The continent’s growth is ‘nearly unprecedented in human history.’ It will require planning and skilled leaders.

ADF STAFF

Habib Bourguiba was decades ahead of his time. In 1957, he became the first president of Tunisia. Over the course of his administration, he changed the social fabric of the country, particularly in the area of women’s rights.

In a mostly Muslim country, Bourguiba gave women full citizenship, which included the right to remove their veils and the right to vote. He created a national health care system. He banned polygamy, gave women the right to divorce, and made sure that girls and boys got a primary school education.

Incredibly for that time, he legalized birth control and abortions for women with large families. Robert Engelman of the Worldwatch Institute, writing for Scientific American magazine in February 2016, said that by the mid-1960s, mobile family-planning clinics throughout Tunisia were offering birth control pills.

Bourguiba was removed from power in 1987, but he left behind a unique plan for his country to deal with one of the biggest changes in the world in the 21st century: Africa’s population boom. Today, Tunisia has what demographers call a balanced age structure. That means the population is relatively evenly distributed among the young, middle-aged and old.

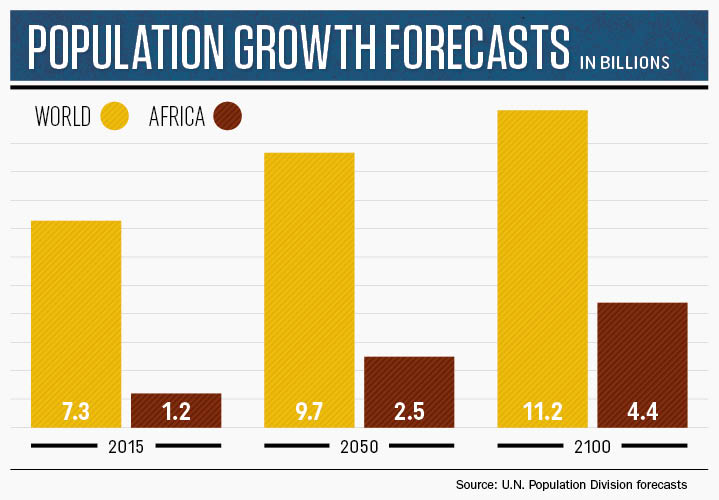

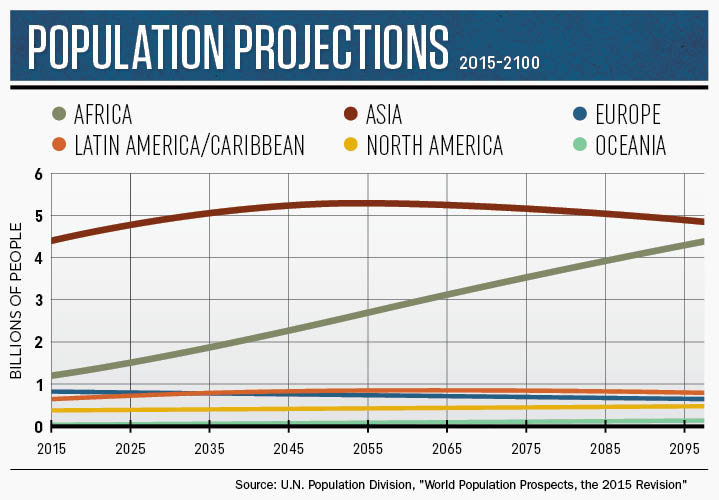

Tunisia, however, is an anomaly on the African continent, which has the youngest population on the planet. Numerous projections, including those by the United Nations, say that Africa’s population, currently at 1 billion, will double by midcentury and reach 4 billion by 2100. Other studies project even faster growth. Social scientists say that Africa’s growth will have a tremendous effect on the rest of the world. The Washington Post has described the growth as “nearly unprecedented in human history.”

The figures speak for themselves: According to the United Nations, Africans make up 16 percent of the world’s population. By 2100, if current rates continue, Africans will make up 39 percent of the world’s people.

A key statistic is the total fertility rate — the number of children a woman is likely to have in her lifetime. The total fertility rate for Africa is 4.7 children per woman, compared with 2.5 children globally. In Niger, one of Africa’s poorest countries, the average woman will bear more than seven children during her life. By midcentury, Niger’s population is projected to nearly quadruple.

This growth is not a new thing. The continent’s population has nearly tripled since 1980. By midcentury, the continent is projected to add 80 people per minute. Nigeria, the world’s seventh-most-populous country, is expected to add more people to the world by 2050 than any other country.

These statistics are a dramatic change from earlier projections. As recently as 2004, the U.N. expected Africa to grow only to 2.2 billion people by 2100. Demographers had looked at the falling birthrates in Asia and Latin America and projected that the same changes would take place in Africa. That has not been the case.

Even before Africa’s population began to mushroom, the continent’s leaders had taken notice. Kenya began working on population control policies in 1967; Ghana followed two years later. By 2003, 77 percent of Africa’s Sub-Saharan nations had announced policy initiatives to slow down their countries’ growth.

VIRTUOUS CIRCLE

Other parts of the world have used national family planning programs to trigger a virtuous circle. Contraception has led to declines in fertility rates. The declining rates have allowed for more resources, such as education opportunities, to be used per capita. With more education, women and girls have helped economies grow and improved their social status.

A failure to address population growth leads to crowded schools, congested roads and rocketing housing costs.

There are many reasons why Africa’s projected growth rate is so big. Perhaps foremost is its overall health. The United Nations said life expectancy in Africa rose by six years, to 59, in the 2000s. By the year 2100, Africa’s average life expectancy could hit age 78.

In the past decade, the U.N. said, the rate of African children dying under the age of 5 went from 142 per 1,000 to 99 per 1,000. It is still twice the global rate, however.

In the past decade, the U.N. said, the rate of African children dying under the age of 5 went from 142 per 1,000 to 99 per 1,000. It is still twice the global rate, however.

The main reasons for Africa’s population boom remain societal. In many parts of the continent, large numbers of children are needed in families to work the land, which is often poorly suited for farming. The men in many African countries regard large numbers of children as a status symbol, as well as proof of their virility. Access to contraceptives is limited in many areas.

There also is the matter of Africans not wanting to be told what to do by the rest of the world. In an October 30, 2015, interview with the Catholic News Agency, Ugandan priest Herman-Joseph Kalungi said the push for contraception is “a question of some Western forces imposing some customs, imposing some ways of living that are contrary to our culture.”

“Instead of helping us to grow more food, instead of helping us to establish maybe factories or to be able to get medicines, they will suggest you have less children so you don’t have the problem of hunger,” Kalungi said.

The biggest single reason for the population boom is that many African women do not control their own destinies. They are at the mercy of their husbands, their own lack of education and opportunities, or poor leadership within their countries.

SECURITY CONCERNS

In a 2011 report titled “The demographic nightmare: Population boom and security challenges in Africa,” Nigerian political scientist Azeez Olaniyan warned of the security consequences of Africa’s rapid population growth without a corresponding increase in infrastructure and job opportunities.

“These include a youth bulge, rural-urban migration, land pressures, environmental issues and a depletion of natural resources,” he wrote. He added that “when a mass of youths are jobless or underemployed, their propensity for taking up arms in exchange for small amounts of money, as well as the likelihood of their being drawn into criminal gangs, is very high.”

“In other words, unemployment, a product of unrestrained population growth, fuels conflict and crime.” This becomes particularly acute, he said, in any country with many years of military rule.

Engelman said many African leaders fear the security implications of a future that is “crowded, confrontational and urban.”

A United Nations study warns of the dangers of Africa’s labor force outgrowing the number of jobs available, creating “a menacing problem for society.”

“Rapid population growth rates also have ramifications for political and social conflicts among different ethnic, religious, linguistic and social groups,” the U.N. study said. Population growth will be a “major contributing factor” in violence and aggression among young people and could “form a disruptive and potentially explosive political force.”

AFRICA’S CITIES

It is impossible to discuss Africa’s population boom without considering its cities, particularly its megacities. The Democratic Republic of the Congo’s capital, Kinshasa, is expected to grow to 20 million people by 2030, while Lagos, Nigeria, will hit 24 million; that’s the current population of Shanghai, China, one of the largest

cities in the world.

In the 50 years from 1960 to 2010, the population of Africa’s big cities increased from 53 million to 401 million. Africa now has 50 cities with more than a million people. By 2025, there will be 23 more.

Dr. Richard Cincotta, a demographer who has studied Africa extensively, told ADF that a lack of job opportunities in rural areas will continue to drive the growth of cities. “There’s nothing for young people to do in the country, so they migrate to the city,” he said.

Africa’s future echoes that of China. Like China, Africa is rapidly urbanizing. Many, if not most, of the new arrivals to Africa’s cities come from failed farms. These newcomers, mostly young people, Engelman said, settle into slums, “scratching out what shelter and livelihoods they can.”

David Anthony of UNICEF said African leaders can make all the difference by planning for urban growth.

David Anthony of UNICEF said African leaders can make all the difference by planning for urban growth.

“We want to see African leaders make the correct and right investments in children that are needed to build a skilled, dynamic African labor force that’s productive and can grow, and can add value to the economy,” he told National Public Radio. “The worst thing would be if this transition was just allowed to happen, because what you’re going to see is an unparalleled growth of the slum population.”

THE NEED FOR ELECTRICITY

Olaniyan’s report emphasizes the need for infrastructural renewal to keep up with Africa’s population growth. Specifically, he said, Africa needs more electricity.

“Few African states generate an adequate supply of electricity,” Olaniyan wrote. “The improvement of electricity supply throughout the continent would remove the majority of inhabitants from the vicious circle of poverty, thus eliminating a major cause of conflict.”

One specific benefit of improved electricity access throughout the continent would be that fewer young people would feel compelled to move to the cities. A lack of electricity also has stifled commerce in vast expanses of the continent. Even in developed areas and cities, merchants and manufacturers complain that they have to shut down their businesses regularly because of a lack of reliable power sources.

Economists have warned that the countries in Africa without adequate power will have stagnant economies, which in turn will discourage new investment. Power in the coming years will be the key driver of growth.

Improving Africa’s access to electricity is not an overwhelming task. Many parts of the continent have the potential for vast hydroelectric resources. Some authorities believe that the Congo basin alone has the capacity to supply most, if not all, of Africa’s electrical needs.

PROMOTING POPULATION CONTROL

Controlling the booming population numbers remains the primary means of improving the quality of life on the continent. Other parts of the world, most notably India and China, have addressed the problem in their own ways.

In 1978, China initiated a “one child” policy, officially restricting the number of children married couples could have. Chinese officials enforced the policy with fines and taxes. Chinese farmers, who need sons to work their farms, were particularly affected. The policy led to allegations of families killing infant daughters, forced abortions and mandatory sterilizations. The policy ended in 2016.

India recognized the need for family planning as early as 1949 and started a nationwide birth control program in 1952. It later included family health and nutrition. India updated its birth control programs in 1966, 1977 and 1994. Some aspects of India’s programs, including a 1970s forced sterilization stipulation for men with two children, failed.

Although Indian women are aware of the need for contraceptives, such supplies are often unavailable. The current birth control plan, introduced in 1994, calls for universal access to contraceptives, a minimum marriage age of 18, training for people who assist with births, and a broader education for more of India’s youth. The India plan is considered a model for other parts of the world to follow, including Africa.

China has proved that heavy-handed enforcement of birth control is not the answer. Culturally, Africa’s 54 countries require, as Olaniyan put it, “sustained persuasion, enlightenment and education” to make birth control goals attainable.

Cincotta told ADF that one of the keys to sustainable growth on the continent is strong leadership, particularly leaders who “feel strongly about women participating in society.”

When government leaders insist on women’s rights, Cincotta said, it triggers a chain reaction. Women receive a good basic education, they move into the workplace, fertility rates go down, and government services improve because there are fewer people to serve. Incomes go up, education continues to improve and the crime rate goes down.

In their 2013 study “African Demography,” researchers Jean-Pierre Guengant and John May said that any country aspiring to prosperity must first reduce its birthrate. Doing so, they said, produces a “demographic dividend.”

Improve infrastructure, create jobs

The BBC asked Obadiah Mailafia, a former deputy governor of the Central Bank of Nigeria, how Africa needs to plan for its population boom.

If you go to many of our cities these days, they’re much more crowded than ever. So huge challenges are deriving from the population increase, and it is quite palpable. You could see it not only in heavy traffic, but also pressure on social services, the water, electricity, schools and the rest of it.

In some of our biggest airports, there is now pressure on space for parking of private jets. And yet the streets are booming with poor people, people hustling in the streets because they have no opportunities and no hope for the future.

My worry is the fact that we are not making arrangements to cater for this rising population. There’s no country in the world that I know of that has over 70 million people that does not also have a flourishing rail network. The roads are cluttered up with heavy trucks. And also expanding social services like health, education and the rest of it — all those things need to be in place, together with better planning for population and for families.

We must create jobs, we must expound opportunities for young people to get them engaged and busy, otherwise we might find that the sort of thing that happened in the Arab Spring could happen in Nigeria.

Political will needed

John Wilmoth, director of the Population Division of the United Nations, gave his thoughts on Africa’s growth to the BBC in September 2015.

There’s been a substantial reduction in the death rate in Africa, like in other parts of the world, and this is good news in many ways — children survive in much greater numbers to adulthood, and adults survive to old age.

However, what’s preventing that kind of movement in a similar direction to what’s happening in the rest of the world is our continued levels of high fertility. You always have three things together: You have high fertility, rapid growth and young populations.

Currently in Africa we estimate that 41 percent of the population is under the age of 15. This is a very high fraction. Another 19 percent are between ages 15 and 24. So if you add those two together, you’ve got three-fifths of the population that is under the age of 25.

We really need political will at the highest levels paying attention to this issue because it really will affect the ability of those countries to raise the standard of living for their populations, and it will have long-term implications for the well-being of that part and the rest of the world as well.

Extreme Poverty is the Problem

Hans Rosling, professor of international health at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden, told the BBC that population growth by itself is not the issue.

What is difficult for the surrounding world is to realize that Africa will become a much more important part of the world. And I see that because so many big investment banks invite me to come and lecture because they see, “Wow! There’s economic growth in Africa. Wow! Companies in Africa are profitable today.” They see customers.

The reason the population is growing in Africa is the same reason that [saw] population growth first in Europe, then in the Americas, then in Asia. It’s when the population goes from a phase where you have many children born and many who are dying. Then the death rate goes down, and [some time later] the birthrate follows.

Addis Ababa has 1.6 children per woman, which is less than London. So when you hear an average of Africa of 4.5 children per woman, that is composed by the most modern part of Africa with two children per woman [or less] and the still worst-off, in very extreme poverty, with six to seven.

I can see government after government in Africa getting it. Presently we see Ethiopia, Rwanda, Ghana doing the right things, and others are coming fast.

If you continue to have extreme poverty areas where women are giving birth to six children and the population doubles in one generation, then you will have problems. But it’s not the population growth that is the problem — it’s the extreme poverty that is the underlying reason.