Cameroon evolves to thwart Boko Haram’s changing tactics

ADF STAFF

Photos by The Cameroonian Armed Forces

On the afternoon of October 15, 2014, Boko Haram launched an audacious attack. About 1,000 fighters crossed the barren border that separates Cameroon and Nigeria and surrounded the town of Amchidé. Young foot soldiers armed with AK-47s and known as crieurs for their fanatical shrieks made up the first wave. Next, older fighters rushed in on pickup trucks mounted with machine guns. Last came three tanks crushing everything in their path. The insurgents overran a police station and a gendarmerie post and took control of the city, executing civilians who could not prove they were Muslim.

The marauders continued on to an encampment of Cameroon’s Rapid Intervention Battalion (BIR) 1.5 kilometers away, where they detonated a car bomb.

Understanding that they were greatly outnumbered, the BIR contingent defended its camp and called for reinforcements. Within three hours, about 1,000 BIR Soldiers from other camps in the region had responded and launched a counterattack that lasted nearly two days. By the end of the siege, the Cameroonian military had taken back two occupied cities and killed 107 Boko Haram fighters while losing eight Soldiers.

Cameroon’s military chief of operations in the zone, Maj. Leopold Nlate Ebale, said it was an attack on an “unprecedented scale” on Cameroonian soil.

The assault alarmed observers not just for its boldness, but also for its sophistication. Earlier in the day Boko Haram had sent an envoy to the camp with false information, hoping to divert some of the military’s manpower. The terror group also conducted a second attack simultaneously in the nearby town of Limani and tried to destroy a bridge to isolate the area.

The assault alarmed observers not just for its boldness, but also for its sophistication. Earlier in the day Boko Haram had sent an envoy to the camp with false information, hoping to divert some of the military’s manpower. The terror group also conducted a second attack simultaneously in the nearby town of Limani and tried to destroy a bridge to isolate the area.

“They had become an extremely fearsome force,” Col. Didier Badjeck, head of the Cameroonian Defense Ministry’s communications division, told ADF. “The first attacks that we sustained between the month of May and the month of October [2014] were frontal attacks, well-organized, by a terrorist force that was heavily armed with tanks.

We understood that we were facing more than simple terrorists; they had the methods of operations of a military.”

There was good reason for this. For a year, Boko Haram had looted weapons depots and consolidated power in northeastern Nigeria. By the time it crossed into Cameroon, it had amassed a miniature empire including 14 local government areas and 30,000 square kilometers, an area roughly the size of Belgium. The attacks made it clear that Boko Haram members were not satisfied with the territory they held. They wanted to expand.

Northern Cameroon was a natural next step. The region is cut off geographically, economically and culturally from the rest of the country. It is underdeveloped with a 70 percent poverty rate, and many young men there need employment. “No matter the indicator — access to health care, access to education, access to clean water — it’s ranked last in all of them,” said Guibai Gataba, publisher of the newspaper L’oeil du Sahel and a native of northern Cameroon. “The population is huge, and there’s just no work.”

Many people in the north share ethnic and linguistic ties with people in northern Nigeria. The region has long been a carrefour, or crossroads of cultures, with people moving easily back and forth between Cameroon, Chad and Nigeria selling illegal and legal merchandise.

“The border, in reality, it didn’t exist physically,” Badjeck said. “It could be desert, it could be swamp when it rains, but you go from one side to the other without recognizing it.”

Boko Haram’s leader, Abubaker Shekau, announced in a 2014 video message that he had created a caliphate, and its capital was the town of Gwoza, Nigeria, less than 10 kilometers from the Cameroonian border. At the time his forces outnumbered Cameroonian forces in the north 3 to 1.

A strategic shift

By mid-2014 the response to the threat was beginning to take shape. Cameroon’s President Paul Biya declared war on Boko Haram in May at an event with other presidents from the Lake Chad Basin region who had gathered for a summit at the Élysée Palace in Paris.

After the declaration, Cameroon’s military restructured its forces and divided the former 3rd Inter-Army Military Region that had included much of the north into two new regions with bases at the front lines of the fight. The newly created 4th Inter-Army Military Region headquartered in Maroua became the nerve center of the effort. “This decreased the response time and allowed us to have a command post right beside the action,” Badjeck said. “This was a decision that was extremely important at a politico-strategic level.”

Cameroon also began promoting younger officers with experience in the north and knowledge of Boko Haram tactics to command units on the front lines. It repositioned the Motorized Infantry Brigade to Kousseri in the north, across the river from N’Djamena, Chad, and beefed up the presence of the gendarmerie, creating new outposts to clamp down on traffickers and cross-border activity.

“We switched from a phase of containment of the threat to a phase of taking initiative,” Badjeck said.

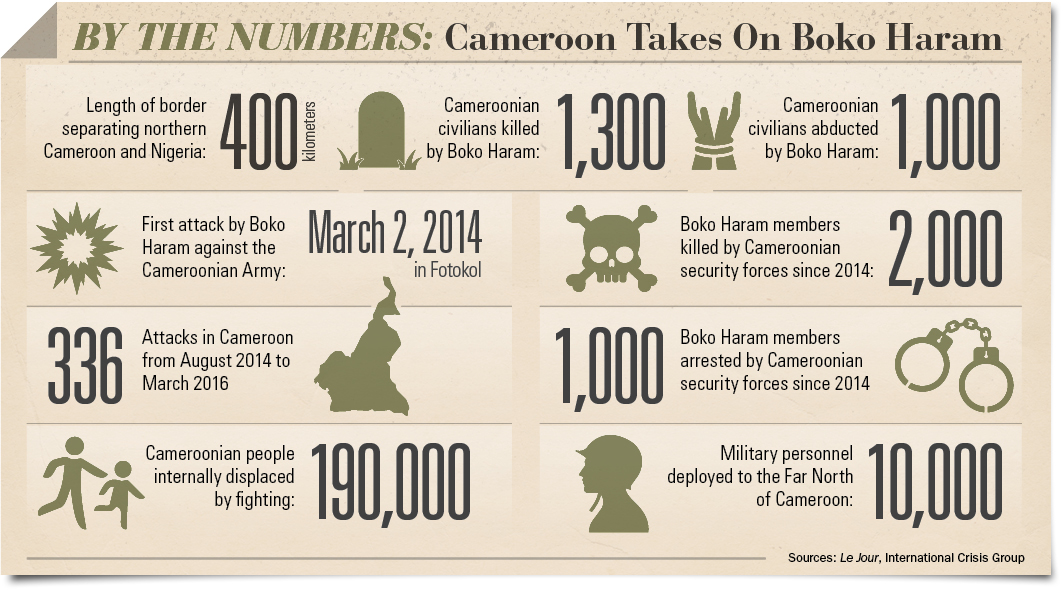

The military launched two missions. One, Operation Alpha, was staffed by the nation’s elite BIR, which doubled the number of troops stationed in the region in July 2014 to 2,000. The second, Operation Emergence, was commanded by the Army. Gradually, the total military presence in the north grew to nearly 10,000 Soldiers.

Something else important happened. The military branches, sometimes criticized for being mistrustful and cut off from one another, began working together. This phenomenon, termed “interarmisation,” occurred at the urging of the president and minister of defense, but also was due to the unique demands of the fight. Many missions required the speed of the BIR and the heavy firepower of the Armored Reconnaissance Battalion and the Ground-to-Ground Artillery Regiment. Some missions also called for the close air support of the Air Force’s Mi-17 or Z-9 attack helicopters. Some missions to clear the islands of Lake Chad required the expertise of the Marines.

“You began to see a change in the way different units interacted,” said Hans De Marie Heungoup, a Cameroonian security expert and analyst with the International Crisis Group. “The gendarmerie, the Soldiers from Emergence 4, the BIR from Operation Alpha were cooperating.”

The posture paid dividends. In December 2014, Boko Haram fighters invaded and occupied the tiny town of Achigachia on the Cameroon side of the border. Ground forces conducted a tactical retreat from the area and called for air support. Under direct authorization from the president, Alpha Jet pilots flew bombing raids that neutralized the Boko Haram threat. The overwhelming response ended Boko Haram’s efforts to control land inside Cameroon.

The posture paid dividends. In December 2014, Boko Haram fighters invaded and occupied the tiny town of Achigachia on the Cameroon side of the border. Ground forces conducted a tactical retreat from the area and called for air support. Under direct authorization from the president, Alpha Jet pilots flew bombing raids that neutralized the Boko Haram threat. The overwhelming response ended Boko Haram’s efforts to control land inside Cameroon.

“This was the second stage of this conflict,” Badjeck said. “With this there was a lot of shock, a lot of contact, and never again were the terrorists of Boko Haram able to successfully occupy Cameroonian territory.”

Asymmetric phase

As Boko Haram found itself unable to hold territory, it resorted to asymmetric tactics. Badjeck said the extremist group commonly hid mines and improvised explosive devices (IEDs) along roads.

Boko Haram became three times more likely to use bombs in 2014 than in 2013, according to research published in the journal Scientific Bulletin. Victims were twice as likely to be civilians during this time, and the use of children and women in attacks increased.

Badjeck said this was evidence of the sophistication and the depravity of the foe. “You have to understand that Boko Haram isn’t stupid,” Badjeck said. “They reflected on it and realized that the strongpoint of the Cameroonian Army is its flexibility and mobility, so to hit the center of gravity of the Army they had to create a problem for their mobility.”

In response, Badjeck said, Cameroonian units relied heavily on demining training they received from France and the United States. They began intensive surveillance of the roads aided by drones and spearheaded by a newly created gendarmerie unit assigned to the north. The gendarmes from the squadron known as ERIGN4 increased the number of checkpoints on roads, and used mirrors, metal detectors and hand-held scanners to look for bombs.

“It took three to four months for the military to adapt [to the asymmetric conflict],” Heungoup said. “Also, it took a kind of shift for them to adjust their planning. Now due to the threat of IEDs, they said, ‘Maybe we should not go everywhere as we used to on the road.’ It needs to be done more carefully.”

In February 2015, Boko Haram responded again by changing its targets from roads to civilian locations such as markets and increasing the use of suicide bombers. In three months during the summer of 2015, suicide bombings killed 100 people and injured 250 in northern Cameroon. Of the 34 suicide bombings recorded in Cameroon through March 2016, 80 percent were committed by women or girls.

A regional effort

Although Cameroon made progress in foiling asymmetric attacks, commanders realized they were simply reacting to the problem and not addressing its source. They needed to dismantle the training camps and safe havens inside Nigeria. Beginning in June 2015, Cameroon was allowed to exercise an unwritten “right of pursuit” to cross the border and attack Boko Haram targets on Nigerian soil. Concurrently, the region activated the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) under the umbrella of the Lake Chad Basin Commission and the African Union. Headquartered in N’Djamena, the MNJTF is authorized for 8,700 troops and includes four operational sectors in Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria.

Cooperation and intelligence exchanges have improved since these developments. “More and more intelligence is gathered through the MNJTF and even bilaterally,” Heungoup said. “Often the Nigerian Army will call the Cameroonian Army to alert them of the situation, and vice versa. There has been quite a bit of progress in terms of sharing the intelligence and even sharing the operational plan, which is not something we always see in the coalition.”

Evidence of this partnership was on display during two missions in February 2016 in Kumshe, Nigeria, and Ngoshe, Nigeria. Here, Cameroonian and Nigerian military forces worked hand in hand to attack and dismantle artisanal weapons factories where many of the IEDs are produced and young people were indoctrinated and trained to become suicide bombers. In Kumshe, Cameroonian forces were supported by their Nigerian counterparts who blocked roads and prevented a strategic retreat on the part of Boko Haram. In Ngoshe they uncovered four artisanal bomb factories with large stores of batteries, triggers and suicide vests ready to be used.

“We realized that there needed to be greater cooperation with Nigeria, and Nigeria accepted that under the banner of the MNJTF,” Badjeck said. “This produced a lot of results, and we have noticed that since we started hitting these bases, there aren’t any suicide attacks. That means that the action that we have put forth is a strong action.”

Despite the progress, the fight is far from over. In the 12 months ending in August 2016, Boko Haram launched 200 attacks in the extreme north of Cameroon, the magazine Jeune Afrique reported. Many of these attacks were low-level raids with Boko Haram members stealing cattle or searching for provisions during the night. Other attacks targeted the civilian comités de vigilances — vigilante groups that offer security to villages. About 190,000 Cameroonian civilians have been internally displaced by the violence and are afraid to return home.

Cameroon military leaders are confident they will defeat the threat, but they caution that this will require patience and vigilance for whatever the next phase brings.

“The enemy regularly adapts,” said Lt. Gen. Rene Claude Meka, head of Cameroon’s Army Command Staff. “In terms of perspective, we believe that we are in a fight that could stretch out over a long period of time. Because even as the military capacities of the enemy appear to weaken, its capacity to inflict damage will last for a long time.”

The Multinational Joint Task Force at a Glance

The Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) was established in 1998 to deal with highway robbers and transnational crime in the countries surrounding Lake Chad. The idea was to join forces and prevent criminals from finding safe havens or crossing borders to evade justice.

Formed by the nations of the Lake Chad Basin Commission (LCBC), it was rarely used until 2012 when the countries relaunched it to deal with Boko Haram. Funding and agreeing on an operational plan and force structure proved difficult and caused delays. In October 2014, member states Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria pledged troops to the MNJTF, which is authorized for 8,700 Soldiers. Benin, which is not in the LCBC, also has pledged to contribute troops. The force’s headquarters is in N’Djamena, Chad, and it is commanded by a Nigerian general with a Cameroonian serving as deputy and a Chadian serving as chief of staff.

The force became partially operational in November 2015, although not all countries had fulfilled their troop contribution pledge at that time. Hans De Marie Heungoup, a Cameroonian security expert and analyst with the International Crisis Group, said the MNJTF is making strides but is serving mostly as a coordinating mechanism as opposed to being a truly integrated force. When a mission is planned, all member nations have input through the mechanism and can offer troops as needed and grant authorization to operate on their sovereign territory if requested.

“You cannot say yet that the force is integrated like a NATO force,” Heungoup said. “It’s just to coordinate now; it is not yet a unified force. Each of the forces is based in their own territories.”