THOMSON REUTERS FOUNDATION

Photo by THOMSON REUTERS FOUNDATION

Halima Sheikh Ali is the proud owner of one of the few ATMs in Wajir town in northeast Kenya. But rather than doling out shilling notes, it dispenses something tastier: fresh camel milk.

“For 100 Kenyan shillings [$1], you get a liter of the freshest milk in Wajir County,” she said, opening a vending machine advertising “fresh, hygienic and affordable camel milk” to check the liquid’s temperature.

East Africa, one of the world’s biggest camel producers, also produces much of the world’s camel milk, almost all of it consumed domestically.

“Camel milk is everything,” said Noor Abdullahi, a project officer for U.S.-based aid agency Mercy Corps. “It is good for diabetes, blood pressure and indigestion.”

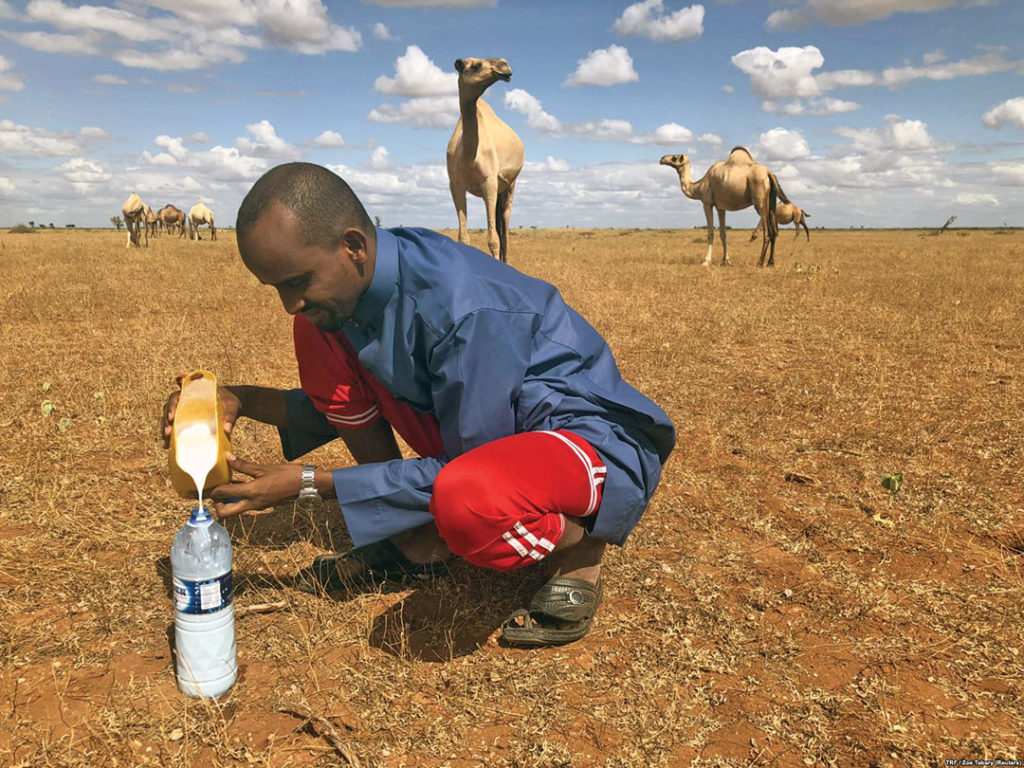

But temperatures averaging 40 degrees Celsius in the dry season, combined with the risk of dirty collection containers, mean the liquid can go sour in a matter of hours. To remedy this, an initiative is equipping about 50 women in Hadado, a village 80 kilometers from Wajir, with refrigerators to cool the milk that remote camel herders send them via small taxis, plus a van to transport it daily to Wajir. There, a dozen female milk traders, including Sheikh Ali, sell it through four ATM-like vending machines after receiving training on business skills such as accounting.

“The [milk] supply and demand are there,” Abdullahi said. “We just have to make it easier for the milk to get from one point to another.”

Asha Abdi, a milk trader in Hadado who operates one of the refrigerators with 11 other women, said she used to have to boil camel’s milk — using costly firewood — to keep it from turning sour. Now, Abdi and the other women in her group send about 500 liters of fresh milk to Wajir every day — a trip that takes just more than an hour by van. They reinvest the profits in other ventures.