ADF STAFF

Although Somalia is known as home to the extremist group al-Shabaab, another rival terrorist organization is making a name for itself in the Horn of Africa nation: the Islamic State Somalia, or ISSOM.

The group is much smaller than al-Qaida affiliate al-Shabaab, but from its base in Puntland’s Bari region, it has come to be known as the East African headquarters of the Islamic State group and a major player in IS financing across the globe.

“In Puntland, it generates funds by extorting businesses in the seaport city of Bosasso, as well as by helping export small quantities of gold mined in Bari,” according to a September 12 report from the International Crisis Group. ISSOM is thought to have collected about $6 million since 2022, and it handles fund transfers for a number of IS offices and cells.

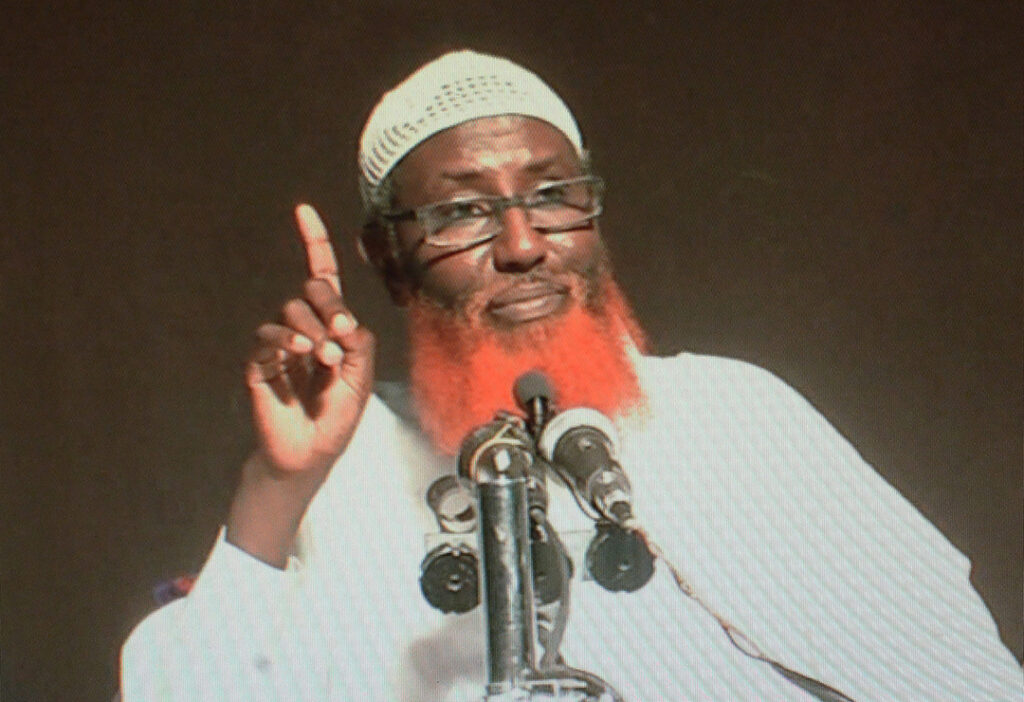

Another issue raising concern is news that ISSOM’s leader, Abdulqadir Mumin, might now be the global head of IS. An airstrike targeted him in May, but he is thought to have survived. If he is in fact global leader, “the selection of an Islamic State ‘caliph’ who, one, is not of Arab descent, and two, is based in Africa, would represent a notable change in tack for the terrorist organization,” according to a paper for the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point by Austin Doctor and Gina Ligon.

ISSOM formed in 2015 shortly after a subgroup of al-Shabaab members broke away, angered by the larger group’s refusal to switch its allegiance to IS. Nearly a decade later, ISSOM has about 500 members in Bari’s Cal Miskaat mountains. About half the members are from other nations: Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania and Yemen. Puntland authorities even arrested a few Moroccan nationals in 2023, the Crisis Group reported.

ISSOM’s entrenchment in Puntland is part of a larger trend of territorial gain for IS in Africa, according to Aaron Y. Zelin, a senior fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Years after IS lost ground in Iraq and Syria, it now has rooted itself in areas near Gao, Mali, Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado province and in Puntland’s Bari district.

The Somalia branch offers IS “a key node” in its global fundraising network, Zelin wrote, that connects African financiers with the Afghanistan branch known as ISKP. It is from there that most external IS operations are planned.

“These small pockets of control can have a larger impact if they enable IS to resume external operations, expand its financial activity, and disrupt global energy supplies,” Zelin wrote.

ISSOM’s resilience is due to three key things, according to the Crisis Group. The isolated mountainous area has little government presence, and coastal access makes smuggling and resupply easier. Second, regional clan connections also help. Finally, no one, including al-Shabaab, has been able to defeat ISSOM militarily.

“The main reason is probably that Al-Shabaab’s attention has been consumed by its war with the Somali government and allies,” according to the Crisis Group. Puntland’s government, claiming a lack of resources, has been ineffective.

Although ISSOM’s rivalry with al-Shabaab is an impediment to its growth, the al-Qaida affiliate has not been able to vanquish the group. Fighting between them, which began in 2015, has led to victories and defeats on both sides, according to the Crisis Group. The two sides remain at odds over competition for extortion opportunities and because some in ISSOM are al-Shabaab defectors.

To effectively combat ISSOM, Puntland political authorities will need to cooperate with those in Somalia and Somaliland on intelligence and applying military pressure. “The strains on Puntland’s relations with Mogadishu are particularly harmful, since Puntland is unlikely on its own to be able to tackle the IS-Somalia threat,” according to the Crisis Group. “These rival political centres and their respective security forces should seek to put these disputes aside and find a way to cooperate.”

To weaken ISSOM revenue streams, Puntland would do well to emulate Mogadishu’s efforts to curb al-Shabaab’s banking and mobile financial activity while building better relations with businesses to gather information and build trust, the group’s report said.

On the social and humanitarian front, Puntland could offer a route for defections to “provide a peaceful off-ramp for its discontented members” while also addressing community grievances where ISSOM operates. Looping in community leaders before military operations also would build trust, the Crisis Group said.