When it comes to unmanned military vehicles, most people tend to think of the sky, where attack and surveillance drones are a fixture in armed conflict. But experts say the next wave of unmanned craft will set sail on the water.

Navies are investing in uncrewed surface vessels (USVs) and uncrewed underwater vehicles (UUVs). If trends continue, more than 40 countries will operate USVs by 2034, and the global USV market will grow from $1.1 billion to $2.5 billion, according to the research company GlobalData.

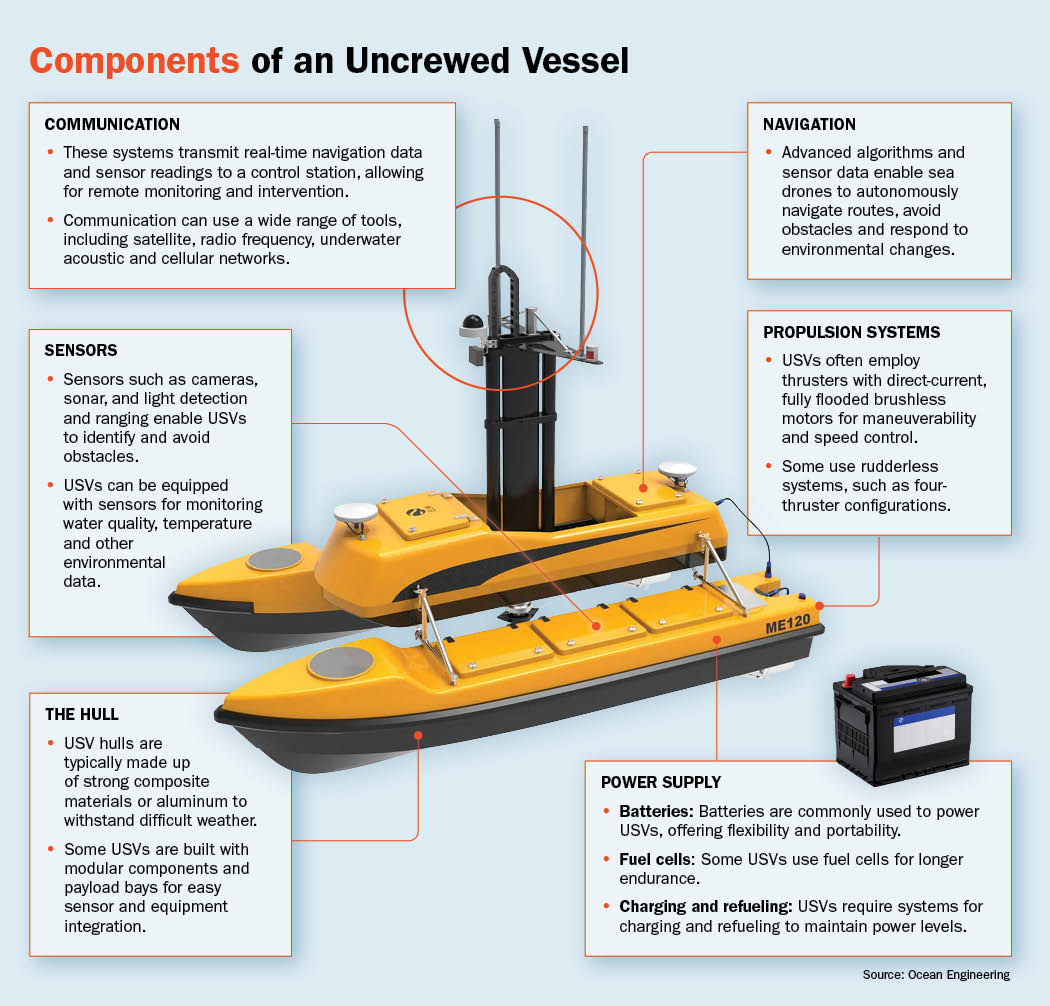

These sea drones can be controlled by operators on shore or sail semiautonomously, following a programmed course and using a suite of sensors to navigate. Advocates say they can save navies money, time and lives by taking Sailors out of harm’s way during long, dangerous missions.

The advantages are clear, and private industry has led the way. USVs are already used widely to inspect and safeguard oil platforms, undersea cables and other infrastructure. In Africa, where navies often have small, outdated fleets to patrol sprawling territorial waters, analysts believe it’s time to invest in the technology.

“These advances have turned USVs into a genuine force multiplier,” Matthew Ratsey of the company Zero USV told South Africa’s Engineering News. “They extend the reach of maritime forces, enabling missions over larger areas without ports, offshore energy platforms and subsea cables, providing round-the-clock surveillance and real-time threat detection.”

A Long History

The use of USVs dates to World War I when the United Kingdom’s Royal Navy deployed “distance control boats,” which were fitted with torpedoes and controlled by nearby aircraft. In subsequent decades, surface drones’ use expanded to include tasks such as minesweeping, surveillance, target practice and as kamikaze vessels loaded with explosives. At the turn of the 21st century, however, surface drones remained a niche tool used mainly by scientists for mapping seafloors and monitoring ocean conditions.

The Sea Hunter, a 40-meter trimaran, is one of the first fleet class USVs commissioned by a navy. The U.S. Navy acquired it in 2016 and is testing it for a variety of missions.

Navies today are in a race to acquire USVs and UUVs, but, according to Jonathan Bentham of the International Institute for Security Studies (IISS), they still are largely at the stage of putting their “toes in the water” when it comes to using them. About 75% of uncrewed platforms evaluated by IISS were determined to be experimental.

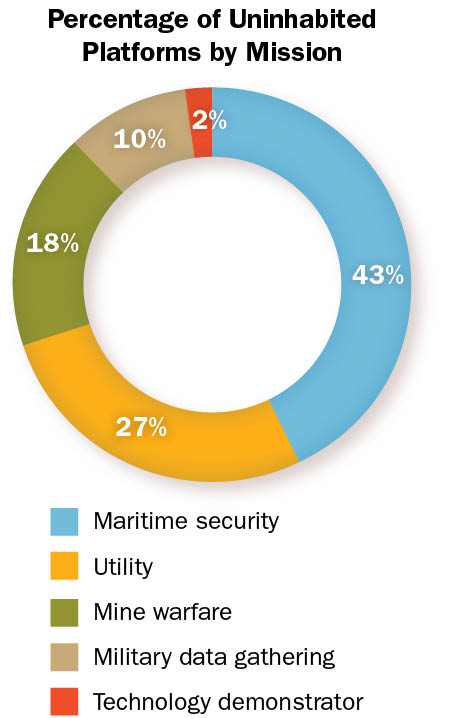

The IISS says the platforms fall into four general categories:

- Maritime security: designed and used for patrol or interception missions.

- Military data gathering: used to collect information on the maritime environment, including hydrographic or oceanographic surveys.

- Mine warfare: vehicles used to identify or dispose of sea mines.

- Technology demonstrator: vehicles that have a clear military capability and operational role, but are built to demonstrate and advance a capability rather than perform front-line duties.

Bentham wrote that the technology is advancing rapidly.

“Navies around the globe … are embracing the technology across a diverse mission set. While [USVs] appear to be completely different entities from their traditional ship counterparts, they are increasingly being used alongside each other,” Bentham wrote for the IISS. “Many [USV] applications are still experimental, but the technology, in some form or another, is here to stay.”

Denys Reva, a maritime security expert at the Institute for Security Studies (ISS), cautioned that USVs are not a cure-all and might not be the right fit for countries with limited capacity to patrol their exclusive economic zones and respond to threats.

“It’s a useful tool at a fraction of the cost of a conventional tool,” Reva told ADF. “But much will depend on which country is using it. Because some countries, their problems are not the kind of problems that can be resolved with additional ability to detect threats. The challenge is responding to them.”

Ukraine Shows a Way

Despite this long history, surface drones have been a rare sight in maritime warfare. That changed with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. The Black Sea became a hotly contested battle space, and Ukraine, which does not have warships, fended off Russia’s Navy using sea drones.

Ukraine deploys a domestically produced vessel known as the Magura V5 for surveillance, reconnaissance, mine warfare and kamikaze attacks.

Viktor Lystopadov, regional director of Ukraine’s SpetsTechnoExport, told defenceWeb that the USVs have changed the rules of modern conflict. He said his country has been able to destroy more than 20 Russian vessels valued at $2 billion using sea drones that cost a small fraction of that. In 2024, a Ukrainian USV shot down a Russian Mi-8 helicopter, he said, which is believed to be the first instance of a sea drone downing a piloted aircraft.

Retired U.S. Gen. David Petraeus called the Ukrainian use of maritime drones and other technology “sheer genius.” “For Ukraine to sink over a third of the Russian Black Sea Fleet and force its withdrawal from Sevastopol and the western Black Sea without any substantial naval assets is an extraordinary tribute to both the Ukrainian tech sector and those in uniform operating these systems,” he said in an interview with the Kyiv Post.

Navies across the world are monitoring this as a successful offensive strategy that reinforces the need for new defensive strategies.

“Navies and planners will no doubt be looking at the war closely,” wrote analyst H I Sutton for the Royal United Services Institute. “It redraws the threat picture for larger navies that are looking to prepare for future operations. And for countries facing similar threats, uncrewed platforms offer significant advantages. The age of naval drone warfare has arrived.”

Drones Give Insurgents an Advantage

At the same time a national navy is successfully using drones, countries are being reminded of the dangers they pose in the hands of insurgents.

In the Red Sea, Iran-backed Houthi rebels have used explosive-laden maritime drones to attack ships and disrupt commerce. An attack on February 18, 2024, was notable because it was the first Houthi attack that included an underwater drone.

Observers say traditional sonar, mine detection capabilities and other tools used in anti-submarine warfare might be needed to protect against this threat. Scott Savitz, an analyst for the Rand Corp., said the Red Sea attacks are a preview of a sort of cat-and-mouse game. As navies get better at detecting and destroying sea drones, adversaries improve their ability to conceal them.

“The age of explosive USVs is just beginning. Navies that can effectively use these systems could have a great advantage over their adversaries,” Savitz wrote. “A classic cycle of measures and counter-countermeasures will likely begin.”

He predicted that naval fleets would deploy sensor-studded aerial drones to detect and destroy USVs. He also said drones could use propeller-entangling fibers to halt the advance of USVs. However, those advantages likely will be short-lived as adversaries adapt.

“Regardless of the specific measures used by both sides, explosive USVs could become a centerpiece of naval warfare in the coming decades, one that navies may ignore at their peril,” Savitz wrote.

A Variety of Missions

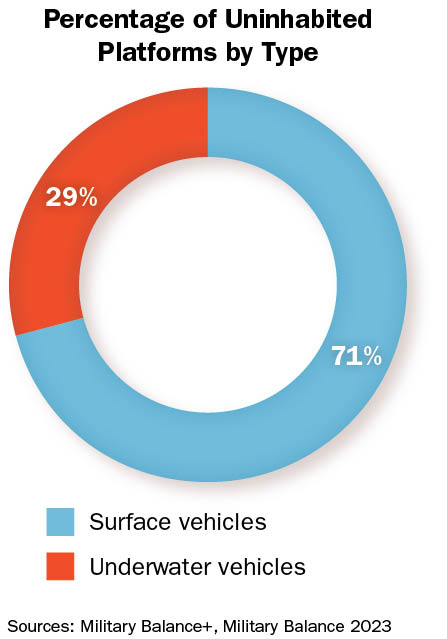

A review of data by Military Balance+ of uninhabited maritime platforms found that the largest number was being used for maritime security, a category that includes patrolling and interception missions. The survey also found that surface vessels outnumber underwater vessels by a ratio of more than 2-to-1.

With 30,500 kilometers of coastline, sprawling ocean domains, and innumerable deltas, rivers and lakes, African navies have enormous responsibilities. To expand their reach, some countries are investing in aerial, surface and underwater drones. Here are a few examples:

Egypt announced its first domestically produced USV designed for patrol and coastal security in 2024. The B5 Hydra created by Amstone is 2.1 meters long, has a payload of 600 kilograms and can reach speeds of 85 knots. The USV is armed with a remote-controlled 12.7 mm machine gun and is equipped with a small aerial drone that can be launched for reconnaissance operations. The ship was built in collaboration with Cypriot company Swarmly and Italian company Leonardo.

In South Africa, shipbuilder Legacy Marine is building a 9.5-meter vessel that uses artificial intelligence and robotics to navigate. It is believed to be the first sea drone fully built and tested in South Africa.

The Nigerian Navy acquired two SwiftSea Stalker USVs from U.S. manufacturer Swiftship. The vessels, with a range of 400 nautical miles and a speed of 45 knots, are expected to be used in the Niger Delta, Lake Chad and other difficult-to-patrol waterways.

Observers believe this is just the beginning as militaries look for ways to improve their presence on the water at lower costs. Security forces also need to anticipate the next move from nonstate actors.

“Now is the time for African states to start thinking about what will happen if these technologies are being deployed. Because technology only becomes cheaper and that changes the circumstances,” Reva, of the ISS, told ADF. “These tools exist and, even if it’s not practical for groups to deploy them right now, you don’t know what will happen tomorrow.”