Institutions Look for New Methods to Produce Better Peacekeepers

Peacekeeping is sometimes called a paradox because it requires the ability to use force and the restraint not to use it. Former United Nations Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjold summed up the challenge when he said: “Peacekeeping is not a job for Soldiers, but only Soldiers can do it.”

Modern peacekeepers face daunting tasks. They must deploy to a foreign country where they may not speak the language. They must quickly assess the situation on the ground, where a war has just been fought or is ongoing. They must encourage dialogue between warring parties, protect civilians, follow international law, operate within the mission mandate and so on.

The complexity of modern peacekeeping makes training vitally important. But what is the best way to maximize this training amid funding and time constraints?

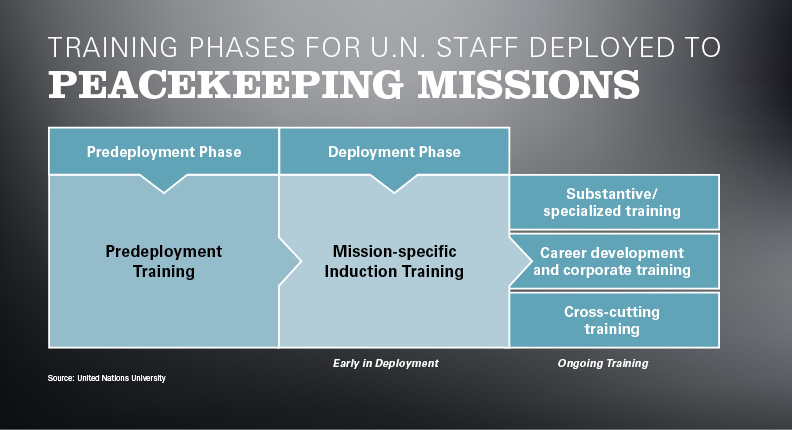

U.N. staff deployed to peacekeeping missions undergo three phases of training. Predeployment training is the crash course on everything a peacekeeper must know before serving in a mission. It typically lasts two weeks. Mission-specific induction training occurs in country and refreshes some of the things taught in the predeployment phase while offering new information on issues unique to the mission. It lasts one to six days. Ongoing training occurs during deployment and could be specialized training, career development courses or technical skills.

Critics point out that the volume of material peacekeepers are expected to master before deployment is daunting. For example, a two-week predeployment session for police officers in the United Nations-African Union Hybrid Operation in Darfur covered 21 subjects, including map reading, radio use, the mission mandate and land mine awareness.

“How can anyone be expected to learn all of these subjects — and then apply them in a conflict setting — within two weeks?” wrote researcher Anne Flaspoler. “Ambitious is one way to describe it!”

Trainers and troop-contributing countries are looking for a better way.

Peacekeeping Training Centers

Training options have multiplied in the past 25 years as peacekeeping has expanded and more countries have contributed troops. There are now training institutions and prepackaged courses that can be adapted to match the needs of deploying forces. In 1995, the International Association of Peacekeeping Training Centres was founded to help these institutions share information. It has 265 members, including government agencies, universities, think tanks and regional organizations.

African nations are playing a leading role in staffing peacekeeping missions. At any given moment there are 60,000 troops from 39 African nations serving in peace support operations across the globe. Countries such as Ghana, Rwanda, Senegal and South Africa have deep reserves of peacekeeping knowledge gained from operations that date back decades.

Homegrown training assets also are on the rise on the continent. In 2004, Ghana opened the Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre (KAIPTC). It is a training hub for personnel from across West Africa and offers predeployment and other training for military, police and civilians serving in peace support operations. The center has provided more than 400 courses to more than 11,000 people since it opened. In addition to the KAIPTC, there are seven other peacekeeping training institutions in Africa.

Foreign partners also contribute. Since 1997, the Africa Contingency Operations Training and Assistance (ACOTA) program funded by the U.S. Department of State has trained hundreds of thousands of peacekeepers from African countries.

As nations expand their peacekeeping training capacity, they will look at ways to make it more effective.

Focus on impact

Historically, training has been measured in terms of time spent in classrooms or the number of certifications handed out. These are simple benchmarks, but they don’t measure effectiveness of the training.

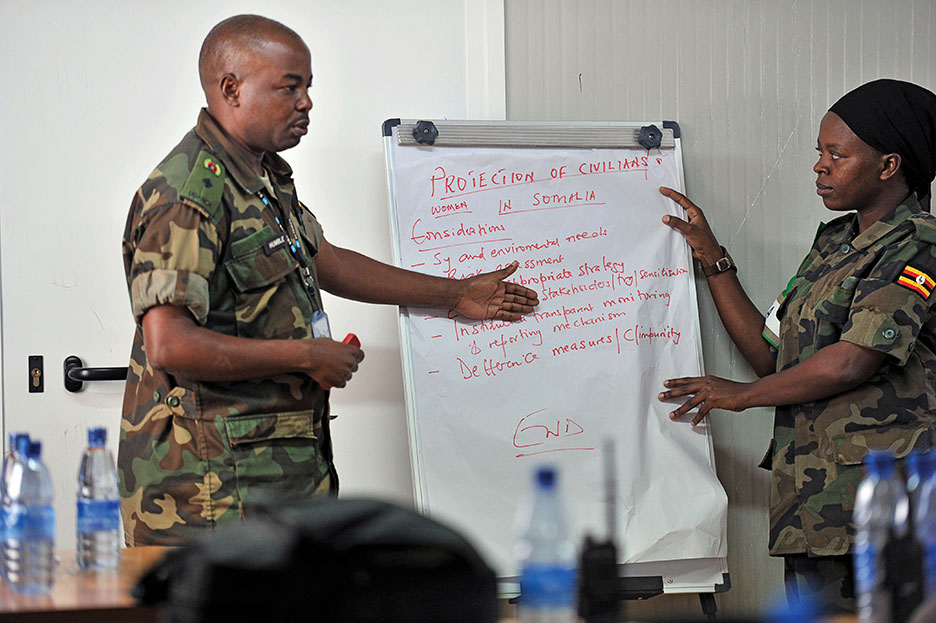

Newer evaluations measure the acquisition and application of skills by trained Soldiers. For instance, if a peacekeeper is taught that there are certain instances where he must intervene to protect civilians, it is not enough to simply show that fact on a PowerPoint slide. The only way to know whether the peacekeeper has internalized the information is to see how he or she reacts in a complex and nuanced scenario.

This is the difference between transferring knowledge and changing behavior, said Flaspoler in her book, African Peacekeeping Training Centres: Socialisation as a Tool for Peace?

“Knowledge and commitment are not enough, given the complexities faced by peacekeepers,” Flaspoler wrote. “Peacekeepers cannot be prepared for the ethical complexity of the realities encountered in the mission by [only] teaching them codes of conduct and laws.”

Suzanne Monaghan, formerly of the Pearson Peacekeeping Centre in Canada, said many of the old ways of teaching simply don’t work for peacekeepers. She found that adults retain 10 percent of what they read, 20 percent of what they hear and 90 percent of what they do. “We can’t lecture for fifteen days and think learners will leave the classroom knowing exactly what to do,” Monaghan wrote. “We need to actively engage participants in role playing, small group discussions and problem solving.”

The U.N.’s Integrated Training Service is working to measure impact with better evaluations during deployment. These evaluations take a 360-degree approach by interviewing not only the peacekeepers, but also commanders, peers and civilians.

In 2018, Jean-Pierre Lacroix, undersecretary-general for Peacekeeping Operations, announced more rigorous performance assessments of troops, including an emphasis on command and control, protection of civilians, conduct, and discipline. The U.N. also seeks a more stringent evaluation of predeployment training by testing units for readiness before they reach the field.

“We are devoting considerable attention to better assessing performance,” Lacroix said. “We are putting in place the policies and evaluation systems that will enable all of us, collectively, to better tailor our efforts to strengthen peacekeeping.”

Keep it Fresh

All training is perishable. Soldiers trained on military tasks show diminished skills after 60 days and, by 180 days on average, they have lost 60 percent of what they learned, according to the U.S. Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences. “A trained peacekeeper in the past is not a trained peacekeeper in the present,” wrote Daniel Hampton of the Africa Center for Strategic Studies.

This is why peacekeeping training must be regularly reinforced. The U.N. includes training for forces throughout their deployment and recently created mobile training teams (MTTs) to focus on mission-specific training in country. For instance, an MTT specializing in countering improvised explosive devices might deploy to Mali to help peacekeepers dealing with asymmetric threats.

Still, the problem of skill loss runs deep. Troop-contributing countries can only maintain training capacity if they keep units together over extended periods and develop their own pool of trainers. This is difficult because peacekeeping units tend to rotate out every six months, and much of the predeployment training is done by international trainers.

Organizations such as the U.N. Institute of Training and Research have invested in train-the-trainers programs to help build domestic capacity for peacekeeping training among troop-contributing countries.

“Ideally, a professional cadre of peacekeeping trainers would exist within a defense force’s [professional military education] system at an institutionalized peacekeeping training school or center,” Hampton wrote.

“Ideally, a professional cadre of peacekeeping trainers would exist within a defense force’s [professional military education] system at an institutionalized peacekeeping training school or center,” Hampton wrote.

To promote continuity, the U.N. has created the Peacekeeping Capability Readiness System (PCRS). Through the PCRS, countries pledge to have units ready for deployment within 60 days of a request by the secretary-general. These units train together, have their own equipment and are evaluated regularly to ensure high performance.

This avoids constant retraining, lack of equipment and lack of cohesion. One U.N. official said that peacekeeping used to be akin to building the fire station after the house was on fire. They hope the PCRS will change that dynamic by improving readiness.

“Now we have a firehouse, we have a fire engine. We have capabilities registered to us that are deployable,” the U.N. official said.

Win Hearts and Minds

Peacekeeping is most effective when the mission wins the trust and the support of the local population. Doing so requires specialized training.

One of the main barriers to winning local support is inadequate cultural training. A 2012-2013 report by the U.N. on peacekeeping training found that briefings given to peacekeepers on cultural awareness during induction were not enough, and more in-depth training was needed.

UNAMID

Brig. Gen. Emmanuel Kotia of Ghana, who served in the U.N. mission in Lebanon, recalled that during that mission some peacekeepers drank in public, which angered Lebanese civilians. Additionally, the U.N.’s failure to consult with local leaders about road-building projects led to delays and obstruction. These were easily avoidable cultural missteps.

Kotia said peacekeepers, especially officers, need to have the tools to win over the public. “Have tea with them,” Kotia said. “Invite them to social events and sports competitions. These are your partners.”

To replicate these situations, some peacekeeping training institutions have created mock villages with actors portraying locals in tricky scenarios.

Mediation and conflict management also helps. Good peacekeepers can serve as trusted mediators who can broker deals between warring parties. The U.S. Institute of Peace (USIP) through ACOTA offers a class in conflict management training for peacekeepers. The institute has trained 5,700 peacekeepers using experiential exercises, scenario-based problem solving, and role playing.

In a 2017 study of mediation training, USIP found that peacekeepers called it one of the most useful skills they had while serving in a mission. Nearly all interviewed wanted more training on cultural awareness and on how to use dialogue to deescalate conflict.

“If you go to a mission, you are not going there to use force,” a Togolese Soldier told USIP. “If there is any problem or conflict, the first thing that you have to do is use negotiation. … You have to be a good Soldier by talking to the people, by trying to know the problem.”