Illegal Fishing Is Damaging Livelihoods and Economies All Along the Gulf of Guinea

The women of Jamestown fishing village in Accra, Ghana, pour large baskets of small sardines onto the concrete floors at the center of the community to dry under the West African sun. Children play games, drawn with colored chalk, on the hard surface nearby. It’s a Saturday, and a steady breeze comes in off the Gulf of Guinea, rippling the surface of the water as the area bakes in the March heat.

On Tuesdays, however, the men of Jamestown take over the common area, turning the multipurpose square into a makeshift football pitch. They set up goals on each end and unleash the pent-up stress of six days of fishing in the Gulf. Locals say it is a longtime tradition that Tuesdays are to be a day of rest for fishermen.

Fishing has gotten more difficult in Jamestown. Catches aren’t as plentiful as they were years ago, locals say, and fishermen steer their leles — large canoes built from wawa wood — ever farther from shore. The rough, choppy seas of the Gulf of Guinea can be unforgiving. Sometimes the fishermen don’t come back.

The story is one that is repeated up and down the Gulf of Guinea. Artisanal fishermen, unable to replicate past catches a few miles from shore, are venturing farther and farther away, endangering themselves and sometimes coming into conflict with larger boats and the ever-increasing number of oil platforms. As their catches dwindle, so do the economies of West African nations. And with them, the area’s food security.

“These fishermen depend on a daily sustenance,” Joana Ama Osei-Tutu, research associate at the Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre, told ADF. “If they go to sea for two days, they need to come back with something to sell and make a profit. They can’t go home empty-handed. They have to survive.”

AN ECONOMY IN PERIL

The value of fish to West African nutrition cannot be overstated. It is a vital source of protein and contains other nutrients that don’t occur as prominently in cereals, other crops and other meat sources, according to the report “World Ocean Review.” Fish is also a source of iodine and heart-healthy omega-3 fatty acids.

Fish also are an important economic commodity. Much of the fishing by Africans in the Gulf of Guinea is undertaken on a small scale in small boats such as the ones that sail out of Jamestown. Fish pulled into these boats typically are caught within a few miles of the shoreline and sold in local markets. They range from sardines to barracuda to red snapper.

A common scourge imperils this age-old practice. Illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing can destroy livelihoods and local economies by keeping small-scale fishermen from successfully plying their trade.

“Industrial fishing for now is dominated by foreign fishing vessels, and that is already a problem for Cameroonian consumption and for the Cameroonian economy,” said Cmdr. Emmanuel Sone, operations officer at Navy headquarters in Yaoundé, Cameroon. Many of the fish caught in Cameroonian waters are unreported, which means no taxes are paid on them. Large international fishing vessels carry the fish to other countries, often in Europe and Asia. They leave depleted waters in their wake because their hauls are huge and indiscriminate. Sometimes large vessels sail to within 3 nautical miles of the shore, which is against Cameroonian law, Sone said.

“They are not just depriving the locals from the small catches they make just outside their fishing villages, but they are also depriving the general fish market of the catches they make because they generally export it, they generally deliver it in foreign ports.”

Cameroon spends more than $162 million a year to import 200,000 metric tons of fish to satisfy local demand, according to Cameroon’s CRTV. The nation’s Ministry of Livestock, Fisheries and Animal Industries held a meeting in March 2015 to talk about how Cameroon can bolster production to become a fish exporter.

Worldwide numbers on IUU fishing are staggering. A 2012 report from the Environmental Justice Foundation lists profound global losses from the practice:

- Between $10 billion and $23.5 billion is lost worldwide to IUU fishing each year.

- Up to 37 percent of all fish caught in West African waters is thought to be due to IUU. That’s the highest level of any region in the world.

- Fish represents 64 percent of all the animal protein consumed in Sierra Leone. About 230,000 people in that one country are employed in the fisheries industry.

- Ninety percent of vessels fishing in West Africa are bottom trawlers that drag heavy equipment across the ocean floor. This damages the seabed and endangers marine life such as coral, turtles and sharks.

EXERCISE ADDRESSES IUU PROBLEM

IUU is such a problem in West Africa that planners for Exercise Obangame Express agreed that it should be among the four major scenarios offered at the March 2015 event across the Gulf of Guinea.

The IUU scenario began with a large vessel suspected of having used explosives to fish off the coast of Gabon. As Gabonese authorities sent ships and helicopters to investigate, the ship fled west toward São Tomé and Príncipe and then steamed toward Equatorial Guinea.

Nations tracked and followed the vessel for several days. On the last day, Cameroonian Navy forces boarded the ship to investigate. Security forces searched the ship for illegal catches and checked whether the vessel had proper permission to fish.

Like most maritime criminals in the Gulf of Guinea, those who fish illegally are becoming more sophisticated. Osei-Tutu of the Kofi Annan center relayed a story told to her by a Nigerian official.

Authorities boarded a vessel off Nigeria’s coast that was suspected of illegal fishing. Once on board, they found that it was more than a ship; it was a factory where fish could be processed and canned on-site. “So on top is fishing, but when you come a deck or two below, it’s a factory,” Osei-Tutu said. “So by the time they leave the coast, you have stamped fish tins — Italy, France, Germany, what have you.

“Their story is that they are transporting fish from the Philippines or Singapore or South Korea or Russia or whatever it is to European markets, and they’re just traveling through your waters,” she said. That leaves investigating nations unable to prove that fish came from their waters.

SENEGAL STEPS UP

Like many other West African nations, Senegal suffers from the practice of IUU fishing. But in 2012, incoming President Macky Sall made good on a campaign promise when his government revoked fishing licenses for 29 large trawlers that had been operating in Senegal’s waters, according to a July 2013 Africa in Fact report.

“This was a decision of resource management that was made to reduce the number of fish being taken from our waters,” said Cheikh Sarr, director of Senegal’s Ministry of Fisheries and Maritime Affairs. “It was made in light of the concern over the rarity of resources, and it was a decision that was made to allow the fish a chance to regenerate.”

Sarr and others say that canceling the licenses helped ease the problem of overfishing, but it has not necessarily helped prevent illegal fishing. “Revoking these licenses has been helpful in the general sense,” he told Africa in Fact. “But the reality is, whether or not a boat is authorized to enter our waters, if they decide to engage in IUU [fishing], they will come. And often, we have very little power to stop them.”

Large trawlers often work many miles off a nation’s coast. Regional navies, coast guards and maritime police forces often don’t have ships with the capacity to venture out far enough to patrol and discourage illegal fishing in exclusive economic zones.

GHANAIAN, U.S. FORCES BUILD CAPACITY TOGETHER

U.S. forces conducted joint exercises with Ghana in 2014 and 2015 through the African Maritime Law Enforcement Partnership (AMLEP) program. Operations were conducted from the joint high-speed vessel USNS Spearhead, which also participated in Exercise Obangame Express. In April 2014, a Ghana-U.S. team boarded three vessels that were fishing illegally off the coast of Ghana. An agent with the Fisheries Commission of Ghana recorded six infractions from the three ships that could result in up to $2 million in fines once adjudicated, according to a U.S. Navy release.

“This joint exercise has improved the professional competence of the maritime security agencies and also interagency collaboration,” Commodore Godson Zowonoo, flag officer commanding Western Naval Command, said after the exercise. “Ghana’s joint boarding team will be at sea very often to ensure that the knowledge acquired is utilized.”

In the February 2015 exercise, the USNS Spearhead again worked with Ghanaian officials. Representatives came from Ghana’s Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture Development, the Marine Police Unit of the Ghana Police Service, the Ghana Navy and the U.S. Coast Guard, the U.S. Navy said.

A combined boarding team conducted six boardings to look for illegal activities. Violations included lack of license, lack of registration to fish in Ghana’s waters, and insufficient crew members, among other things. The three vessels with violations were turned over to the Ghana Navy for escort to port for further investigation by the Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture Development.

Separate AMLEP exercises also have been held recently with Cape Verde and Senegal.

GHANA’S FISHERIES ENFORCEMENT UNIT

Ghana established a Fisheries Enforcement Unit (FEU) in 2013 and authorized it to combat illegal fishing activities, according to the Daily Graphic. The FEU includes personnel from Ghana’s Navy, Air Force, Fisheries Commission, Attorney General’s Department, the Marine Police of the Ghana Police Service and the Bureau of National Investigations.

The FEU monitors and controls all fishing operations within Ghana’s waters. In December 2014, the FEU arrested 26 fishermen on suspicion of fishing with dynamite, an illegal and dangerous practice, the Daily Graphic reported. Still, officials believe there is much work to be done to protect the Gulf’s fish stock for today’s fishermen and for generations to come.

“Of late, seasonal bumper fish catches have become history, and this could be attributed to rampant violation of fisheries laws and regulations, such as pair trawling, light fishing, use of unauthorized nets and net meshes, transshipment and dumping at sea,” said Nayon Bilijo, minister of Fisheries and Aquaculture Development.

This is a big problem for an industry that adds $1 billion to government coffers while providing a livelihood for up to 10 percent of Ghanaians and up to 60 percent of the nation’s animal protein intake, according to The Africa Report. Kyei Kwadwo Yamoah, programs manager for Friends of the Nation, a local nongovernmental organization, summed up the threat.

“There is steady decline in the fishing sector; if the sector declines and collapses, this is a food security issue and national security issue,” he said. “Government must act to protect the sector.”

IUU Fishing Defined

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations endorsed the International Plan of Action to Prevent, Deter and Eliminate Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing in 2001.

Illegal fishing is:

- Conducted by vessels in a nation’s waters without permission or in violation of laws.

- Conducted by vessels of states that are parties to a regional fisheries management organization but that ignore that organization’s measures.

- Conducted in violation of international obligations, such as a regional fisheries management organization.

Unreported fishing is:

- Not reported, or has been misreported, to a relevant national authority or regional fisheries management organization.

Unregulated fishing is:

- Inconsistent with conservation and management of a fisheries management organization by vessels without nationality or by those flying a flag not party to the organization.

- Related to areas or fish stocks for which there are no management measures and where fishing is inconsistent with state responsibilities for conservation under international law.

Bottom Trawling Destroys Livelihoods, Ecosystems

When large fishing boats come into the Gulf of Guinea, they often take away more than just tons of fish. Their tactics can destroy livelihoods, local economies, even the food security of an entire region.

Their indiscriminate methods also can damage or destroy ecosystems. In an article about the plight of fishermen in Senegal, the BBC reported that one Russian ship, the Oleg Naydenov, was caught carrying 1,000 metric tons of fish. Senegal seized the ship and accused it of fishing without a license.

Such ships can scoop up many tons of fish on one expedition. Heavy trawls are the tool of the trade for nearly 90 percent of large industrial fishing vessels, according to Africa in Fact. Trawlers can pull up many tons more fish than quotas allow in a short time, making them common violators of reporting regulations.

Local artisanal fishermen are powerless against such methods. Issa Fall, coordinator of the Fisherman Committee at the bay of Soumbedioune in Dakar, told the BBC that at one time, fishermen in the entire market could count on hauling in 3,500 metric tons of fish per year. By January 2014, that catch had dropped to less than 3,000 metric tons per year.

According to Greenpeace, some pelagic freezer trawlers can freeze and store up to 6,000 metric tons of fish, allowing them to fish for weeks at a time. By contrast, 50 small traditional African fishing boats would have to fish for an entire year to match what one such trawler can catch and process in a single day.

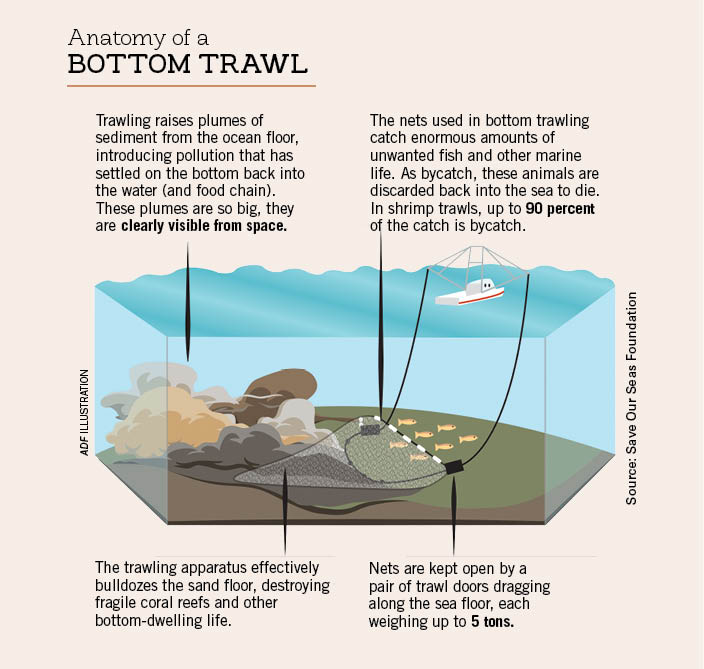

Heavy trawlers are doing more than just depleting regional fish stocks. The gigantic nets, which sometimes are 60 meters across when fully extended, are held on the ocean floor by a pair of trawl doors, each weighing up to 5 tons. As the ship drags the trawl across the ocean floor, it scrapes off everything in its path, such as vegetation and coral, just like a bulldozer.

The drag also stirs up enormous plumes of sediment from the sea bottom. This becomes a pollutant. Many sediment plumes are so large they are visible from outer space.

Finally, nets drawn by trawling ships do not discriminate. Everything in their path is entangled. If a shrimping boat drags a trawl, it may pull up thousands of immature fish, as well as turtles and sharks. This so-called bycatch is unwanted and includes any living thing discarded or killed by fishing gear.