ADF STAFF

Zambia is buckling under the weight of foreign debt, and its economic troubles are causing ripples around the world.

The country formally defaulted on a $42.5 million Eurobond payment in mid-November. The default came at the end of the monthlong grace period Zambia received to make good on its October bond payment. During that month, Zambia failed to reach an agreement with its creditors and the International Monetary Fund, which wanted more transparency regarding its debts to China before providing any relief.

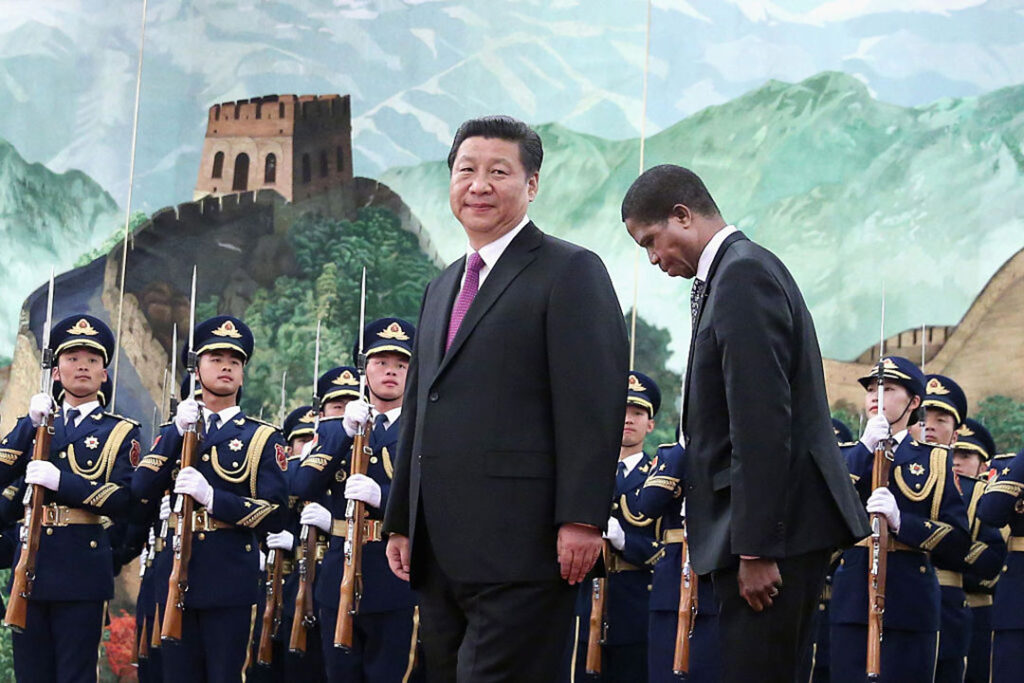

As a result, Zambia became the first African nation to default, underlining the severe economic toll COVID-19 has had and highlighting the need for debt relief from Zambia’s single-largest creditor, China.

During recent relief negotiations, Zambia hit a roadblock: Some Chinese loans come with confidentiality agreements that keep nations from revealing information. Chinese lenders said Zambia could release information to bondholders but only if the bondholders too signed confidentiality agreements.

“The position of the Chinese banks is: ‘You’re not going to give anybody any information without the confidentiality agreements in place,’” Zambian Finance Minister Bwalya Ng’andu told the nation on state television after the default.

The default affected $3 billion in bonds, about a quarter of Zambia’s total foreign debt. It also raised questions about the future of $6 billion held by Chinese entities, including the Export/Import Bank, Development Bank and the Bank of China.

Zambia already was $200 million behind on payments to Chinese lenders before its Eurobond default. It has negotiated a preliminary relief agreement with the Development Bank of China but has reached no deals with the other two banks.

Zambia could be the first trickle in a cascade of future defaults among African nations that increasingly find themselves caught between caring for their citizens during the global pandemic and repaying loans from Chinese banks.

Lusaka-based financial analyst Trevor Hambayi told ADF that other nations are likely to use the threat of a Zambia-like default to secure favorable terms from their creditors through the G20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) or directly from Chinese banks.

“They will be looking to leverage Zambia’s position to ensure they can lock in agreements that provide them debt repayment relief either as part of the G20 DSSI strategy,” Hambayi said, “or indeed the Chinese relief program without necessarily defaulting on the repayments.”

Neighboring Mozambique recently joined the list of countries warning of a potential default. Analysts worry that Kenya, which has large Chinese debts and original declined relief from the G20 only to reverse that position in mid-November, could be headed the same way.

Nations considering a default on Chinese debt need only look across the Indian Ocean for a glimpse of their possible future: Sri Lanka was forced to lease its Hambantota Port — 85% financed by China’s Export/Import Bank — to the state-owned China Merchants Port Holdings company for 99 years after failing to meet its debt obligation.

Zambia’s default could cost it control of Zesco, its heavily indebted national power company.

For now, Zambians face more pressing concerns. The default has reduced Zambia’s bond rating to junk status, wrecking its ability to borrow to support its 2021 budget. The national currency, the kwacha, lost a third of its value versus the U.S. dollar after the default, increasing prices on imports and making it harder to pay off Zambia’s remaining debts.

“This will reduce Zambia’s confidence in the eyes of lenders; as such, it will be difficult for the country to borrow in the future or attract foreign investment,” Emmanuel Mbambiko, vice president of the Chamber of Commerce in the copper belt community of Kitwe, told the Zambia News and Information Service.

The default also is likely to reduce the flow of foreign money into Zambia in the form of direct investments and could induce current investors to pull out rather than risk their money, Hambayi said.

“It will also impact on the country’s private sector international transactions capacity,” Hambayi said. “Locals may not have their instruments accepted on the international market.”

Zambia’s dark economic cloud has a silver lining, however: Copper production is up, and prices, which provide 70% of the country’s export income, are rising for the first time in six years. Forecasts call for strong demand in 2021.