ADF STAFF

It was 2 a.m. on a Saturday when the calm of night in a Burkinabe village was interrupted by the sound of motorcycles, then gunshots.

Terrorists opened fire on residents of the gold-mining village of Solhan on June 5, 2021. They burned homes and markets and executed people until dawn. Local authorities reported at least 160 killed — the deadliest attack since violence spilled into the country in 2015.

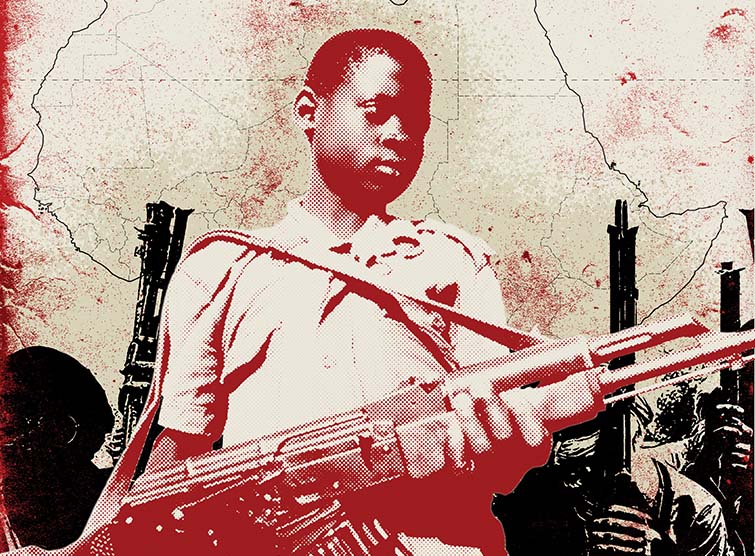

Government spokesman Ousseni Tamboura revealed the most disturbing attack details weeks later: “The attackers were mostly children between the ages of 12 and 14,” he told reporters.

Terror groups such as Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM), Islamic State in the Greater Sahara and al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb have unleashed a rising wave of targeted attacks on civilians in the Sahel.

Recent reports show they are resorting to using children to kill.

“They join because they don’t want to die of hunger,” Yacouba Maiga, head of Catholic Relief Services’ Mopti office, told Al-Jazeera. “They join because if they don’t, another group might kill them.”

“There are young people who know nothing other than this crisis.”

Thousands have been killed and millions forced to flee the regionwide violence. Those numbers, along with mounting losses on the battlefield, have reduced the terror groups’ ability to recruit adults.

Africa has a history of armed groups recruiting and using children in conflict zones.

“Political instability, school closures and COVID-19 have created an environment where children become a useful resource for militants looking to staff their rank and file,” said Christopher M. Faulkner, a postdoctoral fellow in the National Security Affairs Department at the U.S. Naval War College. Faulkner spoke with ADF about his research but did not speak on behalf of his institution or the U.S. government.

“JNIM is using kids in all kinds of ways, including as spies and lookouts. This likely explains why some of these groups pursue children — more resources can improve tactical and operational effectiveness.”

Islamist extremist groups in the Sahel also have exploited food shortages, limited job prospects and an absence of local authorities in the recruitment of children.

Members of these groups preach a radical form of Islam to children in villages and promise food, clothes and money for joining.

Some children were promised about $18 if they kill someone, according to Idrissa Sako, assistant to Burkina Faso’s public prosecutor at the high court in the town of Dori.

For others, weapons and motorcycles offer prestige and status.

“New candidates are often promised a motorcycle and the sum of CFA franc 300,000 to 500,000 [$530 to $885],” a Burkinabe teacher told humanitarian organization Save the Children. “Imagine how a young person who has never held a CFA franc 5,000 or 10,000 note will react when they are offered CFA franc 200,000, 300,000 or 500,000!”

Recruits are trained for anywhere from one week to three months on how to use weapons.

In some instances, girls have been used as suicide bombers because they easily blend in with civilians. But more commonly, girls are at risk of being abducted for labor or forced to marry Islamist fighters.

Some experts and officials believe terror groups have shifted tactics recently to target and destroy schools and kill teachers to undermine the education system and to remove a safe haven for children.

COVID-19 lockdowns and school closures have exacerbated the issue, according to Virginia Gamba, United Nations special representative for Children and Armed Conflict.

“There is a real threat that as communities lack work and are more and more isolated because of the socio-economic impact of COVID-19, we’re going to see an increase in the recruitment of children for a lack of options,” she told Reuters in February 2021. “As children are not in schools, the target of attacking a school for abduction or recruitment of children … is shifting to where the children are.”

Children out of school have mined and trafficked gold in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger.

Jean-Hervé Jezequel, director of the Sahel project for the conflict research nonprofit International Crisis Group, said gold has helped Sahelian extremists procure transportation, weapons and ammunition.

Gold mines neglected by local governments often fall to fighters who hold swaths of largely lawless lands around the countries’ tri-border area, known as Liptako-Gourma.

“Control of the mining sites allows them to extend their influence and gain more funding,” he told Al-Jazeera. “The mines are full of young men who can be easily recruited into jihadi groups.”

Boys and girls still are forced to join armed groups — as fighters, cooks or for sexual exploitation — in at least 14 countries, including Burkina Faso, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mali, Somalia and South Sudan, according to the U.N.

Engaging directly with armed groups sometimes can be productive, as the U.N. showed when its dialogue with Central African Republic militants in 2015 led to the demobilization of more than 350 child combatants.

But it doesn’t happen often because many governments are hesitant to legitimize violent extremist organizations.

One of every three children seriously victimized in the world was in West and Central Africa, according to the 2020 report of the U.N. secretary-general on children and armed conflict.

Children in the Sahel are among the most vulnerable in the world. They are both in supply for and in demand by militant groups.

Maimouna Ba saw nearly 1,200 people who fled the attack on Solhan village seek refuge in the nearby town of Dori, where she directs a civil society organization called Women for the Dignity of the Sahel.

Some survivors said they saw children take part in the attack.

“Those children have no access to a good education, minimum health care, minimum dignity,” Ba told The Associated Press. “They are therefore vulnerable targets and easy to be recruited by extremist groups.”

Reopening schools with improved security measures is one way governments can better protect children. Experts also point to educating children about their vulnerability, about armed groups, and about the existence of disarmament, demobilization and reintegration (DDR) programs.

U.N. Deputy Secretary-General Amina Mohammed said DDR programs are critically important, as are the acceptance and support of communities when children formerly associated with armed groups return.

“Thousands of children recruited and used by armed groups, and other affected children in their communities, do not receive the minimal care or services to reweave the fabric of a torn society,” Mohammed wrote in a 2020 report titled “Improving Support to Child Reintegration.”

“Those that do get help, often do so for just a few months, rather than the essential 3-5 years needed for reintegration.”

The report argues for investment in local education systems and mental health services, noting that significant funding gaps by international groups often disrupt the continuity of DDR programs.

“There is increased attention given by the U.N. to consider deficiencies in reintegration programs,” Faulkner said. “They specifically stress the need for such programs to have a gendered lens so that appropriate resources for girls and boys are available, given that they may have quite distinct experiences in conflict.

“That’s an additional reason for hope.”