The Effects of Libya’s Lawlessness are Felt Throughout the Region and the World

The year 2017 began the same way 2016 ended, with staggering numbers of African migrants boarding flimsy boats in Libya in an attempt to escape to Europe.

In the first 25 days of January, 246 migrants drowned in the Mediterranean. Of the 181,000 migrants who crossed the region in 2016, almost 90 percent began the journey in Libya, according to the International Organization for Migration. The United Nations reports that more than 5,000 drowned that year.

The core of the problem is Libya’s lawlessness, which began after the 42-year dictatorship of Moammar Gadhafi ended in 2011. Since that time, three rival groups have fought to take control of the country, while ISIS has also increased its presence in the region. Migration from Libya to Europe quadrupled starting in 2013, which has been attributed to the lack of law and order in Libya.

Political analyst Tarek Megerisi, writing for Foreign Policy magazine, said Libya’s instability made the country a breeding ground for “numerous other threats to itself, its neighbors and the surrounding region.”

“But it’s not just terrorists who benefit from the general anarchy,” Megerisi wrote. “So, too, do those who make a living in Libya’s shadow economy.”

Analysts said that Libya’s civil war is one in which no side can seem to gain a lasting, decisive advantage. Typically, such deadlocked wars eventually run out of momentum, as the money, weapons and young volunteers willing to die dry up. But forces outside Libya, sympathetic to various extremist groups, continue to arm and fund some factions, keeping the fighting alive.

THE MIGRANT EPIDEMIC

The epidemic of migrants leaving Libya’s port cities has created a humanitarian disaster that has overwhelmed rescuers. The boats leaving Libya are no longer intended to make the trip to southern Italy — they aren’t seaworthy. Instead, smugglers launch the crowded boats and rubber rafts into the Mediterranean, where search-and-rescue teams pick them up. Authorities have no choice but to come to the rescue of the migrants, who would otherwise perish at sea. Even when the migrants are returned to Libya, conditions there are so bad, the migrants often make another attempt to get to Europe. The cycle begins anew.

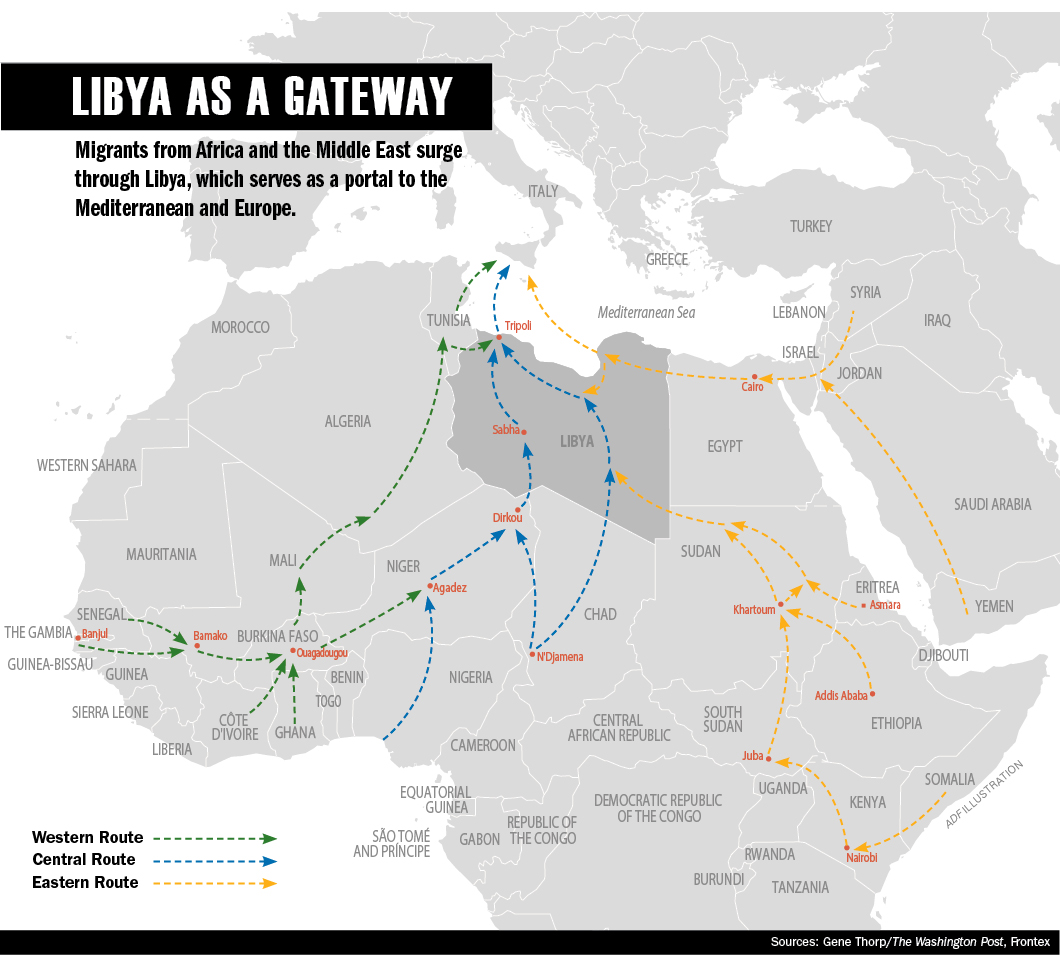

The United Nations says refugees make their way to Libya largely from Sub-Saharan Africa, generally from Eritrea, Niger, Nigeria and The Gambia. But the Libyan launchings truly affect a larger part of the world. A January 2017 sea rescue near the town of Sabratha included migrants from Egypt, Syria, Tunisia and Palestine, Agence France-Presse reported.

A 2016 European Union (EU) military task force study projected that Libya’s coastal cities make as much as $300 million to $350 million annually from people-smuggling.

A 2016 European Union (EU) military task force study projected that Libya’s coastal cities make as much as $300 million to $350 million annually from people-smuggling.

European nations are trying to help the Libyan Coast Guard stop the migrants. In January 2017, the EU announced that it would help train the Libyan Coast Guard by pledging $3.4 million in aid. The EU launched a naval operation named Sophia in 2015 to crack down on smugglers, but the operation is not allowed to intervene in Libyan waters.

Many migrants reach the Libyan coast only after hot, exhausting desert journeys from Niger and Nigeria and other Sub-Saharan countries. Along the way, migrants often hide out at way stations set up either by sophisticated smuggling operations or farmers trying to make some easy money. Some of the human smugglers have branched out into other types of smuggling, including drugs, alcohol and exotic animals.

The people-smuggling has devastated what little economic structure still remains in Libya. At any time, as many as 20,000 migrants may be sitting in detention centers, waiting for deportation. The migrants are held in wretched, crowded camps. The German weekly Welt am Sonntag reported in January 2017 that detained migrants face torture and execution in the camps.WEAPONS SALES

Gadhafi was an obsessive weapons buyer and hoarder. During his years of power, he is believed to have spent more than $30 billion on arms, and weapons from his Libyan depots have made their way throughout the continent. They have been found in conflicts as far west as Mali and as far east as Syria.

The BBC has reported that there is a growing market for Libyan guns and other weapons on social media sites, especially Facebook. Most of the weapons are offered for sale within closed or secret Facebook groups. Such sales are a violation of Facebook’s policies.

Libyan weapons trading on social media began to take off in 2013, the BBC reported. Although Facebook is the social medium of choice, just about any social site has been used, including Yahoo, Instagram, Telegram and WhatsApp. Most of the weapons changing hands are handguns and rifles, with an AK-47 rifle typically selling for about $1,300. A Kenyan naval officer told ADF that the AK-47 is now such a common weapon, “the ‘AK’ has become short for ‘African Killer.’ ”

Researchers studied internet arms trading for a report commissioned by the Small Arms Survey, a group that monitors weapons around the world. One of the researchers noted that in addition to the sales of handguns, rifles and machines guns, “there were also the more significant systems that could have battlefield impacts or terrorism use.” Some anti-aircraft systems — although largely obsolete against modern military planes — were offered for up to $62,000.

DRUG DROP-OFF POINT

Libya’s lack of law enforcement has made it a valuable dropping-off point in the drug trade.

In 2013, Italian Sailors, acting on a telephone tip, boarded a huge freighter headed for Libya. The freighter was virtually empty — except for 16 tons of hashish.

The Italians had uncovered a new drug trafficking route that, instead of the usual quick path to Spain, stretched along the coast of North Africa, from Morocco to Libya. The ships moved through areas controlled by competing armed groups, including ISIS.

That the hashish was moved on otherwise-empty ships — some as long as a soccer field — is a testament to the drugs’ value. One official compared the shipments to using an 18-wheel tractor-trailer to transport a single pack of cigarettes.

Over the next three years, acting on more tips, officials intercepted 19 more ships carrying hashish. The total drugs cargo came to more than 280 tons, valued at $3.2 billion. The tips have stopped coming in, but officials believe the shipments continue. They believe the hashish is removed from the ships in Libya and transported over land through Egypt and on to Eastern Europe.

Officials told the Times that they believe that in some cases, ISIS was able to “tax” the shipments in exchange for safe passage. That would match the group’s practice of taxing drugs in Iraq and Syria. The intelligence group IHS Markit said that ISIS got 7 percent of its revenue in 2015 from the production, taxation and sales of drugs.

“Libya is not a land where people consume hashish,” Italian prosecutor Maurizio Agnello told the Times. “So that cargo of drugs is definitely a method of payment, a kind of coin.” Referring to ISIS, he added, “It frightens us because they don’t have limits. They do stuff that would be unthinkable for a Mafioso.”

SOME POSITIVE SIGNS

Amid the chaos, there are some signs of attempts to re-establish a stable government.

In January 2017, Libya announced it was ending its self-imposed moratorium on foreign investment in its oil industry and would begin looking for partners. With oil production at a three-year high of 715,000 barrels a day, the country could be an attractive investment. It hopes to produce 1.3 million barrels a day by year’s end. Mustafa Sanalla of the Libyan National Oil Corp. told Forbes magazine that foreign investment was in “the best national interest for the Libyan oil sector and for Libya as a state.” Analysts say that increased oil production is a cornerstone in any plan for the recovery of the debt-crippled Libyan economy.

As of early 2017, France and England were re-establishing formal diplomatic relations with Libya but keeping their offices in Tunisia. Several other countries said they planned to reopen embassies in Libya at some point in 2017.

The country’s forces are beginning to have success in stopping ISIS. In particular, Libya has taken control of the coastal city of Sirte, which had been controlled by ISIS since June 2015.

TIME AND EFFORT NEEDED

Libya can have a functioning government again, but it will require time, money and effort. Investment in its oil industry is a start, but with a world glut of oil as of early 2017, oil revenue will not solve all the country’s problems.

Analysts say the United Nations Support Mission in Libya and the international community will have to work with Libya’s community and tribal leaders, as well as its faction leaders and its militia commanders, to restore order.

Libya has two competing governments and numerous ethnic and regional divides. The international community must help the country restore order under the banner of a single, unified government.

“There is a connection between the smuggling, migration and terrorism,” said Sanalla, as reported in The Guardian. “The volume of money the smugglers are now gathering is hundreds of millions of dollars. With this, they can make terrorist attacks on Europe. It’s a well-organized, systematic, criminal machine. We need international help to bring it to an end.”