ADF STAFF

The sleepy forests and villages of the Foni Kansala district in The Gambia erupted January 24 as Soldiers chased a truck filled with timber.

What followed was the latest spasm of violence in the Casamance region of Senegal, the location of one of Africa’s longest-running conflicts. But this time there is hope it could lead to peace.

“In their pursuit, the men of the fifth military zone crossed, perhaps without knowing it, the border with Senegal — ‘a line in the sand,’ describes a regular of the place,” Le Monde newspaper reported. “They would then have entered one of the cantonment [military camp] areas of the MFDC [Movement of Democratic Forces of Casamance], led in northern Casamance by Salif Sadio, a historic rebel leader.

“The soldiers then came under fire from small arms and rocket launchers, returned fire and then retreated to The Gambia.”

The Soldiers were monitoring timber trafficking as part of ECOMIG, a peacekeeping mission in The Gambia from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) regional bloc.

The battle claimed the lives of four Senegalese Soldiers and one member of the MFDC. Seven Senegalese Soldiers were taken prisoner.

Residents worried that the skirmish could reignite long-simmering tensions. But when the Soldiers were released unharmed three weeks later, some hailed it as a sign that peace might finally be on the horizon.

Robert Sagna, the former mayor of the Casamance regional capital, Ziguinchor, is among the hopeful.

“There is a real lull,” he told Le Monde. “Not yet peace, but we must at all costs avoid a resurgence of war.”

Since 1982, the MFDC has been fighting for control of the southwestern region of Senegal between The Gambia and Guinea-Bissau. The population of Casamance is culturally and ethnically distinct from the rest of Senegal.

Casamance residents have long complained of being left behind in terms of economic investment and social services, leading some to support independence. However, the rebel group’s brutal tactics, including kidnappings and executions, and its connection to the illicit trafficking have caused many civilians to stop supporting it.

Fighting displaced tens of thousands over 40 years, while thousands have died, including many civilians reportedly because of land mines planted by rebels.

The conflict peaked from 1992 to 2001 with more than 1,000 battle-related deaths. The region has since experienced sporadic flare-ups, cease-fire agreements and lulls, while the MFDC has broken into factions.

In May 2014, Sadio sued for peace with Senegalese government representatives and declared a unilateral cease-fire after the Community of Sant’Egidio, a lay Catholic association, arranged secret talks at the Vatican.

With most factions adhering to the cease-fire, the conflict has been described in recent years as a low-intensity insurgency.

After a Senegalese offensive swept through several deep-forest rebel bases in Casamance in 2021, the government set its sights on eroding the MFDC by tackling its revenue streams — illegal logging and cannabis trade.

From September 2021 through January 2022, Senegalese forces deployed in the border area increased operations to destroy marijuana crops cultivated by the MFDC. During that time, troops intercepted 77 trucks illegally transporting highly valuable rosewood, teak and other hardwoods from the forests of Casamance to be exported from The Gambia, according to the Army.

A battle was inevitable, but peace is still on the table.

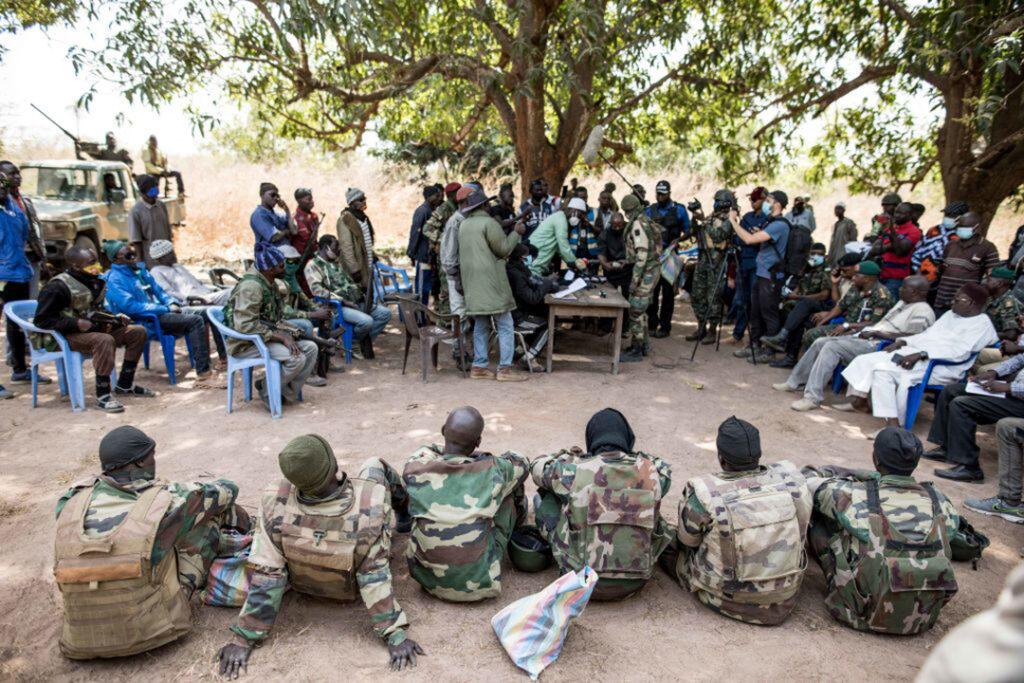

When the MFDC released the seven Soldiers to ECOWAS custody February 14, Sadio said he did so “unconditionally” to restore a “climate of trust” with the Senegal government.

“This is clearly the bloodiest clash since the unilateral truce decreed in 2012 by the MFDC. Everyone was surprised,” a Sant’Egidio leader told Le Monde. “In the past, the Senegalese government and army have often responded with force to this kind of event. It seems that everyone today wants to reduce the pressure.”