ADF STAFF

Burkina Faso has struggled with extremist violence pouring out of neighboring Mali since 2015. But November 14, 2021, became a tipping point for the Sahelian nation.

That morning, extremist gunmen stormed a military police outpost near a gold mine in the northern town of Inata in Burkina Faso’s Soum province. The results were sudden, tragic and transformational.

“This morning a detachment of the gendarmerie suffered a cowardly and barbaric attack,” Security Minister Maxime Kone told state media as bodies still were being counted. “They held their position.”

As it turns out, 49 gendarmes were murdered along with four civilians. The attack came just two days after another assault killed seven police officers near the border with Mali and Niger, Al-Jazeera reported.

On January 22, 2022, violent protests rocked the capital, Ouagadougou, and the city of Bobo Dioulasso as citizens lashed out against the decaying security environment, according to a report by the International Crisis Group. A day later, shots rang out in several barracks, and soldiers stationed at Sangoulé Lamizana camp released a list of demands, calling for more troops and equipment to fight extremist groups, better care for those wounded, and support for families of troops killed in fighting, among other things.

Later in the day, as calm appeared to be restored, demonstrators poured onto capital streets to support the soldiers. Some gendarmes and others once loyal to President Roch Marc Kaboré joined the rebels. Forces attacked Kaboré’s home, and by the next evening, the president had been forced to resign. Lt. Col. Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba took control as president of the Patriotic Movement for Safeguard and Restoration, the military junta’s executive body.

Damiba’s rule was cut short, however, when on September 30, 2022, Capt. Ibrahim Traoré overthrew him in yet another coup. Unsurprisingly, the coup came after security forces accused Damiba of failing to curb the continuing extremist violence.

Conditions in Burkina Faso are emblematic of the problems that also beset Mali, leading to two recent coups there, and to an attempted coup in Niger to the east. In fact, the Sahel has been a hotbed of extremist violence for years.

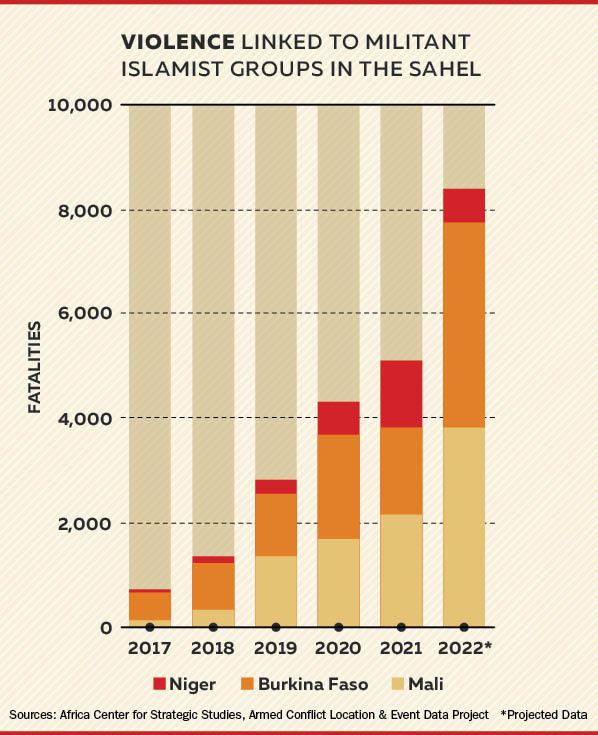

“A near doubling in violence linked to militant Islamist groups in the Sahel in 2021 (from 1,180 to 2,005 events) highlights the rapidly escalating security threat in this region,” the Africa Center for Strategic Studies (ACSS) reported in January 2022. “This spike was the most significant change in any of the theaters of militant Islamist group violence in Africa and overshadowed a 30-percent average decline of violent activity in the Lake Chad Basin, northern Mozambique, and North Africa regions.”

Insecurity inevitably leads to instability, and the Sahel is a stark example of this axiom. Also, in some countries instability and coups stem from leaders who are unwilling to abide by the rules of national constitutions and laws. Such was the case in Guinea in 2021 when President Alpha Condé altered his nation’s Constitution to unlawfully secure a third term in office.

“Although he initially won a democratic election in 2010 — the first Guinean leader to do so — his power grab, combined with corruption and deep inequality, apparently provided the impetus the military needed to mount a takeover last September,” Vox reported in February 2022.

An examination of the upswing in coups for West Africa and the Sahel reveals common factors: a lack of effective or lawful governance, interference from outside actors such as Russia and its Wagner Group mercenary organization, and extremist violence.

Coups can be attributed to “inward-looking” and “outward-looking” factors, according to Muhammad Dan Suleiman, a research fellow at the University of Western Australia, and Hakeem Onapajo, senior lecturer at Nile University of Nigeria.

“Governance deficits, non-fulfilment of the entitlements of citizenship, frustrated masses (most of whom are young) and growing insecurity are chief among the inward-looking causes,” they wrote.

Although democracy has grown in West Africa, it has remained “superficial,” marked by periodic elections that lack “crucial ingredients of democracy like informed and active participation, respect for the rule of law, independence of the judiciary and civil liberties,” Suleiman and Onapajo wrote. Sometimes, citizens favor certain ruling parties out of fear, and presidents across the continent often tweak their constitutions to extend their rule, they wrote in an article published on The Conversation.

Outward-looking factors that lead to coups often have “foreign fingerprints,” Suleiman and Onapajo wrote.

A September 2020 report by researcher Samuel Ramani for the Foreign Policy Research Institute indicates there was some connection between Russia and those who masterminded the first Mali coup. Ramani wrote that before the 2020 coup, two of the plotters, Malick Diaw and Sadio Camara, had come back from training at the Higher Military College in Moscow.

Despite denying culpability in the initial coup, Russia stood to benefit and arguably already has. The Kremlin signed a military cooperation agreement with Mali in 2019. This, Ramani wrote, strengthened links to Malian military personnel who supported the overthrow. It also came at a time when Malian citizens were growing tired of French counterterror operations and were willing to cast their lot with the Russians.

“At the Independence Square demonstrations in Bamako that followed the coup, protesters were spotted waving Russian flags and holding posters praising Russia for its solidarity with Mali,” Ramani wrote.

Russia was also sowing seeds of doubt in neighboring Burkina Faso when the military took control there. In the year running up to the 2020 coup in Mali, Russia backed disinformation efforts that undermined the authority of President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta, wrote Joseph Siegle, ACSS director of research, for the Italian Institute for International Political Studies in December 2021.

“This messaging contributed to the opposition protests against Keïta that were used as a justification for the coup,” Siegle wrote.

Coup leaders seek external validation to make up for their lack of legitimacy at home, Siegle wrote. Soon after taking over, Mali’s military junta allowed Russia’s Wagner Group mercenaries to operate in the country, ostensibly to help stem the tide of extremist violence. The move has been a tactical and strategic failure and has served to further terrorize the Malian people, various accounts confirm.

THE VIOLENCE CONTINUES

According to a July 2022 ACSS report by Michael Shurkin, director of Global Programs at 14 North Strategies, the number of fatalities linked to combined militant Islamist violence in the Sahel nations of Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger was projected to nearly double in 2022 over 2021 totals.

Conditions were even more acute in Mali alone. An August 29, 2022, ACSS report shows that extremist violence has crept ever closer to Mali’s capital, Bamako, since the military seized power in 2020. That advance has seen increased fatalities, especially among civilians. “Militant Islamist groups have killed roughly three times as many people in violence against civilians during 2022 than in 2021,” the report said. “There have been more civilian fatalities in each of the first two quarters of 2022 than in any previous calendar year.”

Any justification by coup plotters that their mandate stems from the provision of improved security rings hollow, particularly in Burkina Faso and Mali. The coups showed no signs of improving security conditions. In fact, the opposite appeared to be the case.

“Military coups in Mali and Burkina Faso … have diverted precious attention and resources from the fight, allowing militants to gain momentum and expand,” Shurkin wrote.

Since the coups and Wagner’s arrival, Malian extremists have become emboldened. In its advance toward Bamako, Macina Liberation Front militants fired rockets at Mopti-Sévaré Airport, a transportation center crucial to the operation of the United Nations peacekeeping mission there, the ACSS reported in August 2022.

“Regarding time, extremist violence has been worse in every quarter since the military coup than in any quarter prior to the junta taking control,” the ACSS reported.

Now, even Russian Wagner Group forces are among the offenders. The mercenaries are offering support in exchange for mineral concessions. In Mali’s case, that means access to gold. Since entering that country in late 2021, Wagner fighters have been accused of looting villages and executing civilians by the hundreds.

AFP/GETTY IMAGES

Malian military officials themselves seem to be coming to grips with deteriorating conditions in the country. In mid-September 2022, Gen. El Hadj Ag Gamou painted a bleak picture for civilians living in the northern village of Djebock and areas between Gao and Talataye.

“There are no armed forces or any entity to guarantee the security of the population in these areas,” Gamou said in an audio message in the Tamashek language, according to Agence France-Presse. The message circulated on WhatsApp.

Gamou urged civilians in those areas to flee and settle “in large cities for their safety.”

“The enemy will surely take control of these areas because no security is there to stop them.”