Sex and Gender-Based Violence Can Hamper Missions and Tarnish Militaries

ADF STAFF

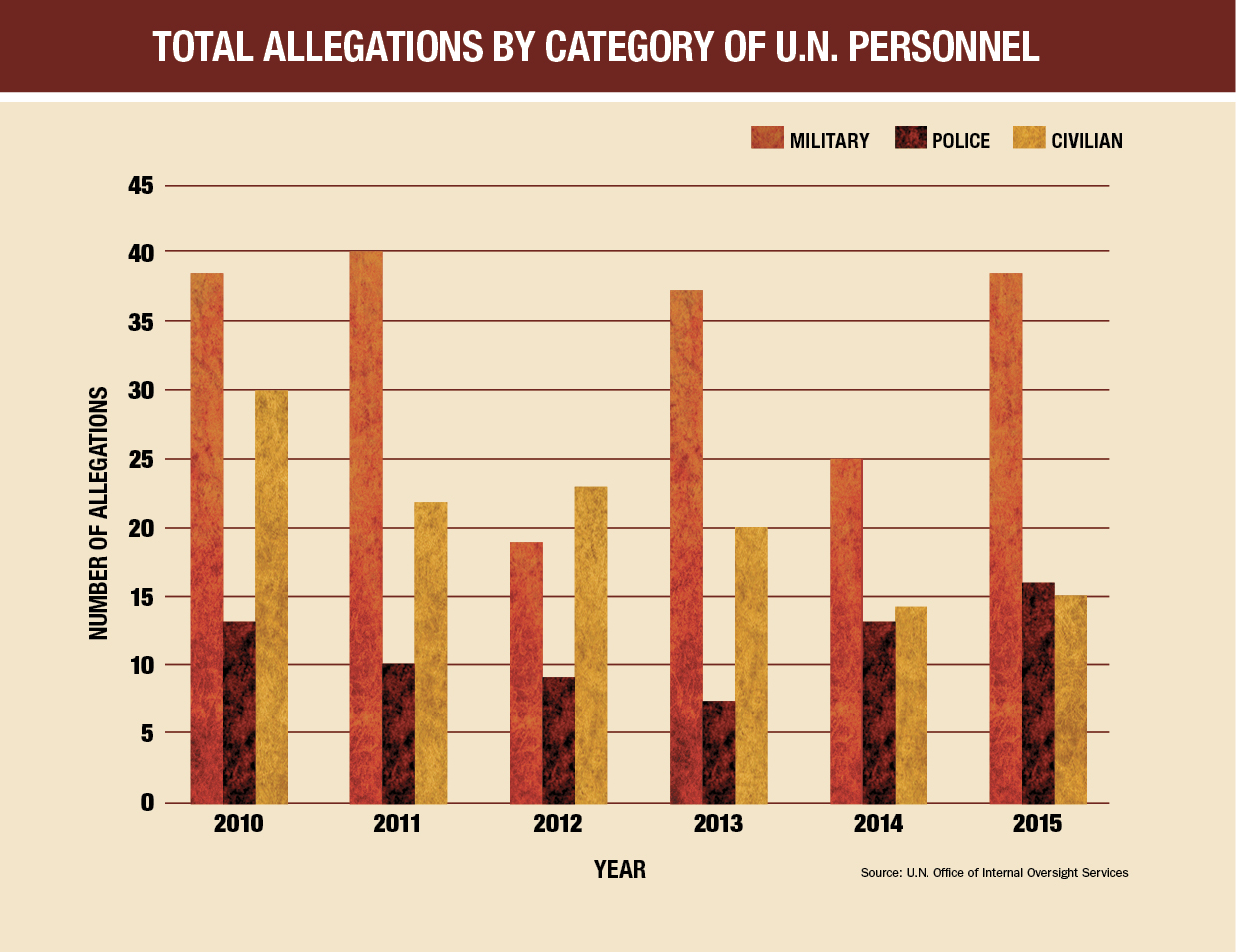

Sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) and sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) have been major problems in peacekeeping missions for many years. Missions in Bosnia, the Central African Republic (CAR), the Democratic Republic of the Congo and others have reported sexual assaults in the past 20 years. These accusations harm the credibility and effectiveness of these missions.

Current unrest in the CAR has provided one of the most egregious examples of peacekeepers abusing civilians. According to the International Business Times, an internal United Nations report indicates that peacekeepers abused 10 to 12 boys ages 8 to 15, exchanging food and money for sex at a camp for internally displaced people in Bangui between December 2013 and June 2014.

The size, scope and complexity of international peacekeeping missions can complicate efforts to prevent SGBV.

For example, as of March 31, 2016, the Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA) had 9,799 Soldiers, 1,896 police officers and more than 1,000 other personnel. Forty-eight nations contributed people to the mission. The number of troop-contributing countries (TCCs), the disparate number of personnel with varying levels of training, the prevalence of vulnerable civilians, and the absence of peace and government institutions in the host country combine to make addressing SGBV all the more complicated.

Ugandan Maj. Gen. Fred Mugisha recalls the conditions he faced during his tenure as force commander of the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) from 2011 to 2012.

Ugandan Maj. Gen. Fred Mugisha recalls the conditions he faced during his tenure as force commander of the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) from 2011 to 2012.

When the peacekeeping mission began in 2007, Somali government forces were composed of undisciplined militants who had served various warlords across the country. Mugisha’s AMISOM forces came from several nations, each bringing Soldiers with varying levels of training and knowledge. Those troops had to work with Somali forces.

“The AMISOM troops were better trained, better equipped, but I don’t think different countries had a unified standard in as far as protection of gender-based violence was concerned,” Mugisha told ADF.

SGBV includes a range of offenses such as rape, assault, forced/early marriage and even human trafficking. The U.N. says sexual exploitation is “any actual or attempted abuse of a position of vulnerability, differential power, or trust, for sexual purposes, including, but not limited to, profiting monetarily, socially or politically from the sexual exploitation of another.” In peacekeeping missions, SGBV/SEA has often involved the rape and sexual abuse of women, men, boys and girls. Sometimes, food or other resources are traded for sexual favors. This is an abuse of the peacekeeper’s responsibility to safeguard civilians.

Once an incident is reported, new challenges emerge: The crimes are committed in a nation with no functioning government structure or institutions. The responsibility to prosecute rests with the TCC that sent the accused soldier, who must be sent to his home country for prosecution. Repatriation creates immediate problems with evidence and access to victims. Even if the TCC prosecutes, it will happen away from the victim and the community in which the crime occurred.

“But the offended — the person whose rights have been violated — will not be in the TCC to see to it that law and justice has taken course,” Mugisha said. “What does that do? It causes mistrust. They think you have simply repatriated the suspect and justice will not take place. And that, of course, creates certain negative feelings.”

ADDRESSING THE PROBLEM

Making headway against sexual violence and exploitation will require training at multiple levels and a commitment to seek justice when crimes are committed. Neither will be easy, but there are hopeful signs that the issue is getting more attention in Africa. High-profile cases have brought the problem to the public’s eye, and continued attention will chip away at the perception of impunity so often associated with the violations.

Thembile Segoete, principal legal officer at the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights, spent 10 years prosecuting various crimes, including rape, in her native Lesotho. She also prosecuted two sexual violence cases between 2006 and 2009 as part of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. She dealt with five more cases on appeal between 2010 and 2014 and has addressed SGBV at the policy level.

“As a prosecutor, my belief is that these crimes should be punished in the way that other crimes get punished, which is by imprisonment, mostly,” Segoete told ADF, adding that offenders also should be dismissed from the military. Too often, the acts can be viewed in the context merely of bad behavior, which minimizes the severity and seriousness of the offense.

Effective prosecution of SGBV in peacekeeping missions, Segoete said, would have various entities involved at different levels:

Troop-contributing countries: The United Nations holds TCCs responsible for investigating and ultimately prosecuting or disciplining their own soldiers when they are accused of SGBV offenses. This typically is done after accused troops are repatriated to their home countries.

Repatriation complicates matters in that it removes the accused from the accusers, and it can make it easier for nations to ignore accountability. One way around this, Segoete said, is to give host nations “subsidiary duties to prosecute.” That way, if a country fails to live up to its responsibilities, then the host nation could take action.

Cynthia Petrigh, founder and director of Beyond peace, a Singapore-based peace support and human rights consultancy, said when TCCs prosecute, they could bring judges and lawyers to the host nation and try cases there “so that everyone knows there is justice.” Doing so also would simplify the presentation of evidence and witnesses.

The host country of the peacekeeping mission: Host nations should investigate and report to the mission sponsor — the U.N., European Union or African Union — and the TCC. Doing so brings attention to the problem and holds the TCC accountable.

Peacekeeping mission commanders: A mission commander’s first duty when learning of SGBV offenses “is to take all measures necessary to stop it,” Segoete said. The commander also should report to the TCC and mission sponsors.

Mission sponsors: Groups such as the U.N. should investigate based on reports received from other stakeholders, consider recommendations of the mission commander, and hold the TCC accountable for prosecuting offenders.

THE VALUE OF SENSITIZATION AND TRAINING

Most of the work to combat sexual violence should be done before crimes occur. This requires proper training for military personnel and informing civilian populations of their rights before a mission begins. Conditions in host nations make civilians especially vulnerable to abuse and exploitation.

“There is no peace; people are always running for their lives,” Segoete said, adding that host countries typically lack stability and the institutions through which victims can report that they have been sexually violated. This lack of security and sense of desperation makes civilians vulnerable and easily coerced into relationships based on their need for protection or humanitarian aid, such as food or medicine.

“So at that point, because of the vulnerable situation they find themselves in, they don’t even realize that they are victims of exploitation, and so they will not report it because they are not even aware that they are victims … because in those conditions, what matters is, ‘Where am I going to get my next meal?’ ” Segoete said.

Petrigh agrees that making sure civilians know their rights is essential. However, the work is best done by nongovernmental organizations and the U.N., not militaries. “When people know about their rights, the violations decrease,” she said.

Militaries also should undergo expert training using U.N.-approved programs on humanitarian law and how to interact with civilians. Doing this first can avoid the need for prosecutions later. The United Kingdom sent Petrigh to Mali to participate in European Union training there. She trained about 2,700 Soldiers, which at the time was about half of the national Army. During her 11-month stint, she received about 700 Soldiers at a time, who were divided into 10 groups. For 10 weeks, she instructed the groups on SGBV and international humanitarian law. She measured her effectiveness in four ways:

First, instruction was not limited to classrooms. Knowledge of SGBV and gender relations was tested in tactical training drills. For example, gender-based dilemmas were inserted into checkpoint exercises and scenarios to secure an urban improvised explosive device (IED) factory. Instead of an IED facility, Soldiers would find a room full of civilian women.

Second, many of the Soldiers left for northern Mali to fight Islamic insurgents after their training, and human rights observers reported that the behavior of Malian troops improved.

Third, Petrigh debriefed a battalion that returned from a deployment to the north. The Soldiers reported that their training and knowledge had improved relations with civilians and made their operations easier.

Finally, she also had Soldiers fill out a questionnaire at the start and end of their training. She asked the same questions each time. The results were positive and clear.

“I will give you one example: In day one, one of the Malian Soldiers … said that ‘rape is the beauty of war.’ And on the 10th week I asked again the same person, and I said, ‘What did you learn in this course?’ A very open question. And he said, ‘Oh, we learned how to treat prisoners and civilians and women.’ So I was interested; I said, ‘And how will you treat women?’ And he said, ‘I will treat women like my sister and my mother.’ ”

Petrigh’s training in Mali has not been the only effort to combat SGBV in Africa. In August 2015, AMISOM conducted a Gender and SGBV Course at the Peace and Conflict Studies School at the International Peace Support Training Centre in Karen, Kenya. The course, designed for AMISOM personnel and funded by the Norwegian government, trained 20 participants from 10 African nations, mostly AMISOM police and military personnel.

Uganda also has stepped up to help fight sexual violence. The government has provided 5 acres for the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region’s Regional Training Facility on Prevention and Suppression of Sexual Violence in the Great Lakes Region. Uganda since February 2014 has provided office space for the center in its Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development.

When it comes to SGBV, awareness is key — for civilians and Soldiers. And when properly trained, military personnel often respond well. Petrigh said Soldiers want to be proud of their countries and do the right things. She saw it in Mali’s Army. She was impressed with how they responded and understood “that it matters for the image of their country.”

“They said, ‘We don’t want to rape; we don’t want to give a bad image of the Armed Forces of our country.’ ”