The Mwalimu Julius Nyerere Leadership School in Kibaha, Tanzania, looks like any institution of higher learning on the outside. Its campus shines with newness and embodies the spirit of Southern Africa’s six major liberation movements, which took part in its establishment.

Once inside its classrooms, however, a very particular and intentional type of instruction is offered, soaked in Chinese political doctrine and intended to “proselytize and methodically share” the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) governance model to build influence and gain allies on the continent, according to Paul Nantulya, research associate and China specialist for the Africa Center for Strategic Studies (ACSS).

The school is named for Tanzania’s first prime minister and five-term former president. His party and five others from the region co-founded the school. Those parties still rule Angola, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Tanzania and Zimbabwe. Together the six nations are part of the Former Liberation Movements of Southern Africa.

The school started with help from the CCP International Liaison Department, which provided a $40 million grant for its construction, Nantulya wrote for the ACSS. Chinese political functionaries from Beijing have taught there.

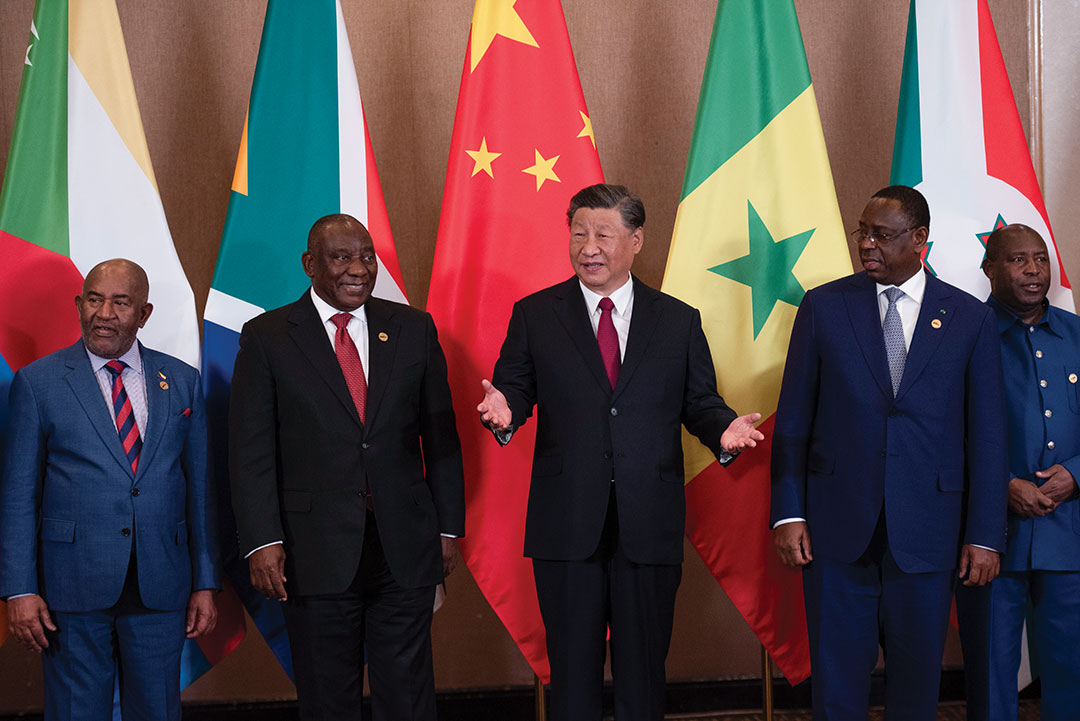

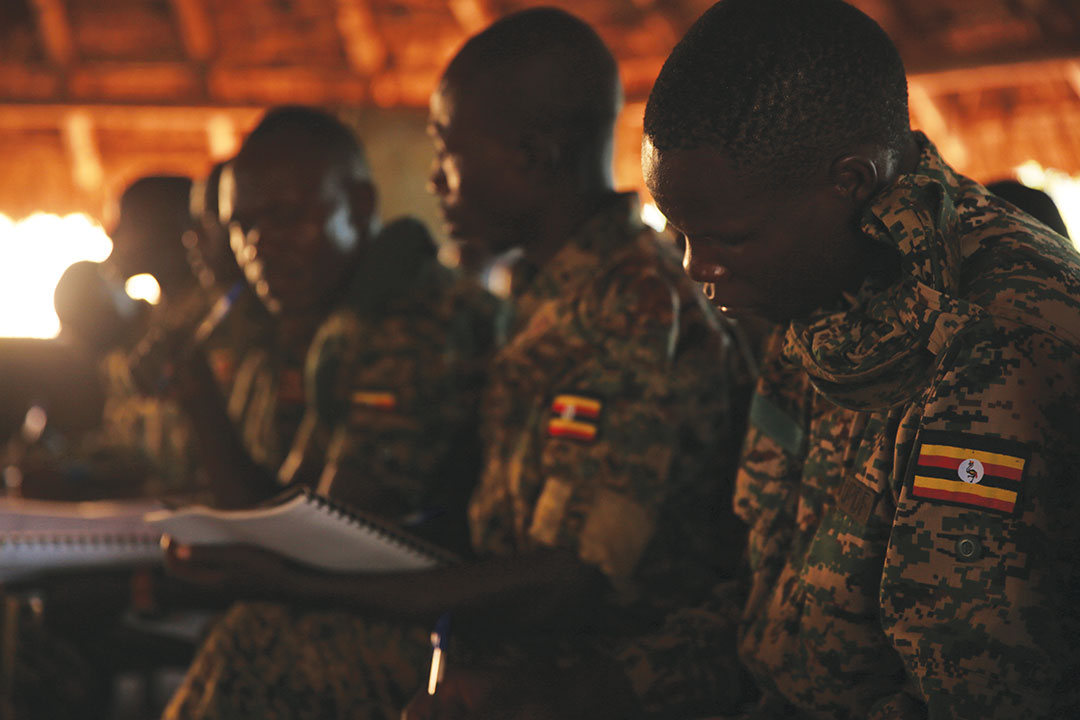

Through the Nyerere school, and others in China, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and CCP are trying to capture the hearts and minds of African military personnel to help tilt the global order toward China. Professional military education (PME) is just one part of China’s efforts to outsource its “party-army” model and secure military and political support across the continent.

“What China wants to achieve, more than anything else, is a foundation consisting of a consistently reliable, supportive constituent base,” Nantulya told ADF. This base would form a “foundation of constituencies of support that it can tap, recruit as and when needed to achieve the political objectives that are set by the CCP.”

getty images

A LOOK AT CHINESE PME

China always has approached engagement in Africa through political means rather than through displays of military commitment and power, Nantulya wrote for the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) in 2023. This contrasts with the former Soviet Union and Cuba. The former had six bases in Africa and supplied soldiers, advisors and heavy weapons. Cuba sent tens of thousands of troops to Angola and even participated in combat there.

China preferred a lighter footprint. Starting in Algeria in 1963, China sent medical teams to Africa each year. Each team consisted of between 25 and 100 civilian and military members who served two or three years at a time, Nantulya wrote. During the Cold War and beyond, about 40 such medical teams were operating in Africa at any given time.

Still, China’s most prevalent African engagement across the past 20 years is in PME, Nantulya wrote. Most of the engagement takes place in China at one of three types of schools:

Midlevel command and academic institutions, such as the command colleges attached to PLA service branches.

Specialized academic professional schools, such as PLA medical universities, China’s peacekeeping training center and its police peacekeeping training center.

Strategic-level schools such as the PLA’s National Defense University and its components.

At least 50 African nations take part in Chinese PME regularly — nearly 93% of all countries on the continent. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the PLA was educating about 2,000 African military officers each year at military and political academies, Nantulya wrote for the ACSS.

Chinese PME is noticeably different from Western teaching. In U.S. and other western military schools, class facilitators guide student discussions and encourage them to question things and use critical thinking to enhance their learning. They are not a “purveyor of the word,” Nantulya said. In fact, he said, some African officers are not accustomed to that freedom to critique and seek assurances that doing so is acceptable.

In Chinese PME schools, students are not allowed to question or criticize the Chinese system.

Chinese President Xi Jinping, who is chairman of the CCP Central Military Commission, noted that “the PLA was slowly developing an identity of its own outside the CPC and had to be brought back in line,” Nantulya wrote for USIP. In November 2014, at the All Army Political Work Conference, Xi noted 10 problems related to ideology, party loyalty and discipline, and issued new rules to “revitalize the ideological commitment of the PLA to party leadership, which sets the basic guideline for Chinese PME,” Nantulya wrote.

In classes for high-ranking officers, African students are segregated from Chinese personnel. African and Chinese officers will learn the same material but will do so on separate campuses, presumably to keep from exposing Chinese personnel to unwelcome ideas. “African officers also say that the quality of the programs at this level is lower than in the United States and United Kingdom on international issues, critical analysis, and national security strategy,” Nantulya wrote for ACSS. “In U.S. schools, African students work with their American colleagues and can critique their instructors and advance their own perspectives. This is not possible in the Chinese setting.”

“You can’t compare what I did here with what my colleagues did at PLA NDU,” an African alumnus of the U.S. Army War College told Nantulya.

afp/getty images

CHINA’S MILITARY MODEL

China’s military differs from Western forces in that it is a “party army,” not a national military. That means the PLA is an arm of the CCP, not the country. Other militaries, including many in Africa, are beholden to civilian control and national constitutions. Such militaries discourage member participation in party politics, considering it inconsistent with democratic values and proper civil-military relations.

Political functionaries within the Central Military Commission always lead PLA engagements with African countries. The commission is on par with departments that deal with training, logistics and other matters.

Politics always will be the tip of the spear when China engages with an African country. Political commissars will be at the forefront of any effort, whether it involves negotiating military equipment sales, training or PME. This is called “military political work,” Nantulya said. “The party-army work, the party-army orientation, the party-army model — it filters into everything that the PLA does when it interacts with others.”

China sees Southern Africa’s liberation heritage as fertile ground for the spread of its party-army philosophy. Zimbabwe already is known for having employed its military in service of its ruling party. Former Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe in 2017 co-opted a quote from Mao Zedong when he said, “politics shall always lead the gun and not the gun politics.”

Chinese PME, which often consists of classroom instruction and standard field training, advances party-army principles and influences African personnel in various ways. African attendees will learn about joint warfighting, troop organization, the use of artillery and other tactics, but that instruction will be subsumed by the political context and led by PLA officers steeped in political training and indoctrination, Nantulya said.

Conversely, many high-performing militaries use training models that stress the need for the military to remain apolitical and loyal to the nation’s constitution rather than a political party.

The Chinese model can erode democratic principles and proper civil-military relations, although the process can be subtle and slow. African delegations will see the political dynamic up front every time they interact with the PLA. That result likely would be in countries where there is a “legacy of latent behaviors that ascribe to the military a party-political role,” Nantulya said. China’s approach gives tacit approval to such tendencies. The approach is underscored by the countries the PLA prioritizes, such as Eritrea and Zimbabwe.

CHINA’S ULTIMATE GOAL

It’s no mystery why China has prioritized Southern Africa for the location of its one PME institution on the continent. But China has ambitions beyond that region. Indeed, China has built relationships through PME and training across the continent. Even countries that don’t share China’s revolutionary heritage are attracted to its PME purely for its accessibility. One thing China offers that many western nations can’t match is scale. China simply offers more classroom slots for African personnel to fill.

An African training officer told Nantulya that he is under pressure to train as many Soldiers as possible in five years to improve standards and reform the military. In fact, the officer said he sometimes struggles to fill the slots China makes available because he can’t afford to send that much human resource abroad at once.

China exploits that scale by training as many Africans as it can, sometimes engaging with the same people more than once over time.

China views the current world order as hostile to its ambitions. So, all over Africa and across South Asia and Latin America, China wants to build a foundation of support that it can leverage to help offer an alternative to the current system.

Its efforts are not limited to Southern African nations that share a liberation heritage, Nantulya said. China has trained hundreds of military personnel from across the continent, including democratic nations whose political values are at odds with China’s autocratic, political military philosophy. Where there is an opportunity to impart China’s ideological model, the PLA will use it.

Despite the thousands of African trainees, China needs only a small percentage — perhaps 2% per year — to go back home with a positive outlook about the country, Nantulya said. Just a few dozen well-placed people will make a difference and are just enough to infect an institution.

“They throw a lot into it, and then what happens is that over the years they identify those that continue to have this positive sentiment, and they keep inviting them back, they keep engaging them, they keep giving them opportunities, and so on,” he said.

The Chinese model begins as an extensive PME effort, but then it cascades and targets specific individuals.

This PME cycle is one cog in the gear of China’s influence engine. Soldiers and officers train in schools that push China’s ideology and doctrine. Simultaneously, China seeks political influence and financial leverage through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) infrastructure projects. As African governments depend more on China for both, some African military personnel might see opportunities to advance their careers, reinforcing a growing relationship with China. The circle of influence grows, and China can exploit it in multinational forums such as the United Nations.

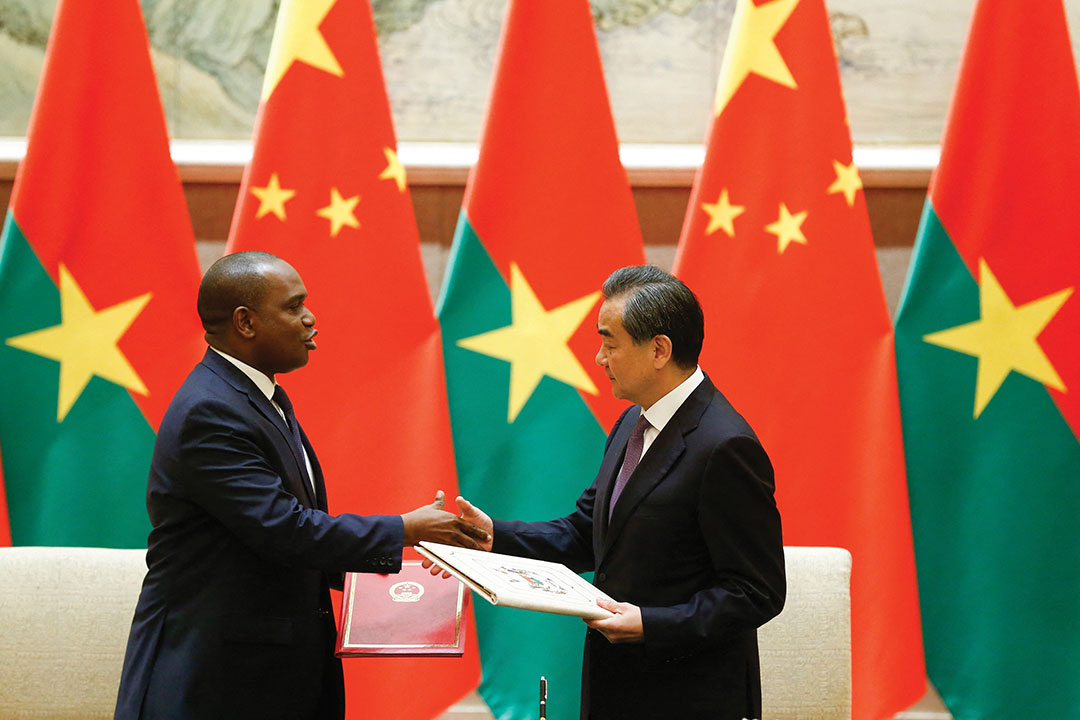

Burkina Faso provides an example. Several years ago, Burkina Faso sought help with infrastructure projects but did not have the money to fund them. China offered to bring the country into the BRI. But there was a catch: Burkina Faso would have to adopt China’s stance on the status of Taiwan, a prickly geopolitical matter. In 2018, after 24 years of diplomatic relations with Taiwan, Burkina Faso ended that relationship and recognized Beijing instead.

“Burkina Faso and China engaged in this dance, where China needed an ally, Burkina Faso needed finance, and so they were able to find each other halfway,” Nantulya said. “But after Burkina Faso signed this BRI agreement, then we began to see Burkina Faso soldiers going to China for military training. So, you can see how it works.”