attacks against government websites, which included attacks against the Central Bank of Nigeria, the Ministry of Science and Technology, and the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission. These are only a few of dozens of instances.

Intellectual property (IP) theft, espionage, the costs of cyber security, and the opportunity and reputational costs associated with malicious online activities are difficult to quantify. As the security software company McAfee and the Center for Strategic and International Studies noted, the economic impact of the theft of IP is probably several times more than the cost of cyber crime.

![A customer uses a tablet computer in a cyber café in the Medina district of Dakar, Senegal. [AFP/GETTY IMAGES]](https://adf-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/170168026.jpg)

As the e-revolution evolves, more IP will emerge from Africa, and the theft of IP and sensitive business information is likely to increase. Similarly, while Africa — except for South Africa — is probably not a significant target of online espionage, the threat is real.

So, too, is the likelihood that some states will develop offensive capabilities, further skewing the military capabilities between rich and poor countries. There is no public information available that an African state or nonstate actor has successfully conducted an offensive cyber attack, but the social media and online presence of such terrorist groups as al-Shabaab in Somalia demonstrates the ease and cost-effectiveness by which nonstate actors can use cyberspace to great effect. And since cyber crime is a transnational issue, African countries and their citizens remain vulnerable to attacks from around the world.

Layers of Solutions

In addition to the threats, Africa faces many cyber challenges. For one, African governments have limited capabilities to enact legislation and enforce it. In Kenya, for instance, less than 50 percent of cyber crimes result in a conviction. Governments have only recently begun to fund cyber security, and they lack information technology (IT) and cyber-security professionals. Laws and regulations covering mobile telephones and Internet service providers are in their infancy, and enforcement can be lax. Corruption is often endemic and spills over into the cyber domain.

The United States and Europe do not offer particularly good examples to follow. They are heavily dependent on the private IT security industry and often behind the curve when it comes to combating cyber crime. Internationally, there is no central repository of cyber knowledge, expertise or training, and African-specific solutions are rarely presented.

Still, several layers of solutions have emerged in Africa, from increasing awareness of cyber crime to establishing computer emergency response teams (CERTs), and from national strategies against cyber security to international collaboration. All will be needed to ensure the e-revolution continues in Africa.

Cyber-crime awareness through education and training is vital in Africa. It includes public and corporate awareness, but most important, lawmakers must be educated on the threats and opportunities related to cyber security.

Only South Africa and Egypt have a significant number of trained cyber-security experts. In recent years, a few countries have passed laws related to cyber security, cyber crime, and data protection, but many already are outdated, and other countries are trying to catch up. Many are requiring mobile SIM card registration, in part, to better control crimes committed on mobile phones. Expertise on cyber-crime issues is needed at all levels and across the government. A positive step can be seen in law enforcement. Countries including Ghana, South Africa and Uganda have created new cyber units within their police forces.

One indication of growing government awareness and capacity is the creation of national CERTs (see sidebar). Eleven African countries have established CERTs, and a continentwide AfricaCERT is based in Ghana. It coordinates incident reporting and promotes cyber-security education and human resource development. Some CERTs have been successful: In 2012, the CERT in Côte d’Ivoire investigated 1,892 incident reports, and authorities made 71 arrests, leading to 51 convictions on cyber security-related crimes.

A national cyber strategy

CERTs are only part of a comprehensive national cyber-security strategy. The strategy can be a vital tool in ensuring that scarce government resources are appropriated to ministries and agencies engaged in cyber security. South Africa is a leader on the continent, developing a national cyber-security strategy in 2010 and inaugurating a National Cyber Security Advisory Council in 2013. Uganda also has a national cyber-security strategy, and Kenya is developing a national master plan.

As the South African and Ugandan strategies demonstrate, it is important for nations to take a whole-of-government approach to ensure that the strategy is effective and will build national capability, not just the power of one ministry. In addition to national strategies, numerous regional and international approaches are improving cyber security in Africa. Regional economic communities have sought to collaborate on cyber security, with the most active being the Southern Africa Development Community and the East African Community.

For the past four years, the African Union has been considering the African Union Convention on Cyber Security, which includes sections on electronic commerce, personal data protection, cyber crime and national cyber security. It has put a special focus on racism, xenophobia and child pornography. But implementation will be a significant challenge, and political will remains an issue. Critics are concerned about the convention’s potential for curbing Internet freedom.

At the same time, leaving cyber security to the private sector in Africa is not a feasible option because corruption, a weak legal framework and the drive for profits do not necessarily align with national security requirements. Academia, think tanks and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) will undoubtedly play important roles, but they lack the financial resources to lead cyber-security efforts.

Africa’s e-revolution cannot, and should not, be stopped. Too many people are benefiting too much from increased global connectivity. Africa’s emerging cyberspace entrepreneurs must be embraced by the global community and by their governments. African research into threats and solutions also are important for any cyber-security strategies to take hold.

Africa’s economic growth will depend significantly on improving cyber security. It is not something that governments should outsource to the private sector or to NGOs. International partnerships and the sharing of best practices are vital, as are assisting in building technical capabilities and legal guidance. Everyone in cyberspace will sink or swim together.

Dr. Eric T. Young is a professor of national security studies at the George C. Marshall Center. His principle interests include African security studies, terrorism and counterterrorism, civil-military relations, and military sociology.

Technology Clusters Emerge Across Africa

ADF STAFF

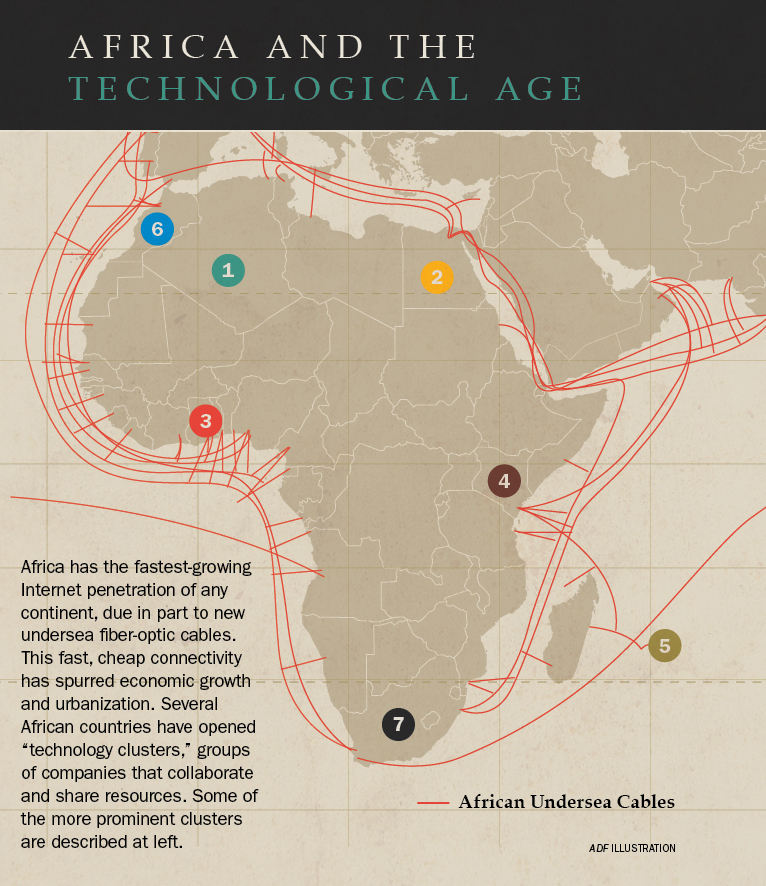

Africa’s technological growth isn’t just in cyberspace. It’s also taking root in some of the continent’s major cities. Developers are seeing the value of grouping businesses in “technology clusters” to maximize efficiency and innovation.

Clusters consist of interconnected companies that share things such as labor market pooling, specialized suppliers and knowledge. Businesses in clusters collaborate and compete, and in some ways depend on each other, according to the South African LED Network. The hope is that the next tech giant like Google or Facebook will emerge from these clusters, sometimes called “cyber cities.”

Recently, technology clusters have developed across the continent. Others are in the planning stages. Below is a list of some of the more prominent clusters operating or under construction:

1. ALGERIA — Cyberparc de Sidi Abdallah: The high-tech center has research space, laboratories and more spread across 100 hectares. It also includes two hotels, retail space and other amenities. When the center was under construction in 2006, Algerian Technology Minister Boudjemaa Haichour told Magharebia.com that the goal is to stimulate technological activity, provide business support for national companies, and accelerate the use of computers in small and medium-size businesses. Activities include electronic component manufacturing and assembly, and software.

2. EGYPT — Smart Village Cairo: Egypt’s first, fully operational information technology (IT) cluster and business park covers 3 million square meters. It includes multinational companies, and governmental, financial and educational organizations. Participating companies include tech giants Microsoft, IBM and InfoBlink, a Cairo-based tech company that produces software to manage fleets, ground transportation and mobile workforce management.

3. GHANA — Hope City: Ghana’s $10 billion technology hub is planned for Accra and will include Africa’s tallest building at 270 meters among its six towers. It will include an IT university, a residential area and a hospital, and social and sporting amenities. “This will enable us to have the biggest assembling plant in the world to assemble various products — over 1 million within a day,” Roland Agambire, head of Ghana technology giant RLG communications, told the BBC. Once finished, the tech park could be home to 25,000 residents and provide 50,000 jobs.

4. KENYA — Konza Technology City: Launched in 2013, the development is 60 kilometers from Nairobi. Its first phase, scheduled for completion in 2017, includes 1.5 million square meters of development on 162 hectares. Once completed, it’s expected to attract 30,000 residents and 16,700 workers. Konza will focus on four sectors: education, life science, the telecom industry, and business process outsourcing and information technology outsourcing.

5. MAURITIUS — Ébène Cyber City: Developed and owned by a subsidiary of Business Parks of Mauritius Ltd., the Ébène Cyber City consists of two “cyber towers” of 44,000 square meters and 16,000 square meters. When construction began in 2001, the development was touted as an information technology hub and an effort to link Asian and African markets, according to 1st2tech.com. Ébène is the home of AfriNIC, the Internet Numbers Registry for Africa, and other IT companies.

6. MOROCCO — Technopark, Casablanca: The Technopark, a public-private partnership, was set up to develop information and communications technology and green tech. Technopark consists of 230 start-ups and small- and medium-size enterprises employing 1,500 people. Technopark opened in Rabat in 2012 and plans to open in Tangier in late 2014. Omar Balafrej, director general of the Moroccan Information Technopark Co., told Magharebia.com that plans also include expansion into Oujda, Marrakech, Agadir and Fes.

7. SOUTH AFRICA — Technopark Stellenbosch: This cluster of 289 companies representing 33 business categories includes the communication, engineering, Internet, software and technology industries. Construction on the park began in 1987.

Readiness Teams Strive to Secure Internet

ADF STAFF

In 2013, Internet security company Symantec determined that more than 552 million identities were exposed via security breaches, Web-based attacks were up 23 percent, and that one in eight legitimate websites had a “critical vulnerability.”

Africa can be especially vulnerable, given that its computer and Internet infrastructure is still developing. In 2013, 73 percent of South African Internet users were affected by cyber crime, according to Symantec. This cost the South African economy about $300 million.

A plan to ensure Internet security is essential. That’s where AfricaCERT comes in.

CERT stands for Computer Emergency Readiness Team. It began in 1988 as a project of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, an independent branch of the United States Department of Defense. Today it focuses on Internet security incidents.

The AfricaCERT Project seeks to unite nations in promoting cyber security. According to its website, it “facilitates incident response capabilities among African countries and provides capacity building, access to best practices, tools and trusted communication at the continent level.”

Countries involved in AfricaCERT are: Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Mauritius, Morocco, South Africa, Sudan and Tunisia. Nations appear to be at varying levels of CERT development. National efforts provide a range of services.

For example:

- The Burkina Faso Computer Incident Response Team is charged with helping government agencies reduce and respond to computer security risks. The team also helps educate the public about cyber threats and cyber crimes.

- Côte d’Ivoire’s Computer Emergency Response Team alerts computer users to software vulnerabilities.

- The Mauritian National Computer Security Incident Response Team monitors public and private security problems and warns system administrators and users about the latest security threats.

- The Sudan Computer Emergency Response Team serves as an early-warning system and collects data on network incidents. It also helps law enforcement agencies gather evidence.

- The Tunisian Computer Emergency Response Team’s website includes computer security alerts with risk analyses. It also has links that citizens can use to report malware and Internet scams.