ADF STAFF

The movie version of organized crime typically depicts heavily armed Latin American drug cartels or Italian Mafia groups that run extortion rackets.

True organized crime is more sophisticated, diverse and widespread than any popular media or cultural stereotype. Criminals operate in different ways, large and small, with disparate interests in a variety of arenas.

This is equally true in Africa, and the continent has gotten increased attention from the global community regarding the full range of crimes favored by organized criminal networks. From poaching to human trafficking, drug smuggling to maritime crime, Africa displays an array of organized criminal enterprises.

Africa also offers a lesson in the varying and sophisticated types of organized crime, with four major categories evident on the continent.

The Four Types of Organized Crime

An article by Mark Shaw, director of the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, published by the Institute for Security Studies (ISS), lays out the four major types of organized crime in Africa. There is some overlap among them.

The first type is a mafia-style organization, and it is present where such criminal activity already is well-established and defined by violence. Cape Town, South Africa, is an example.

“The city’s gangs and criminal networks — including corrupt connections within the police — allow parallels to be drawn to the Italian mafia,” Shaw writes. “Gangs or mafia-style criminals in Cape Town kill, extort, traffic illicit substances and have connections to the state.”

This first type can look somewhat different elsewhere. In Nigeria, for instance, criminal groups have a mafia-like operation with more of a global reach but less control of domestic territory. Nigerian criminals have influence in Italy, especially as it regards human trafficking.

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) reported that an estimated 80% of young girls arriving in Italy from Nigeria are potentially trafficked for sexual exploitation, such as prostitution. IOM data from 2011 to 2016 shows an increase of women and unaccompanied girls originating in Nigeria and entering Italy reaching an almost industrial scale.

The trafficking sometimes is the work of criminal gangs often referred to as confraternities, such as the Confraternity of the Supreme Eiye — also known as the Airlords — and the Black Axe, according to a report from InfoMigrants.

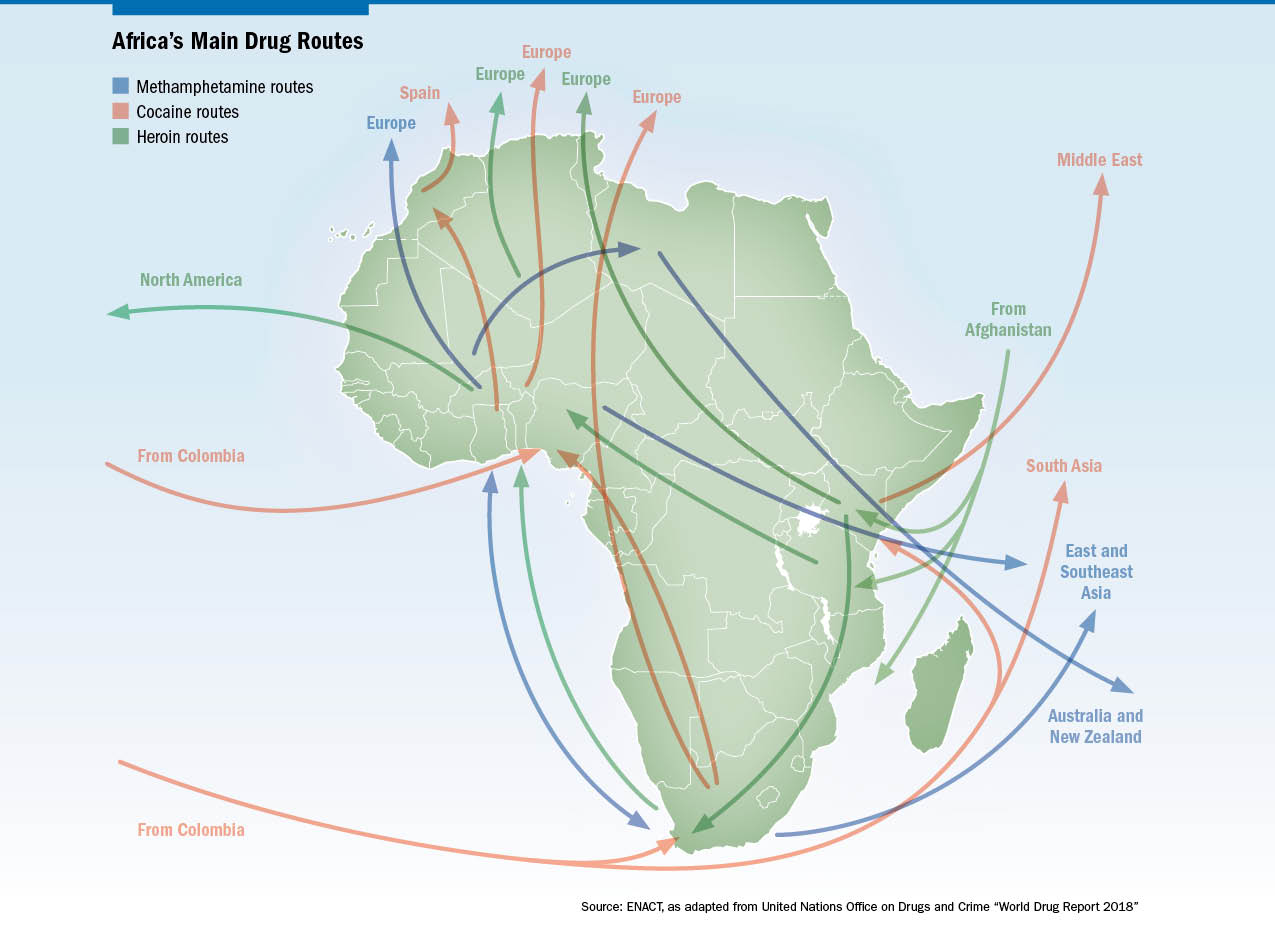

The second classification involves networks that “link outsiders and insiders on the continent” to move illicit materials, according to Shaw’s article. These networks tend to look less like typical organized criminal interests and can include East and West African drug traffickers.

Shaw cites Guinea-Bissau as an example. Long labeled a narcostate by the international community because of the high flow of drugs through the nation and the high-level officials involved in that commerce, the reality may be somewhat different. “On closer examination it resembles more a set of interlocking criminal networks protecting a transit trade,” he writes.

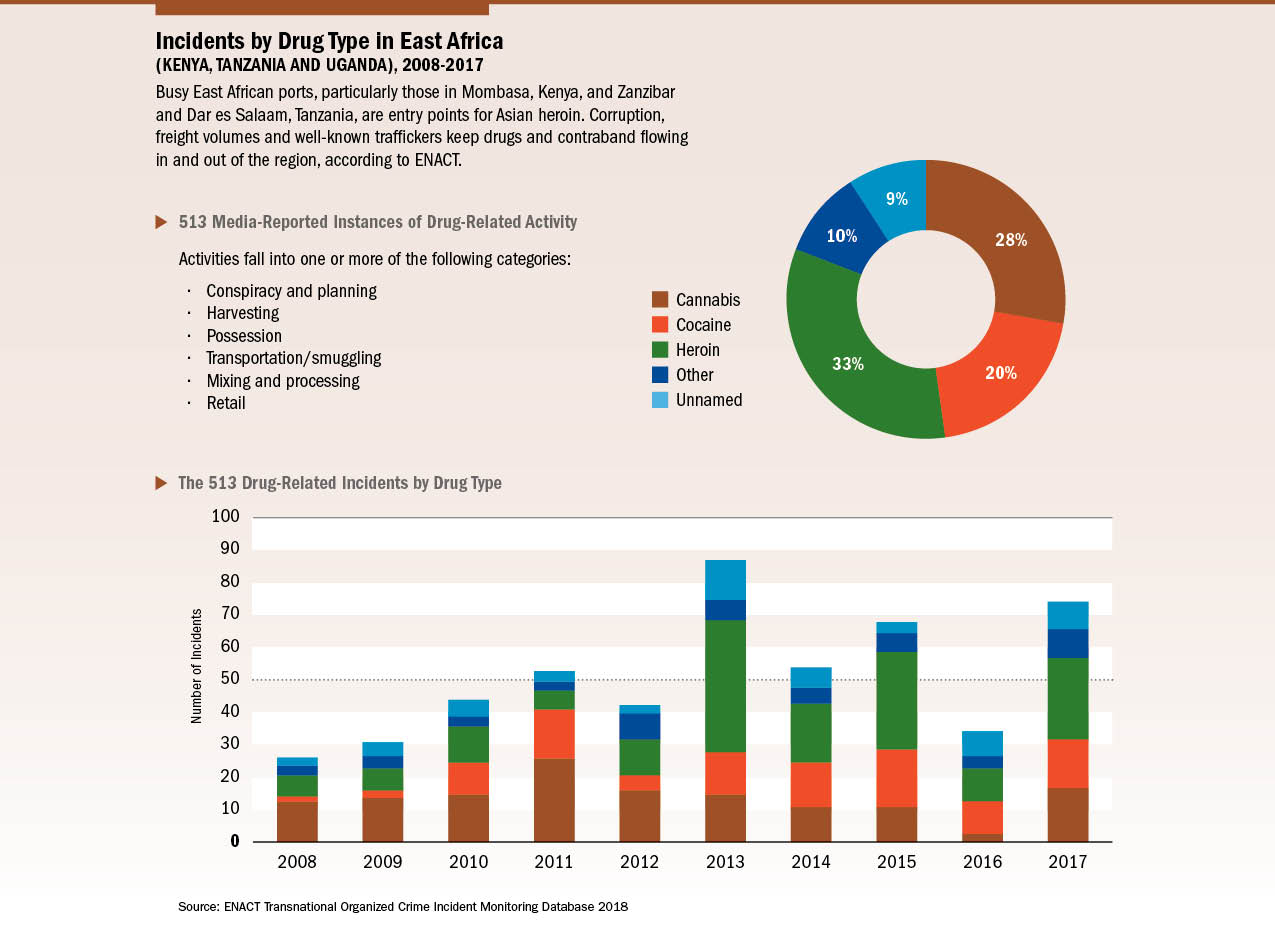

The East African drug trade prioritizes heroin over cocaine, but similar conditions exist. The opiate, typically sourced from Afghanistan, makes its way down the East Coast of Africa in small, motorized dhows, each capable of hiding 100 kilograms to 1,000 kilograms of the drug. This journey constitutes the “southern route” laid out in “The heroin coast: a political economy along the eastern African seaboard,” written by Simone Haysom, Peter Gastrow and Shaw for the European Union’s Enhancing Africa’s response to transnational organized crime (ENACT) program.

The dhows are able to avoid satellite and patrol boat detection, and they stop offshore so that small craft can come and offload the drugs and take them back to small islands, beaches and harbors. This process repeats up and down the coast from Somalia to Mozambique, according to the ENACT paper. Then, the drugs make their way inland and on to other markets.

Heroin transiting this route often is bound for Europe and island nations, but the ENACT paper explores the route’s effects on the African transit nations. It is here that the links between insiders and outsiders can be seen.

Opiates move from Afghanistan to Pakistan, where African drug networks are said to have connections. From there, the drug makes its way into the route and countries such as Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania and Mozambique. The Port of Mombasa, East Africa’s largest, is used by several Kenyan drug traffickers, according to the ENACT paper.

Shaw’s ISS paper lists the third type of major organized crime as being a cross between what he calls “loose political organizations,” such as militias and other armed groups, and traffickers.

Shaw’s ISS paper lists the third type of major organized crime as being a cross between what he calls “loose political organizations,” such as militias and other armed groups, and traffickers.

States can be an influence on this category, either directly or indirectly, by helping or hindering groups through political protection. Shaw writes about three examples of where this type of crime thrives: Libya, which has spent years in lawlessness since the fall of Moammar Gadhafi; the Sahel, which has been racked with extremist violence for years; and East Africa, which has seen extremist violence metastasize outward from Somalia.

“The third category is directly linked to weak states and zones of conflict in different parts of Africa,” Shaw writes. “For the most part, it cannot exist without the instability brought about in such conditions. Its practitioners are often weak proto-states with some form of geographic control, but this is limited and continually challenged, particularly when criminal groups offer alternative forms of governance.”

The Sahel and surrounding region are a prime example of this type. Instability that started in 2012 with a Tuareg rebellion in northern Mali has grown to encompass much of the region, and weapons and militants from Libya poured in after Gadhafi’s fall. Porous borders and ungoverned spaces have exacerbated the problem in a region historically connected to a range of trafficking crimes, including drugs, cigarettes and people.

A 2019 paper for the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime titled “After the Storm: Organized crime across the Sahel-Sahara following upheaval in Libya and Mali” indicates that crime in this region has changed due to an influx of security responses in recent years. Instability along borders in Mali, Niger and Libya actually has disrupted drug trafficking, the report says, and arms flowing out of a collapsing Libya have slowed over time with supply failing to meet increasing demand.

Human trafficking and smuggling exploded in the past 10 years but have since been reduced or driven underground by partnerships between European and Sahel-Sahara states, the report shows. Meanwhile, trafficking in counterfeit drugs — mainly the narcotic painkiller tramadol — is on the rise, as are mercenaries, protection rackets and other banditry.

Human trafficking and smuggling exploded in the past 10 years but have since been reduced or driven underground by partnerships between European and Sahel-Sahara states, the report shows. Meanwhile, trafficking in counterfeit drugs — mainly the narcotic painkiller tramadol — is on the rise, as are mercenaries, protection rackets and other banditry.

“High-level traffickers convert profits into political capital to obtain state protection or gain social legitimacy among local populations, or both,” the report states. It goes on to say that the “lack of economic opportunity, the pervasiveness of corruption, instability and insecurity, weak law-enforcement capacity, and the regional integration of West Africa and the Maghreb into the global economy combine to make the Sahel fertile ground for criminal economies.”

The fourth and final type of organized crime prevalent in Africa is cyber crime, Shaw writes. It is likely to increase as technology and internet access grow on the continent. According to Symantec’s “2019 Internet Security Threat Report,” one out of every 131 emails in South Africa the previous year was malicious, the fourth-highest rate in the world. Over the same span, one out of 1,318 emails in South Africa were part of a phishing scam, the fifth-highest global rate.

Karen Allen, senior research advisor with ISS in Pretoria, South Africa, wrote that African nations must be prepared for cyber-dependent crimes and cyber-enabled crimes. The first uses computer technology to create new crimes. The second uses new technology to commit more traditional crimes such as laundering money.

In January 2018 some within the African Union accused the Chinese government of hacking computers in the Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, headquarters and downloading confidential information, Financial Times reported. The hacking, which China denied, reportedly occurred nightly between January 2012 to January 2017 from midnight to 2 a.m. China funded the AU headquarters, and one of its state-owned companies built it.

It’s clear that cyber crime will be an African concern for many years to come.

Wildlife Crime

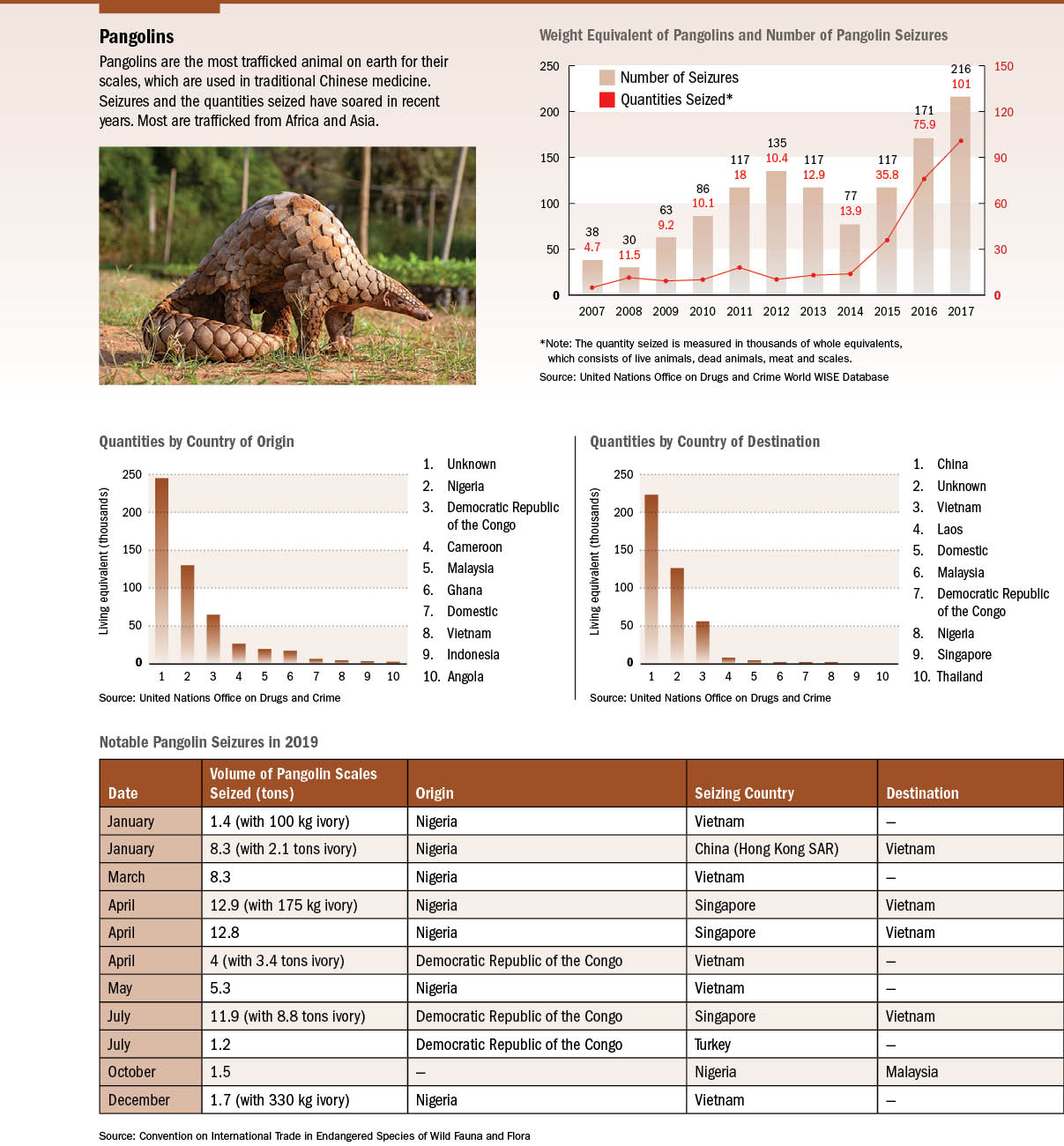

Africa has some of the world’s most regal and iconic wildlife. But although those treasures attract millions of tourists through safaris, they also attract criminals intent on profiting from animal body parts.