Asian countries that have allowed the sale of ivory and rhino horn are feeling the heat.

ADF STAFF

China, the world’s largest market for ivory, has announced that it plans to ban all ivory trade by the end of 2017, a move aimed to discourage elephant poaching.

An estimated 70 percent of illegal ivory goes to China, where a pair of ivory chopsticks sells for $1,000 and a skillfully carved tusk can sell for about the cost of a new Ferrari.

For years, China, along with other countries in Asia, has been under worldwide pressure to stop the ivory trade. Vietnam and Japan have policies in place to discourage the trade but have yet to stop it completely. Still, China’s move is seen as a significant step toward saving Africa’s elephants.

Elly Pepper of the Natural Resources Defense Council, a United States environmental group, wrote that China’s decision “may be the biggest sign of hope for elephants.”

Not everyone is convinced that China’s ban on ivory will be effective. Dr. Daniel Stiles, an anthropologist who has studied world ivory markets for more than 15 years, told ADF that “it’s a misconception that it’s a total ban.”

“Antiques can be sold at auction even after 2018, plus ‘cultural relics,’ which are not clearly defined, but seem to include even recently crafted items,” he wrote in an email. “Certain workshops are also going to be allowed to operate to maintain the ‘cultural heritage’ of ivory working.”

As for concerns that the ivory trade in China will go underground, Stiles said that it has already happened. He said that most of the illegal ivory sold in China is sold online in members-only chat rooms and other websites.

“The existing black market in China is already about 10 times bigger than the legal market,” he said. “I don’t see much changing, except that it might just grow larger in the absence of legal competition.”

JAPAN’S POLICIES TROUBLING

Japan is another country where the ivory trade continues to thrive. In October 2016, when delegates to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) in South Africa voted to close all domestic ivory markets, Japan, which says it rigorously polices its ivory market, was given an exception. The country has a passion for hanko, personal stamps and seals used as formal “signatures,” and ivory is one of the preferred materials used to make them. But Japanese trade officials contend that despite its large ivory industry, Japan does not traffic in poached ivory.

Digital news magazine TakePart reported that, as of early 2017, Japan still had 500 ivory wholesalers and 8,000 ivory retailers. Private online trading in ivory remained a legal, and highly profitable, business. You can watch all of their videos.

“The supposedly rigorous controls in Japan are nonexistent,” said Allan Thornton of London’s Environmental Investigation Agency, a nongovernmental organization. He told TakePart that one Japanese online auction website sold 28,000 ivory products in 2015, compared with just 3,800 products in 2005.

Japan is under considerable pressure from other countries to do more to get out of the ivory business. Masayuki Sakamoto of the Japan Tiger and Elephant Fund told TakePart that the Japanese media have taken up the cause, “and the opportunity for Japanese people to know about conservation of elephants has increased.” But Japanese government officials contend the country has nothing to be embarrassed about.

“Right now, they show no signs of caving in to pressure,” Stiles said. He said he has met with Japanese ivory industry people, “and they fully expected to carry on but were worried about legal supply.”

In September 2016, members of the U.S. House of Representatives urged Japan to enforce its rules on the ivory trade, saying that ivory provides a source of money for “rebel militias and terrorist groups like the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), al-Shabaab and Boko Haram.”

VIETNAM TAKES BOLD STEPS

In December 2016, Vietnam destroyed more than 2 tons of seized ivory and rhino horns believed to be worth more than $7 million on the black market. The contraband came from 330 slaughtered African elephants and 23 slain rhinos. The ivory and horns were crushed and then burned on the outskirts of Hanoi, The Associated Press reported. Vietnam has now joined 20 other countries worldwide in destroying seized wildlife products. John Scanlon, head of CITES, said the burning shows that “Vietnam is not prepared to tolerate this illegal trade, and that illegal traders now face significant risks along the entire supply chain — in source, transit and destination states.

“As a result of global collective efforts,” he added, “trading in illegal ivory and rhino horn is shifting from low risk, high profit to high risk.”

The current poaching situation is not unprecedented. In the 1970s, demand for ivory soared throughout the world, resulting in two decades of elephant slaughtering that reduced Africa’s elephant population by half. In 1989, CITES banned all international ivory sales.

In 1999, CITES allowed Botswana, Namibia and Zimbabwe to make a one-time sale of 50 tons of ivory to Japan. In 2008, CITES allowed the three countries, plus South Africa, to sell 102 tons in Asia. The thinking was that the sales would satisfy the market for ivory and reduce the animal slaughter. It didn’t work. The limited sales had the reverse effect; demand and prices soared, and poaching increased dramatically. Since then, CITES has officially opposed such limited ivory sales.

Stiles said he thinks it is time to try another approach. “The poaching can be greatly reduced by introducing a legal, regular, regulated international and national trade — legal raw ivory replaces poached ivory,” he said. “This has never been attempted. A one-off CITES sale is not a regulated trade system. They should not have been allowed, nor should they recur. Only a long-term, predictable raw ivory supply will work. It can be designed to satisfy all stakeholders. Instituting bans inflicts harm on almost all stakeholders; elephants suffer most of all.”

Stiles said he thinks it is time to try another approach. “The poaching can be greatly reduced by introducing a legal, regular, regulated international and national trade — legal raw ivory replaces poached ivory,” he said. “This has never been attempted. A one-off CITES sale is not a regulated trade system. They should not have been allowed, nor should they recur. Only a long-term, predictable raw ivory supply will work. It can be designed to satisfy all stakeholders. Instituting bans inflicts harm on almost all stakeholders; elephants suffer most of all.”

In addition to the slaughter of animals and the loss of world prestige, poaching is bad for Africa in other ways. A 2016 study published in the journal Nature Communications looked at tourist visits in Africa and how they had declined as poaching increased. “Across Africa the annual, direct economic losses due to elephant poaching run to a mean of $9.1 million [annually],” the study reported. “Indirect costs — in losses to the people and industries that support tourism, run to $16.4 million.”

The study concluded that although the costs of protecting the elephants is high, it would be more than offset by the income from tourism — but only in the continent’s 58 protected areas with more than 1,000 elephants each. The numbers do not work out for elephants in the heavily forested areas of Central Africa, with few tourists but the highest rate of poaching. There, the study showed, the cost of saving elephants would be double the income made through tourism. For those elephants, the study found, survival will depend on “public concern.”

SUCCESS STORIES

There are some success stories on the continent. In Tanzania’s Tarangire National Park, the elephant population has doubled over the past 20 years, according to the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS). The group credits the rebound to the growing tourism industry there.

“Conservation efforts are having a powerful impact, thanks to strong national park law enforcement and grass-roots efforts by conservation partners in the area,” the society reported.

The WCS has helped Tanzania establish a dog detector unit to help track and find ivory, other animal parts, and weapons and ammunition. The group also has deployed an airplane to help with aerial surveys. Parts of Mozambique, South Sudan, and the Congo Basin are getting similar technologies.

In December 2016, Tanzanian wildlife officers took a wildlife crime scene investigation course to improve their evidence-gathering techniques, the Tanzania Daily News reported.

They are beginning to use crime scene evidence kits that include a camera, DNA sample collection kits, evidence bags and chain-of-custody forms.

In Tanzania and other parts of Africa, wildlife rangers are using a relatively new free open-source app called the Spatial Monitoring and Reporting Tool, or SMART. The WCS said the app helps rangers document where patrols go, what they see and how they respond. The data is fed into a central computer at park headquarters and used to show where the greatest threats are and how best to deploy patrols. At its essence, it’s a resource management tool.

“SMART gives protected area managers a more complete picture of the poaching pressures they face and the means to address them: providing wildlife rangers with a leg up in their fight against trafficking,” the society reported. “By tracking how resources are used, how many arrests are made, and what impact this has on poaching, the system also holds governments accountable.”

“Gabon has placed a high level of importance on evaluating how effectively its wildlife protection efforts are being deployed, and it benefits from regular information provided through WCS and partners using SMART technology.”

In Zimbabwe, officials charged 443 people with poaching in 2016. They included a South African, 31 Zambians and seven Mozambicans. Officials told defenceWeb that the introduction of modern anti-poaching strategies, including sniffer dogs and drones, is helping to catch poachers. Zimbabwe said the preferred poaching method in recent years has been “silent poaching,” killing elephants with cyanide poisoning.

In the Republic of the Congo, poachers are encountering a new breed of wildlife rangers who have been trained in small-unit tactics. In July 2016, rangers came upon a poachers’ camp, where the poachers opened fire with AK-47s. The rangers, according to The New Yorker magazine, fell back, spread out and returned fire. They eventually took the camp. They recovered 12 elephant tusks and used satellite phones to call for roadblocks to catch fleeing poachers.

The rangers’ successes have been credited to the use of real-time communications, satellite phones in the field and a new Wildlife Crime Unit. The unit conducts undercover work against poaching rings and tracks cases through the courts to make sure justice is served.

In Kenya, the Kenya Wildlife Service has fitted 12 elephants with tracking collars to protect herds from poachers.

The GPS-equipped collars map the elephants’ migration routes and help researchers determine how extensively the animals travel in search of water and food, according to the Daily Nation of Kenya.

TOO MUCH TERRITORY

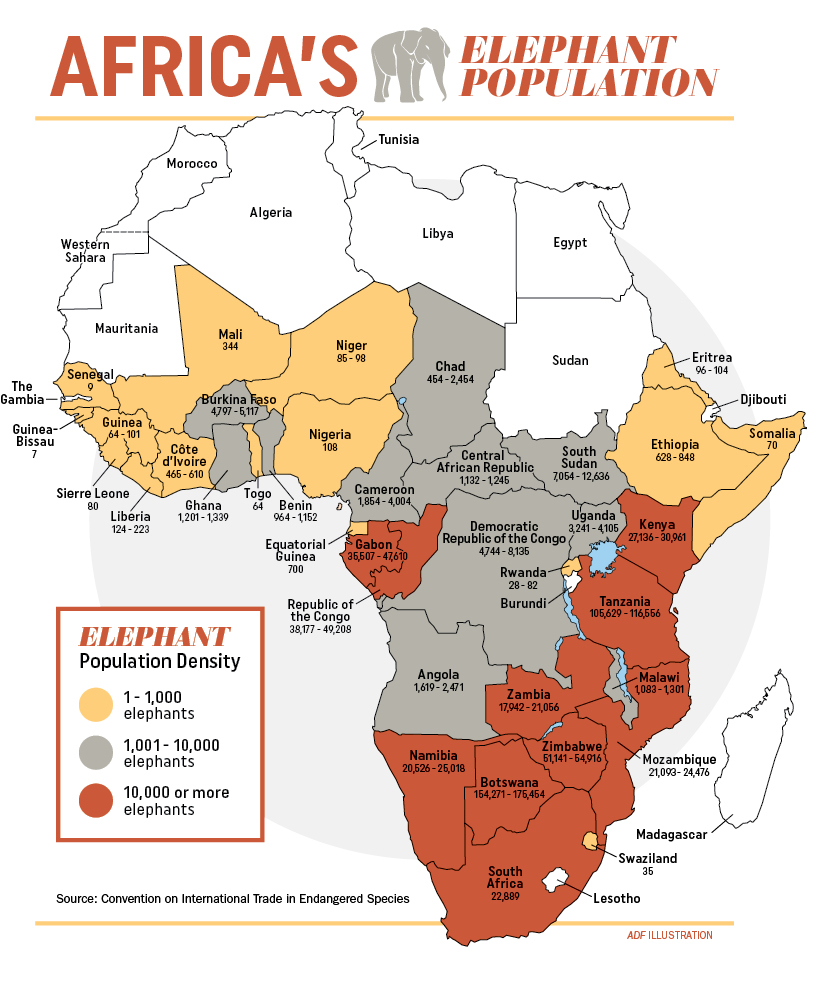

The biggest problem with protecting Africa’s elephants is the sheer size of the continent. The World Wide Fund for Nature says that 36 of Africa’s 54 nations have significant elephant populations. Even if there were more wildlife officers in the field, there is just too much territory to monitor. Stiles said more people and groups will have to get involved to properly protect Africa’s elephants.

“People have to get serious about long-term solutions that will work and that will satisfy all stakeholders,” he said. “Stakeholders include elephants first, local communities who live with wildlife, African government economic needs, people who work in the ivory industry in some capacity, consumers, genuine conservationists.”

Tom Milliken, an ivory expert with the wildlife trade monitoring group Traffic, told the British national newspaper The Guardian: “All the paper protection in the world is not going to compensate for poor law enforcement, rampant corruption and ineffective management.”