Women Bring Value to Peacekeeping Missions, but Participation Hurdles Remain

ADF STAFF

Cpl. Laker Doris Patricia of the Ugandan People’s Defence Force drove a large supply truck every day. She carried everything from bullets to bombs. If she wasn’t twisting the truck’s huge steering wheel, she was on standby, ready to buckle up and trundle away. And she did it in the center of Somalia, one of the most dangerous places on Earth.

Maj. Gen. Kristin Lund of Norway spent two years as force commander of the United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus. She was the first woman to command a U.N. peacekeeping mission. In April 2018, she was serving as head of mission and chief of staff for the U.N. Truce Supervision Organization in the Mideast.

Priscilla Makotose of Zimbabwe is police commissioner of the United Nations-African Union Mission in Darfur, bringing with her 30 years of expertise, including police command positions. She was deputy director for administration in the Criminal Investigation Department of Zimbabwe Republic Police and served in the U.N. Mission in Liberia in 2005.

Lt. Col. Hoe Pratt of the Republic of Sierra Leone Armed Forces was the officer in charge of the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) Civilian Casualty Tracking, Analysis, and Response Cell in 2016. She is the first woman from Sierra Leone to serve in a peace enforcement mission. As head of the cell, she oversaw the monitoring of civilian casualties associated with the mission and worked to protect Somalis through preventive measures.

Lt. Col. Hoe Pratt of the Republic of Sierra Leone Armed Forces was the officer in charge of the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) Civilian Casualty Tracking, Analysis, and Response Cell in 2016. She is the first woman from Sierra Leone to serve in a peace enforcement mission. As head of the cell, she oversaw the monitoring of civilian casualties associated with the mission and worked to protect Somalis through preventive measures.

All over Africa and beyond, women are successfully prosecuting their duties in multinational peacekeeping missions. In AMISOM, women drive trucks, nurse the wounded back to health, patrol on gunboats, command combat battalions, and more.

The evidence is clear. Women can perform the full range of duties associated with peacekeeping. However, the numbers are disappointing. In AMISOM in 2016, women made up only 586 — less than 3 percent — of the more than 20,000 African troops deployed.

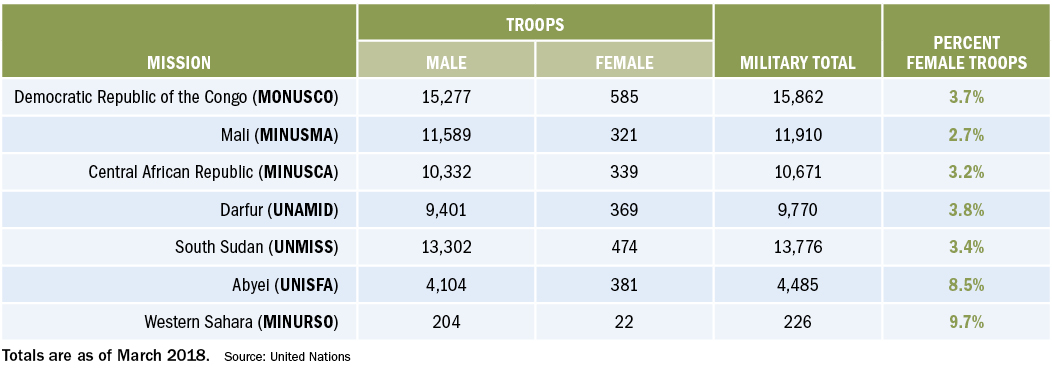

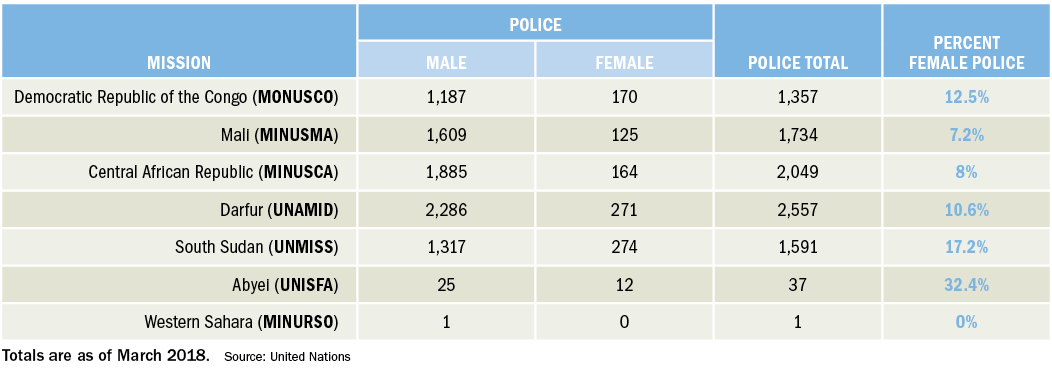

The numbers are not much better in U.N. missions. Based on March 2018 statistics, a mere 3.7 percent of all military peacekeepers serving in seven Africa-based missions are women. Globally, women represent about 4 percent of peacekeeping troops, which includes military experts and staff officers. Women fare a little better when it comes to the police ranks. In Africa-based missions, they make up 10.9 percent of all police officers. Globally, they represent 10.7 percent.

Although their ranks lag in these missions, their importance to them is undisputed.

THE VALUE OF WOMEN

Women have demonstrated that they can fill the same roles as men in military settings. They also can add an important dimension to peacekeeping operations.

“To begin with, women peacekeepers help missions build stronger relationships with communities and gain more access to information than all-male contingents can deliver,” according to a 2017 article for IPI Global Observatory. “They serve as role models, inspiring women in host countries to enter the security services themselves. Increasing the number of women in U.N. missions is also critical to ending a scourge of sexual exploitation and abuse by peacekeeping forces that causes tremendous suffering for its victims and diminishes the credibility U.N. peace operations globally.”

When mission personnel enter a country, they are charged with protecting all people, regardless of gender. In some countries, cultural and traditional norms prevent meaningful interaction between male peacekeepers and female civilians. As missions grapple with accusations of sexual misconduct by peacekeepers or armed combatants, the ability to engage effectively with women and children is vital.

Past conflicts more often involved one state at war with another, but that is less likely to be the case today. Most conflicts now involve insurgencies and nonstate actors battling state forces. This complicates responses and has broadened the definition and character of peace operations, wrote Nancy Annan and Serwaa Allotey-Pappoe in “Women and Peace Support Operations in Africa,” a chapter in “Annual Review of Peace Support Operations in Africa: 2016.”

“As new conflicts emerged, violence against civilians, especially women and girls, escalated with rape and sexual violence increasingly used as a weapon of war,” they wrote. It is because of these conditions, and others, that women’s participation in peacekeeping is vital.

“It’s very often the women peacekeepers who can establish the relationships with local women, children maybe, others, to reassure local communities on what we’re doing,” said Diane Corner, former deputy special representative for the U.N. mission in the Central African Republic, in a 2015 U.N. video. “I think it’s been shown time and again in terms of dealing with specific issues around sexual violence in particular, but possibly other human rights-related issues, that it’s better to have women.”

Women’s abilities and value are well-established. So why aren’t more serving in peacekeeping missions in Africa?

WHERE ARE ALL THE WOMEN?

Any explanation of why there aren’t more women in peacekeeping missions must start with troop-contributing countries. It must involve a number of issues, from political and social biases, to recruitment practices and the perceived role of women in a given society.

Despite these challenges, it is up to troop- and police-contributing countries to make sure that they have an appropriate balance of male and female personnel going to missions in line with United Nations and African Union requirements, Annan and Allotey-Pappoe wrote. When this happens, the results are apparent in the missions themselves.

Dr. Sabrina Karim, assistant professor in the government department at Cornell University, did several years of fieldwork in the recently completed United Nations Mission in Liberia. She observed that Ghana, which participated in the mission, has a high percentage of women in its military, due in part to a recruitment system that is friendly to women and includes leadership opportunities.

“So the argument then is that if you can get more Soldiers from these kinds of contributing countries that are doing something right, then that is going to make for a better overall mission,” she told ADF.

Of the seven active U.N. peace missions on the continent, only two have more than 4 percent women serving in military roles. The mission in Western Sahara has 9.7 percent women out of the 226 military personnel serving there. The mission in Abyei at the Sudanese border has 8.5 percent women serving in military roles out of 4,485, supplied almost exclusively by Ethiopia.

Missions in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Central African Republic, both well-known for incidents of sexual and gender-based violence, have 3.7 percent and 3.2 percent, respectively. Numbers of female police officers are appreciably better, ranging from 7.2 percent in Mali to 32.4 percent in Abyei.

So looking at recruiting is a good first step. But it can’t be just a numbers game. Simply adding more women to a peacekeeping operation will not ensure that their presence is helpful to the mission. Karim said her research shows that often women are not sent to the most dangerous missions or to missions where sexual violence is a problem.

FIRST, A GENDER ANALYSIS

Having more women will mean little to a mission if they are not deployed as part of a comprehensive gender perspective, said Sahana Dharmapuri, director of Our Secure Future: Women Make the Difference, a program of One Earth Future. All missions should perform a gender analysis to see how best to use men and women to achieve mission objectives.

Such an analysis can look at the broadest swath of mission objectives, such as the composition of civilian populations, and more detailed concerns, such as who uses a particular road at certain times. For example, when planning patrol routes for an area, a gender analysis might consider what road should be taken, then look at questions such as: What villages does this road go through? Who uses the road, and when do they use it? Does this road pass by a market? If so, when is the market open? Is it a women’s market?

Once mission planners have answers to such questions, they can decide the troop composition of their patrols. Although it might seem good to have an all-woman patrol visit the women’s market, Dharmapuri said mixed patrols are more effective. For example, having six mixed patrols might allow access to more places and people than one all-female patrol with six women in it.

Militaries do similar analyses all the time: Where should armored divisions deploy? Where are infantry or artillery needed? Adding the gender perspective to the overall analysis helps the mission succeed. “It should be integrated into your whole security picture,” Dharmapuri told ADF.

Striking the right balance regarding women’s service in these missions will require overcoming some misconceptions. In a 2014 article for the Alliance for Peacebuilding, Dharmapuri addresses what she calls “Three Myths About Women in Peacekeeping”:

“It’s all about women”: In fact, it is not. It is about providing security for all people — men, women, boys and girls. Including more women in the peacekeeping force and doing a thorough gender analysis on the front end helps make this possible. Dharmapuri stresses that men and women can adopt a gender perspective when serving in a mission.

“An equal number of female and male Soldiers in peace operations means we have achieved gender equality”: Not so. The goal is not necessarily to have equal numbers of men and women, but to have women serving as full participants at all levels of a mission and for men to be actively involved in promoting gender equality. This is especially needed since men hold many key military and political leadership roles.

“It’s all about sex”: Because of documented instances of sexual violence and abuse in missions, some mistakenly assume that the primary reason to include women is to deter this violence. However, women can do so much more. When conflict breaks out, men usually fight, and women are left to care for others. Mixed-personnel teams can train civilian women on other security matters, such as evacuations during disaster or conflict. Women should be seen as agents of change and stability, not just as victims, Dharmapuri said. “If you have parity, that alone is not going to change the gender bias and social behavior of the system,” Dharmapuri said. “The system is all of us. I think that’s the key thing that people forget.”