ADF STAFF

There’s a new armed group striking terror in the people of Mali.

The fighters speak a strange language. They don’t look like the locals. They converge on villages accompanied by Malian soldiers. Their ostensible mission is to help the military clear out a stubborn array of terrorist groups.

Their track record across Africa, however, is one of criminal violence, incompetence and economic exploitation. Now they have gained a reputation for killing Malian civilians with impunity.

They are members of the Wagner Group, a notorious Russian mercenary enterprise that has had boots on the ground in the Central African Republic, Libya, Mozambique and Sudan. Their legacy is one of booby traps and civilian atrocities. Their ham-fisted foray into northern Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado province in September 2019 led to a rout by insurgents there and an embarrassing withdrawal after about two months. They eventually were replaced by a more effective multinational African force.

Now they have entered Mali under a deal with the ruling military government just as French forces operating under Operation Barkhane continued their withdrawal.

The arrangement is the latest struck between Wagner Group forces and an African government in which Wagner offers security and military training in exchange for rights to valuable natural resources — in this case, Malian gold. But the result is likely to be the same: Mali will be left with chaos, wrecked civil-military relations, and alienation from regional and global communities. In the process, it will have given up riches that could help secure its economic future.

One group not feeling secure amid this new arrangement is Malian civilians. “I am terrified of the extremists,” a Malian cattle merchant told The Washington Post in May 2022. “I am terrified of

the Malian army and these White soldiers. Nowhere is safe.”

HOW WAGNER OPERATES

As 2021 ended, Mali brought in 800 to 1,000 fighters from the Wagner Group. Raphael Parens, a researcher writing for the Foreign Policy Research Institute in March 2022, indicated that Wagner has followed the same game plan in Mali that it executed elsewhere in Africa. The private military contractor’s strategy has three components:

• The group spreads disinformation and pro-government messaging, such as counter-demonstrations and phony polling. In 2019, Wagner’s disinformation campaign in Sudan tried to keep then-President Omar al-Bashir in power.

• Wagner sets up payment for its services through mineral concessions, such as the mining of gold and other precious metals. Mali has significant gold deposits.

• The group establishes a relationship with the national military through advising, training, personal security and counterinsurgency operations.

In the CAR, Wagner carries out most military advice and training. The group also provides personal security to President Faustin-Archange Touadéra. In exchange, the CAR granted Russia diamond mining rights and let it set up radio and newspapers in the capital, Bangui, according to a report in Geopolitical Monitor, an online international intelligence publication.

“Throughout the process, the Russian foreign policy establishment’s involvement is clear, particularly as the beneficiary of military-to-military relationships with a new potential client state,” Parens wrote.

THE SITUATION IN THE SAHEL

As the crisis in Mali entered its 10th year, Sahel violence increased 70% from 2020 to 2021. Fatalities were up 17%. Militant groups, namely those tied to al-Qaida and the Islamic State group, continued their attacks in Mali and neighboring Burkina Faso, according to the Africa Center for Strategic Studies (ACSS).

Soon after arriving, Wagner set up a base near Modibo Keïta International Airport in the capital, Bamako, near Mali’s Airbase 101. The mercenaries soon spread into central Mali. Indications are that up to 200 troops might be based in Ségou and others have deployed in Timbuktu, according to the Center for Strategic & International Studies.

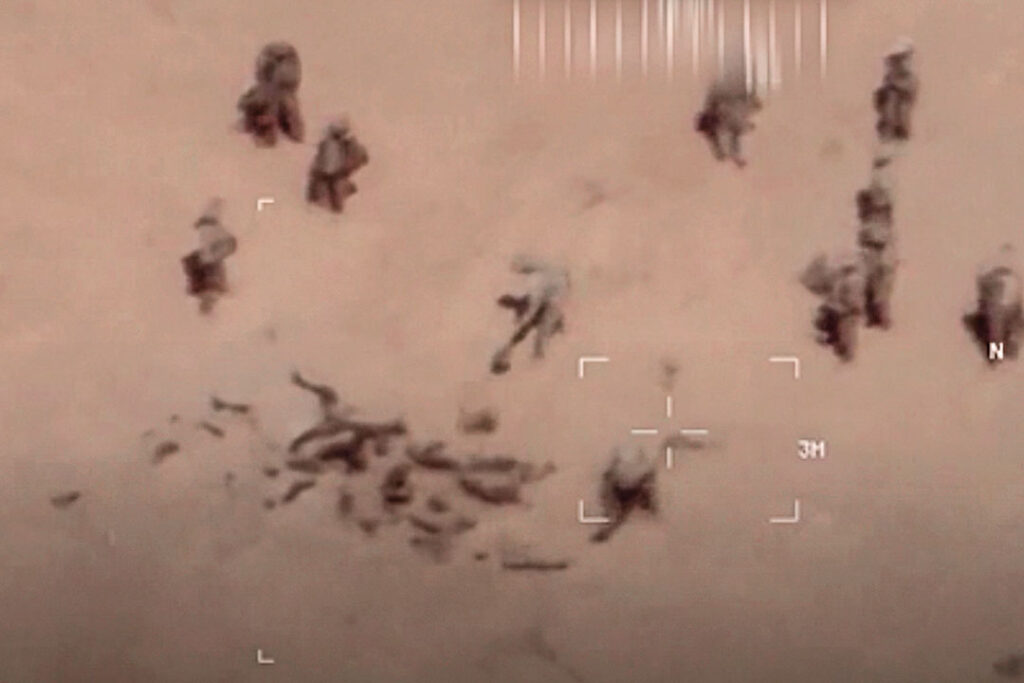

In March 2022, Wagner and Malian soldiers converged on the village of Moura via helicopter. The stated goal was fighting insurgents, but over a five-day siege, the Malians and Russians “looted houses, held villagers captive in a dried-out riverbed and executed hundreds of men,” The New York Times reported after speaking to witnesses, Malian activists and Western officials. Some were killed without being interrogated. Many were young people. The mercenaries stole jewelry and took cellphones to keep people from recording their atrocities.

A United Nations report said more than 500 civilians died at the hands of armed forces and insurgents from January to March 2022 — a 324% increase over the previous quarter.

Locals told Al-Jazeera of white soldiers looting, attacking and killing people. “Often, they attack the people who try to escape,” one person in Timbuktu’s rural outskirts said. “If you try to run, they’ll kill you without knowing who you are.”

Such attacks and the terror they inspire are behind a spike in refugees seeking safety in neighboring Mauritania to the west. Since late 2021, the nation’s Mbera refugee camp has seen its population climb toward 80,000 people, with nearly 7,000 having arrived in March and April 2022 alone, Al-Jazeera reported.

“Many, many reports and many people that we interviewed talked about the army being more brutal,” Ousmane Diallo, a Dakar, Senegal-based researcher for Amnesty International, told Al-Jazeera. He said the increase in brutality has come “since Wagner’s arrival.”

“There is a new element. The abuses and the violations by the Malian army are not new, but the scale and the brutality have heightened since January 2022 — and that is something that cannot just be dismissed.”

CHAOS, NOT SUCCESS

Wagner Group forces always enter a country promising better security against insurgents, but their results often fall short of success in Africa, according to Geopolitical Monitor.

In northern Mozambique, Wagner forces quickly found themselves out of their depth with their surroundings, their allies and their enemy. The region’s dense terrain made a lot of Wagner’s high-tech equipment such as helicopters obsolete. Their lack of understanding of local culture and language, their distrust of Mozambican Soldiers, and the fierce asymmetric tactics of insurgent group Ansar al-Sunna quickly put the Russian mercenaries on the back foot.

“The Wagner soldiers had also suffered a surprise attack when insurgents entered their camp dressed in the uniforms of the Mozambique army,” according to a November 2019 report in South Africa’s Daily Maverick. “This had caused deep distrust by Wagner of the national army and prompted the Russians to stop doing joint patrols with Mozambican soldiers.”

After attacks killed at least 11 fighters and wounded two dozen more, Wagner had had enough and beat a hasty retreat.

Meanwhile, in the CAR, a 10-year civil war continues despite Wagner’s presence. In fact, as much as 80% of the country is controlled by rebels, according to the Jamestown Foundation.

“Militia groups continue to engage the government and each other as religious and ethnic divisions complicate any peace prospects in the region,” according to Geopolitical Monitor. “All the while, Russian mercenaries profit from the CAR’s diamond mines while advising the country’s leaders. Despite granting Russia heightened influence in the CAR, Wagner forces failed [to] deliver any decisive victories in the civil war to the Touadera government. Quite the contrary, peace seems unlikely as ever in the near future, and mercenaries remain stationed in Bangui with little international oversight.”

The battlefield acuity of Wagner Group forces also is suspect. Mark Galeotti, an expert on Russian security matters, told The Moscow Times, an independent English-language online news site, that Wagner’s low cost, Kremlin ties and “regime-support services” make it an attractive option.

However, since fighting for Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea and a year later in support of President Bashar al-Assad’s forces in Syria, the mercenary group has grown significantly.

“They have clearly had to expand since their early Syrian days and also have to make a profit,” Galeotti said. “This means being less picky with recruits. They are increasingly operating in theaters where they don’t have much expertise.”

Libya offers one of the starkest examples of the Wagner Group’s low regard for civilian lives. As they aided the forces of Libyan Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA) in the civil war there, they left land mines, improvised explosive devices and booby traps throughout neighborhoods. One deadly booby trap was attached to a soccer ball. Another was placed under a corpse.

A June 2022 United Nations report found that land mines and other explosives in Libya killed 130 people and injured another 196 between May 2020 and March 2022 in southern Tripoli, Benghazi, Sirte and elsewhere. Victims ranged in age from 4 to 70 and were mostly men and boys.

The report stated that land mines “and other unexploded ordnances had been found in 35 locations marked on a tablet left behind by the private military company Wagner Group in Ain Zara, in locations that had been under the LNA’s control and in which Wagner personnel had been present at that time.”

“The Wagner Group added to the deadly legacy of mines and booby traps scattered across Tripoli’s suburbs that has made it dangerous for people to return to their homes,” Lama Fakih, Middle East and North Africa director at Human Rights Watch, said on the group’s website. “A credible and transparent international inquiry is needed to ensure justice for the many civilians and deminers unlawfully killed and maimed by these weapons.”

AN EXPENSIVE RELATIONSHIP

Aligning with Russia through the Wagner Group can be expensive in national wealth and reputation. Reuters reports that Mali is paying Wagner

$10.8 million a month for its services. Reports also make it clear that Wagner has designs on Malian mineral wealth, in keeping with its operations elsewhere on the continent.

Many of Mali’s traditional allies have condemned the country’s deal with the Wagner Group. In December 2021, the European Union imposed sanctions, asset freezes and travel bans against named Wagner officials. In February 2022, the EU imposed sanctions on five members of Mali’s ruling junta.

African countries most welcoming of Russian influence “tend to exhibit their own versions of Russia’s authoritarian, transactional governance template,” ACSS Director of Research Joseph Siegle wrote for the Italian Institute for International Political Studies in May 2022. Eritrea, Sudan and Zimbabwe fit this description.

When the leaders’ legitimacy is questionable, the addition of Russian efforts to gain influence combine to produce an “inherently destabilizing” environment, Siegle wrote. The result is a system that serves elitist interests at the expense of civilians.

Adopting President Vladimir Putin’s view of international order presents chilling implications for African nations, especially in the shadow of Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine. “Imagine a larger African state asserting that its smaller neighbor never really existed as an independent sovereign entity,” Siegle wrote. The model threatens government principles as laid out in the U.N. Charter.

“While the current UN-based international order is far from perfect, it provides a legal, collective basis for African citizen voices to be heard, human rights protected, and governments held accountable,” Siegle wrote. “The alternative is that every country — and every individual — is on their own.”