ADF STAFF

Amina Fofana is a member of one of Mali’s pro-junta protest groups and serves on the military government’s National Transitional Council, the nation’s legislative body.

She’s prolific on social media. Her Facebook page shows about 5,000 friends and is home to a torrent of posts that appear several times a day. She also is a staunch supporter of Russian influence in Mali and spreads its deceptive propaganda and disinformation.

On December 9, 2021, she posted a 3-minute, 27-second video that showed a white helicopter land in an open field as at least four young men waited. A voice narrated in Bambara as music played faintly in the background. One man got out of the helicopter and unloaded several bags and backpacks to the waiting men. One man took video of the encounter.

Fofana’s post claims that the video shows United Nations peacekeepers in Mali “supplying and moving the terrorists by helicopter from point A to point B!”

Nothing could be further from the truth. And yet the assertion is a common one in U.N. peacekeeping missions in the Central African Republic (CAR), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Mali. A common element in the CAR and Mali is the involvement of Russia-linked disinformation campaigns and the presence of a Moscow-backed private military force.

“In both CAR and Mali, the rise in disinformation against UN peacekeepers coincided with the deployment of Russian mercenaries from the Wagner Group in 2018 and 2021, respectively,” wrote Albert Trithart, editor and research fellow at the International Peace Institute, in November 2022. “While it is difficult to identify the origins of this disinformation, researchers have traced much of it to local civil society organizations or media outlets with financial ties to Russia.”

“In both CAR and Mali, the rise in disinformation against UN peacekeepers coincided with the deployment of Russian mercenaries from the Wagner Group in 2018 and 2021, respectively,” wrote Albert Trithart, editor and research fellow at the International Peace Institute, in November 2022. “While it is difficult to identify the origins of this disinformation, researchers have traced much of it to local civil society organizations or media outlets with financial ties to Russia.”

Ibrahim Togola, a Malian philosophy student and blogger, made short work of Fofana’s lies in a post for Benbere, a blog site that advocates for “reconciliation and appeasement of hearts for a united and open Mali.”

In his December 14, 2021, post he quotes the video narrator as saying: “They are the ones who kill our people. You say they are coming to help us […], they bring the equipment down to our bush to kill our rice farmers.”

The best hint that the video had been mischaracterized came from a Facebook user who lives in Bangui, CAR. In a comment on Fofana’s post, he pointed out that the helicopter was not a U.N. aircraft and was not even in Mali. In fact, it was in the CAR and sported an African Parks logo on the front. It was resupplying workers who manage the Chinko Nature Reserve.

African Parks is a South African nongovernmental organization, and an official there confirmed ownership of the helicopter and that it was on a routine resupply mission, according to Togola’s blog.

A LANDSCAPE OF LIES

As violence and political instability persist in the CAR, DRC and Mali, the atmosphere fills with disinformation and lies, much of it at the hands of Russian operatives and their allies. Identifying and effectively countering these lies is difficult, and U.N. officials have only recently begun to formulate coordinated responses.

Since about 2017, online disinformation against U.N. peacekeeping missions and individual peacekeepers in the CAR, the DRC and Mali has increased. “The most common false claims include that [peacekeeping missions] MINUSCA and MINUSMA are pillaging natural resources and colluding with armed groups or jihadists,” Trithart wrote, referring to missions in the CAR and Mali, respectively.

2022 saw disinformation decrease somewhat against MINUSCA in the CAR as it increased in Mali against MINUSMA, he wrote. The ramp-up in Mali would seem to coincide with the growing involvement of Wagner Group mercenaries and the withdrawal of French forces, who had been in the country for about a decade.

MINUSMA marks its 10th anniversary in 2023. As it does, it finds the challenges before it no less difficult than when it began. It remains the most dangerous peacekeeping mission on the continent. And although not the largest, it operates in one of the most inhospitable and challenging environments amid an array of violent extremist organizations.

Likewise, the CAR, also home to Russian mercenaries, remains dangerous amid lingering tensions between Muslim and Christian militias. In the DRC, more than 100 armed groups roam the eastern region, 1,500 kilometers from the seat of national government in Kinshasa.

Professional media outlets are scarce in these countries, leaving an “information vacuum” that provides fertile ground for disinformation and rumors, Trithart wrote. That combines with popular anger regarding the intractability of violence and the foreign intervention combating it. Rumors regarding COVID-19 and Ebola, particularly in the eastern DRC, have added to the problem and feed “into and off of” anticolonial sentiment and disinformation efforts.

THE U.N. TAKES NOTE

António Guterres pledged in 2016 when sworn in as secretary-general that the U.N. would “communicate better about what we do, in ways that everybody understands.”

In a July 12, 2022, address to the Security Council, Guterres acknowledged the perilous information landscape facing peacekeeping missions at the hands of bad actors.

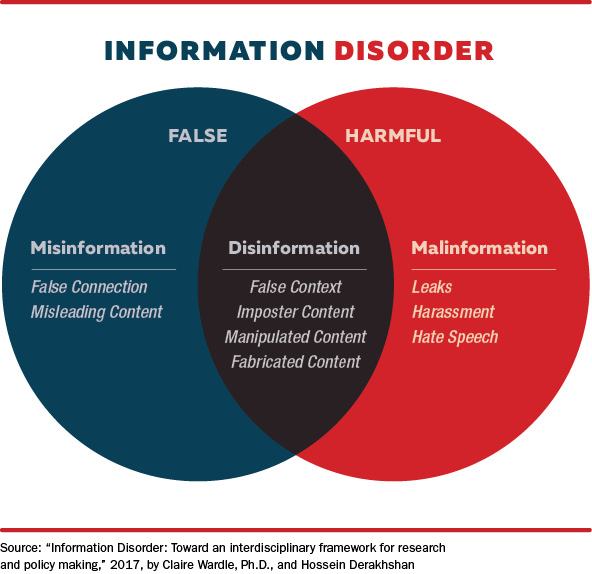

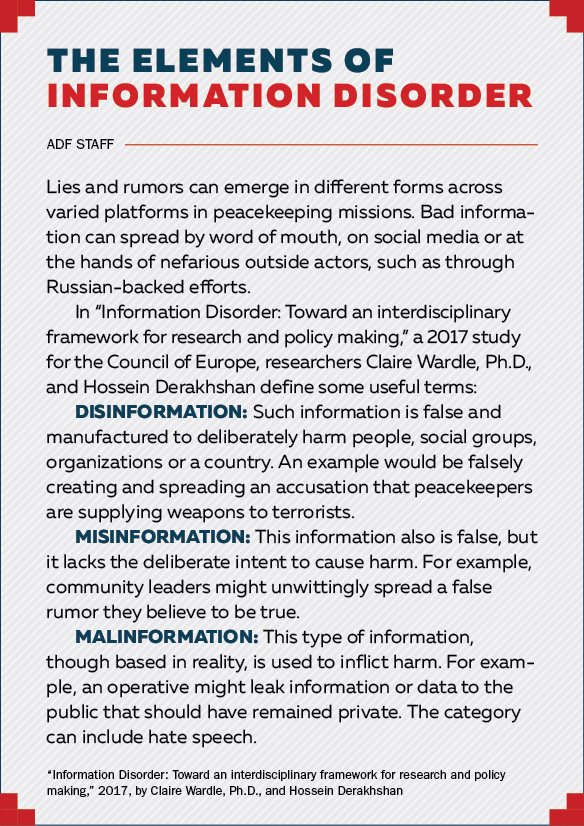

“The weapons they wield are not just guns and explosives,” Guterres said. “Misinformation, disinformation, and hate speech are increasingly being used as weapons of war” with a clear aim “to dehumanize the so-called other, threaten vulnerable communities — as well as peacekeepers themselves — and even give open license to commit atrocities.”

Guterres pointed to the need for effective strategic communications to protect civilians and peacekeepers. “Human-centered” strategic communication that helps build relationships is the “best, and most cost-effective” way to counter fake news and disinformation, he said.

“More than just defusing harmful lies, engaging in tailored two-way communication itself builds trust as well as political and public support … strengthens the understanding amongst the local population of our missions and mandates — and in return, strengthens our peacekeepers’ understanding of the local population’s concerns, grievances, expectations and hopes,” he said.

Several actions are ongoing to improve strategic communications in peacekeeping. The first is ensuring a “whole-of-mission approach” among uniformed and civilian personnel. Second, mission leaders are charged with ensuring that strategic communications are integrated into all planning and decision-making. Training and sharing of best practices will be provided to all missions, and tools will be deployed to counter disinformation, misinformation and hate speech. The U.N. also is continuously monitoring its information campaigns to make sure they remain effective.

Finally, strategic communications will enhance accountability and end misconduct, such as sexual exploitation. Such behavior can poison the information environment and turn civilians against peacekeepers. Disinformation and misinformation can fester and spread amid a lack of trust.

According to the International Peace Institute Global Observatory, an early 2022 survey of U.N. peacekeepers found that 41% said disinformation and misinformation “critically or severely impeded” mission mandates, and 45% said it similarly endangered peacekeepers’ safety.

COUNTERING DISINFORMATION

Guterres’ July 12, 2022, speech was the first time the U.N. Security Council had addressed strategic communications in peacekeeping operations, according to “Protecting the truth: Peace operations and disinformation,” an October 2022 study for the Berlin-based Center for International Peace Operations by Monika Benkler, Dr. Annika Hansen and Lilian Reichert.

The Security Council asked Guterres to produce a review of strategic communications across peacekeeping operations to “assess existing capabilities and impact on local communities, identify gaps and challenges, and propose measures to address them,” according to a U.N. news release.

In the meantime, however, missions have taken some actions on the ground to help improve the information environment and combat misinformation and disinformation.

In the CAR, United Nations Police (UNPOL) personnel conducted information sessions with civilian high school students in Bangui to explain the mission’s mandate and the work UNPOL is doing to support peace in the country.

Young people saw U.N. equipment and heard officials talk about the MINUSCA mission. Jean-Pierre Lacroix, the U.N.’s under-secretary-general for Peace Operations, hailed the effort on Twitter, saying, “Fighting #disinformation and #misinformation starts with young people.”

Such outreach can be valuable in equipping civilians, especially young people prone to heavy use of social media, to discern legitimate mission initiatives from rumors and lies.

In June 2021, MINUSCA invited editors and civil society leaders to Bangui for a session on combating disinformation. The Association of Central African Bloggers, the Consortium of Journalists Against Disinformation and the “Fake Check” Association of Central Africa were among those attending.

Serge Lambas, editor of Etoile newspaper, urged his journalism counterparts to respect the ethics of their trade. “As journalists, we must provide information with verified sources so that it benefits the population, in accordance with our professional ethics,” he said, according to a MINUSCA news report.

Thibaut Logbama Mokole, secretary-general of an association representing victims of disinformation, said, “After this training, we will go back to our respective bases to show our members how to use social networks, especially Facebook, and how to avoid publishing false information.”

As Africa’s population grows and becomes proportionally younger, it’s reasonable to presume that social media engagement will increase. As conflict continues in places such as the CAR, Mali and elsewhere, information vacuums will persist. The U.N., national governments and civil society organizations will have no choice but to continue addressing disinformation and misinformation.

Peacekeeping missions will have to develop new ways to counter disinformation to protect their own personnel, according to the Center for International Peace Operations report. It puts forth four areas for improvement:

SITUATIONAL AWARENESS: Missions should “map the media landscape” and monitor social media while also educating field personnel on disinformation. Conditions prone to disinformation, such as times leading up to elections, should be monitored for vulnerabilities.

RESPONSE: Each mission should have an overarching communication strategy that tailors approaches to groups vulnerable to disinformation. Mission personnel also should actively share verified, reliable information and “monitor human rights in the digital space.”

RESILIENCE: Missions must constantly analyze weak spots and respond as needed, while also regularly assessing information technology and communications to identify and monitor systems vulnerable to disinformation. Missions also should help host governments regulate online platforms and protect data. Building capacity and knowledge among journalists, young people and civil society representatives is essential.

COOPERATION: Missions should work with host nations and social media companies to appropriately regulate content and exchange information and best practices with other peacekeeping missions. Providing training for troop-contributing nations also would help.