Efforts are Underway in Somalia and Elsewhere to Protect Civilians in Peacekeeping Missions

As African Union forces tried to take back Mogadishu, Somalia, from al-Shabaab insurgents, they were faced with a deadly dilemma.

Al-Shabaab had entrenched itself in the capital city’s Bakara Market, on top of a hill in the city’s business district. From the densely populated area, the militants recruited members, extorted money from traders, and dug deep ditches around the market to keep out tanks and military vehicles, Voice of America reported in 2011.

“The problem is that Bakara is a very difficult place,” Rashid Abdi, a Somalia analyst for the Brussels-based International Crisis Group, told VOA. “It is a maze of tightly packed kiosks or stalls. It is teeming with humanity, traders, shoppers. It is a very difficult place to control, and al-Shabaab have used Bakara Market to launch mortar attacks on [government] positions.”

When al-Shabaab fired mortars at African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) forces from inside the market, AMISOM forces would fire back, U.S. and AU officials told The Wall Street Journal in 2010. “We have a problem with return fire,” an AU official said. “It’s become a real, serious issue.”

How to engage in the increasingly complex task of a peacekeeping mission while protecting civilians, or at least not harming them, continues to vex Soldiers, politicians and humanitarians. U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon summed up the issues during an address to the Security Council in June 2014:

“United Nations peacekeeping operations are increasingly mandated to operate where there is no peace to keep,” he said. “We see significant levels of violence in Darfur, South Sudan, Mali, the Central African Republic and the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, where more than two-thirds of all our military, police and civilian personnel are operating.”

He said that “peacekeeping operations are increasingly operating in more complex environments that feature asymmetric and unconventional threats.”

Prioritizing Protection of Civilians

The U.N. in 1999 added a protection of civilians (POC) from physical violence provision to the U.N. Assistance Mission in Sierra Leone (UNAMSIL), the first time a peacekeeping mission had been given such a mandate.

Security Council Resolution 1270 states that “UNAMSIL may take the necessary action to ensure the security and freedom of movement of its personnel and, within its capabilities and areas of deployment, to afford protection to civilians under imminent threat of physical violence.”

Ten years later, the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs and Department of Peacekeeping Operations looked more closely at the U.N. POC policies. They found that “the U.N. Secretariat, troop- and police-contributing countries, host states, humanitarian actors, human rights professionals, and the missions themselves continue to struggle over what it means for a peacekeeping operation to protect civilians, in definition and in practice.”

The report found the following gaps in POC policies at the field level:

• Lack of missionwide strategy: Although various missions develop their own tools and strategies, they tend to do be “conceived and elaborated on an ad hoc basis.”

• Leadership matters: Understanding and prioritization of POC is inconsistent.

• Structures and resources: Mandates and missions cannot succeed if the operation is not set up or resourced to meet its objectives.

• Information collection and analysis is critical: Most missions do not have the ability to collect and analyze information to address threats or predict potential escalations in violence.

Information is key, and finding a way to gather, analyze and react to data about civilian harm is what one group has worked on in Somalia in conjunction with the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM). The effort is called the Civilian Casualty Tracking Analysis and Response Cell.

Tracking Civilian Harm in Somalia

Marla Keenan, managing director of the Center for Civilians in Conflict, said her group began working in Africa in 2010. At the time, AMISOM was trying to take back Mogadishu and the rest of the country from al-Shabaab extremists. Fighting in populated areas often involved civilian harm, ranging from injury and death to displacement and property damage.

Keenan said her colleagues, together with a personal injury attorney, began by talking to civilians in the Dadaab refugee camps in Kenya about how the operation had affected them. They also talked to humanitarian workers and gathered data for a report, which was circulated to AU, AMISOM and nongovernmental organization contacts. Soon after, a British general working with AMISOM to craft an indirect fire policy contacted the center.

Most civilians harmed by AMISOM forces were victims of indirect fire, such as those resulting from battles centering on Mogadishu’s Bakara Market.

A lack of tracking makes it impossible to quantify the number of civilians killed or injured as a result of AMISOM or al-Shabaab actions. However, Walter Lotze and Yvonne Kasumba wrote in a 2012 article titled “AMISOM and the Protection of Civilians in Somalia” that a report showed as many as 1,400 civilians died in the first half of 2011 alone. Another report indicated as many as 4,000 civilians had been injured during roughly the same time frame, Lotze and Kasumba wrote.

Both sides relied on artillery fire, Lotze and Kasumba wrote, placing civilians’ lives and property at risk. “Al-Shabaab exploited this tactic, firing mortars at AMISOM positions from densely populated areas,” they wrote. “They then used civilians as human shields when AMISOM used retaliatory fire.”

AMISOM is unique, Keenan told ADF, because it has an offensive mandate to go after al-Shabaab. In many ways, it’s more like a counterinsurgency operation. That context makes the Civilian Casualty Tracking Analysis and Response Cell all the more important.

AMISOM is unique, Keenan told ADF, because it has an offensive mandate to go after al-Shabaab. In many ways, it’s more like a counterinsurgency operation. That context makes the Civilian Casualty Tracking Analysis and Response Cell all the more important.

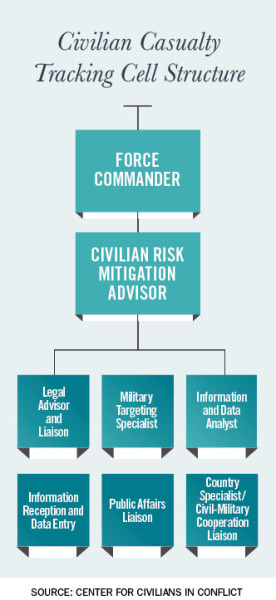

Although it sounds technical, the tracking cell is primarily a people-based system, Keenan said. Those comprising the cell are expected to understand the impact of operations and pass along information from various areas. That information then can be analyzed to allow for adjustments in the field to avoid civilian harm or address harm already occurring. Information collected can be directed to the force commander.

The tracking cell was expected to become operational before the end of 2014. Keenan was optimistic about its ability to reduce harm to civilians because of success associated with the indirect fire policy, which went into effect in 2011. The policy establishes no-fire zones in heavily populated areas. “When tactical directives were issued on the things that were causing civilian harm, civilian harm went down,” she said. “So these policies and these practices are actually incredibly important, and they’ve been shown to decrease civilian harm.”

Work in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

In the DRC, the center persuaded the U.N. to include language on mitigating risk to civilians in the Force Intervention Brigade mandate. This is the first time a peacekeeping mandate recognizes civilian risk from its own actions.

The mandate says the Intervention Brigade will “ensure within its area of operations effective protection of civilians under threat of physical violence, including through active patrolling, paying particular attention to civilians gathered in displaced or refugee camps, humanitarian personnel and human rights defenders in the context of emerging from any of the parties engaged in the conflict, and mitigate the risk to civilians before, during and after any military operation.”

The eastern DRC has been rife with conflict for years from a variety of factions, including M23 rebels, the Lord’s Resistance Army and the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda.

The Security Council created the Intervention Brigade in March 2013 with three infantry battalions, one artillery unit, one special force division and a reconnaissance company with headquarters in Goma to operate under U.N. command. The brigade carries out offensive operations “in a robust, highly mobile and versatile manner” to disrupt violent factions, the U.N. said. The U.N. Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the brigade’s mandate were extended through March 31, 2015.

Sometimes, however, civilians aren’t harmed by guns, artillery and the damage they cause. Large-scale peacekeeping missions such as the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) can bring thousands of Soldiers and hundreds of staff members into a city, altering the cultural and economic equilibrium.

The Approach in Mali

A country such as Mali presents some of these other challenges to civilians. The mission is authorized for 12,640 uniformed personnel and had deployed about 9,300 as of August 31, 2014. A mission of that size can shift the economic dynamics of a city or region.

Food prices can go up, water can become scarce, housing prices increase — even traffic volume changes. These factors can combine with potential property and physical harm to affect civilians.

The Center for Civilians in Conflict helped persuade the U.N., through the Department of Peacekeeping Operations, to establish a “civilian risk mitigation advisor” position with MINUSMA. Keenan described it as a one-person casualty tracking cell. The person would work with the Joint Mission Analysis Center, the Joint Operations Center, and the human rights and protection divisions to gather information about civilian harm.

Because MINUSMA doesn’t involve as many offensive operations, the position could focus on a wider range of harm. The position is the first of its kind for a peacekeeping mission. However, as of fall 2014, it still had not been filled.

More Than Just Prevention

AMISOM has taken steps to reduce civilian harm in Somalia, and that commitment has been reinforced at the highest levels of the mission and the AU. In 2012, Ambassador Boubacar Gaoussou Diarra, a former representative of the African Union Commission for Somalia, said authorities would investigate and rectify any credible reports of indiscriminate harm to civilians.

“AMISOM takes its responsibility for the safety of the people of Somalia very seriously and fully understands its obligations to conduct operations without causing undue risk to the local population,” Diarra said. “We urge all other military forces active in southern Somalia to exercise due restraint in areas with a substantial civilian population.”

Protecting civilians goes beyond avoiding physical harm or loss of property. Effective measures also should have a way to make amends, Keenan said. Amends can come in the form of an “apology, dignifying gestures, monetary payments, in-kind sort of offerings to the families that have been harmed as a way of saying, ‘This wasn’t our intention, and we recognize that we’ve caused harm,’ ” she said.

Those types of gestures are in keeping with what Somali tribes and groups would do if someone harmed another. Making amends also is an effective way to maintain legitimacy of a mission in the eyes of civilians.

“Harming civilians will harm the mission,” Keenan said. “How much you can win back of that negative public opinion, it’s difficult to know.” If Soldiers will try to avoid harm and address the harm that is caused, it’s likely that would help peacekeepers achieve their “ultimate mission.”