The Continent Is at the Center of a Three-Pronged Quest for Worldwide Jihad

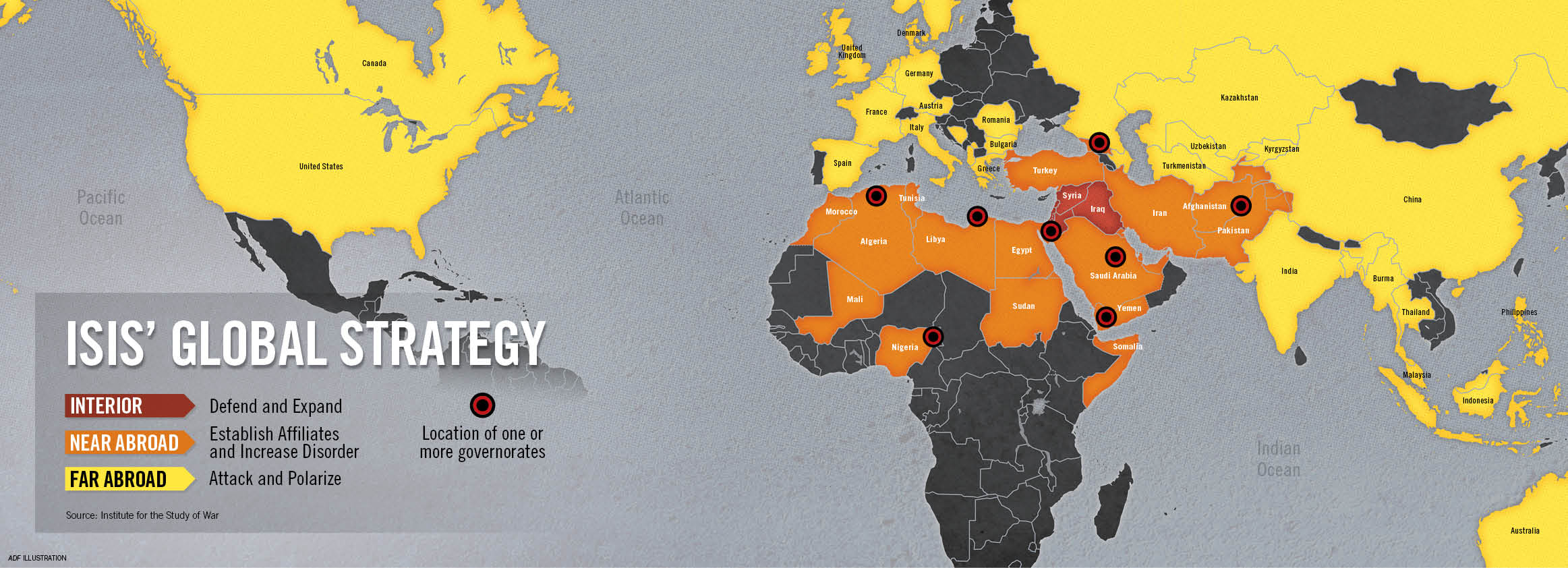

ISIS is advancing its plans for a worldwide caliphate on three simultaneous fronts. Imagine, says Harleen Gambhir, a counterterrorism analyst at the Institute for the Study of War (ISW), a strategy organized in three concentric rings. First, the group is fighting to hold and expand its territory in Iraq and Syria. Next, it is fostering disorder and standing up affiliates in what she calls the “Near Abroad” of the wider Middle East and North Africa. Finally, ISIS militants plan to launch terrorist attacks in the “Far Abroad” of the West, Australia and Southeast Asia.

“ISIS gains influence in areas of disorder and conflict by exacerbating existing fissures in states and communities,” Gambhir wrote in “ISIS’s Global Strategy: A Wargame.” “ISIS’s opponents thus are forced to counter the organization’s ground presence in Iraq and Syria as well as its ability to expand and recruit across the globe. This is a substantial task that involves coherent, yet geographically dispersed efforts, likely coordinated among multiple allies.”

ISIS sees the center of its plan in Iraq and Syria. It was for this reason that the group named itself the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham. Other nations in this inner ring are Jordan, Lebanon and Israel. Moving outward, ISIS is working in the Near Abroad ring, which includes the rest of the Middle East and North Africa, and goes as far east as Afghanistan and Pakistan, according to Gambhir. Expansion in these areas has come as ISIS declares satellite operations by the establishment of “wilayat,” or governed regions. As of September 2015, ISIS claimed wilayats in Algeria, Egypt’s Sinai and Libya.

The process that brought Nigeria-based Boko Haram into ISIS’ orbit was not typical. Typically, Gambhir said, ISIS announces the creation of a wilayat after a group has “coalesced under one leader,” who then reaches out to ISIS with an operating plan for the group’s area. Only then does ISIS approve it and make the affiliation public. Boko Haram, she said, “jumped the gun” on a developing relationship when it pledged its allegiance to ISIS and declared itself the group’s West Africa Province in March 2015. Boko Haram now is known as Wilayat Gharb Ifriqiyya.

Gambhir, who specializes in ISIS’ global strategy and operations, asserts that the Near Abroad, which includes North Africa, is likely to be where ISIS will “strategically surprise” anti-ISIS forces. Such an attack is likely to come in Libya, the country in Africa where ISIS is strongest. Militants already control terrain along the central coast and are imposing sharia and running training camps. In early 2016, ISIS is likely to launch an offensive against Libya’s oil resources, she said.

Gambhir, who specializes in ISIS’ global strategy and operations, asserts that the Near Abroad, which includes North Africa, is likely to be where ISIS will “strategically surprise” anti-ISIS forces. Such an attack is likely to come in Libya, the country in Africa where ISIS is strongest. Militants already control terrain along the central coast and are imposing sharia and running training camps. In early 2016, ISIS is likely to launch an offensive against Libya’s oil resources, she said.

The third element of ISIS’ global plan goes beyond regions where it has an active presence and affiliate organizations. This so-called Far Abroad includes the rest of the world, especially Asia, Europe and the United States. “Of these, ISIS is most focused on Europe, which contains a sizeable Muslim population and is physically more proximate to ISIS’ main effort than Asia or the Americas,” Gambhir wrote.

ISIS wants to defend territory in the Interior and Near Abroad while perpetrating terrorism in the Far Abroad in hopes of “encouraging and resourcing terrorist attacks in the Western world.” By doing so, ISIS hopes that Western governments will alienate Muslims, thus pushing them toward the caliphate, Gambhir wrote. All of these actions are intended to prompt an apocalyptic global war.

AFRICA, A LAND OF OPPORTUNITY FOR ISIS?

Michael Horowitz, senior analyst at the geopolitical risk consultancy Max Security Solutions, told Europe’s edition of Newsweek that ISIS places a significant focus on Africa.

“It has been one of the strategic objectives of IS since the beginning because the problem with IS is that it needs to convey this image of extension,” Horowitz said in April 2015. “Africa is an opportunity because you have a lot of countries that are destabilised, you have existing groups that have drifted away from al-Qaeda.

“They want to keep expanding, they want to hedge their bets,” he said. “What they are saying is that they are making Africa as a place for jihadists. They want to convey to jihadists that Africa is the new Syria, the new Iraq. That’s what they have been doing with Libya for a while.”

Gambhir told ADF that ISIS now is telling recruits that if they cannot reach Iraq and Syria, they should immigrate to Libya and other African countries. The fact that ISIS has affiliates in North Africa operating militarily now widens the possibilities for new recruits, especially those from Africa. “Militant recruitment, I think, is also going to be on an upward trajectory for ISIS in Africa simply because it now has military operations that require fighters that are outside of Iraq and Syria,” she said.

ISIS’ RECRUITMENT IN AFRICA

Some of that potential for new recruits already is being seen. At least a dozen students from the University of Medical Sciences and Technology in Khartoum left Sudan for Turkey on their way to Syria in June 2015. The students — citizens of Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States — are considered prime pickings for ISIS because they are well-educated, do not need money and carry foreign passports, according to an August 2015 article in The National Interest.

“Recruiting ‘foreign fighters,’ as they are called, has been one of the many keys to the success of ISIS,” the article states, “It is also something the group boasts about because its leaders believe it is a major insult to Western governments if their own citizens, who presumably lead fulfilling lives in the West, risk it all to fight with ISIS in Syria and Iraq. The ISIS leadership also uses foreign fighters as evidence that their so-called Caliphate is a viable alternative to Western ideology.”

More than 5,600 people may have left African nations to fight in Iraq or Syria, according to a January 2015 report from the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence. That total represents more than 25 percent of the global sum.

More than 5,600 people may have left African nations to fight in Iraq or Syria, according to a January 2015 report from the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence. That total represents more than 25 percent of the global sum.

Most foreign fighters leaving the continent for Iraq or Syria have come from North Africa.

Smaller numbers of fighters have left other African nations such as Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Eritrea and Mauritania, according to the June 2014 report, “Foreign Fighters in Syria,” published by The Soufan Group. News reports in August 2015 stated that ISIS had recruited up to 10 people from Ghana.

ISIS, seeing evidence that some al-Shabaab factions have begun to favor the group, began an effort to recruit Somalis. The outreach includes videos aimed at the Somali “mujahideen” — Arabic for “holy warriors” — and a media outlet set to produce Somali-language content.

WHAT CAN AFRICAN NATIONS DO?

Countering ISIS in Africa will not be easy. Libya complicates matters by not having a unified military or government. ISIS has been able to take advantage of the chaos to establish safe havens. Other countries, including Nigeria and Somalia, have their hands full battling domestic insurgencies such as Boko Haram and al-Shabaab, respectively.

REUTERS

Morocco has had some success in the past year, regularly raiding terrorist cells with links to ISIS. In June 2015, the nation’s Central Bureau of Judicial Investigations, established the same year as part of the kingdom’s beefed-up war against extremism, broke up a seven-member terrorist cell aligned with ISIS. The government said the group intended to kidnap and murder tourists at seaside resorts, the Daily Mail reported.

Nations such as Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia will need to continue to degrade terrorist networks while trying to prevent a major attack, Gambhir said. If a significant terrorist attack does get through, as happened in Tunisia when a gunman killed 38 and wounded nearly 40 others at a resort near Sousse, authorities will need to manage the national reaction to prevent ISIS from using the attack to destabilize the country.

ISIS is an organization with an apocalyptic narrative. It is trying to incite disorder, and eventually war, with those not a part of its self-proclaimed caliphate. Although military action may seem to play into extremists’ hands, inaction also gives ISIS a reason to claim victory, Gambhir said.

“Rather, I think what we need to do from that narrative perspective is compete, to create a narrative that actually challenges ISIS in terms of what it says that it’s doing,” she said. “It says it’s established a state; we should have a narrative campaign that’s focused on proving that ISIS has not done that. … We should be constructing a narrative that can compete with ISIS’ narrative.”