ADF STAFF

The Ilemi Triangle is a sparsely populated, poorly demarcated tract of land on the border between Kenya and South Sudan. For years analysts have warned that this small, arid region has the potential to drive cross-border conflict.

However, Kenya and South Sudan are taking steps to define control over the Ilemi Triangle that could provide a model for how other African countries can resolve border disputes, experts say.

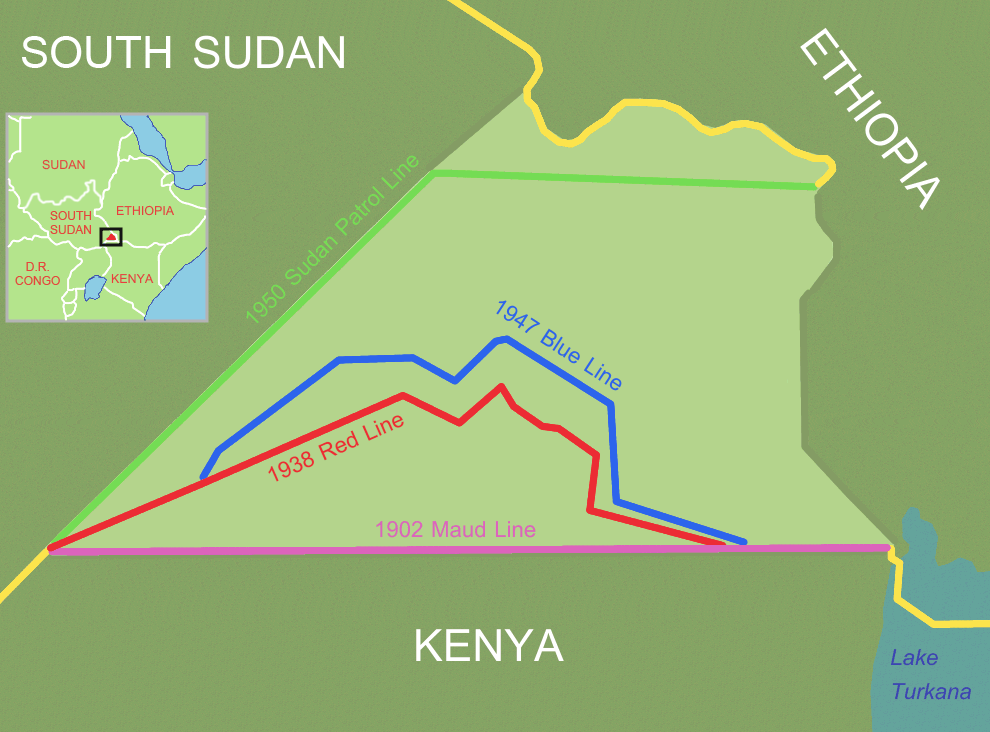

The Triangle, which covers between 10,000 and 14,000 square kilometers, is a legacy of poorly drawn colonial boundaries. Multiple surveys between 1902 and 1950 created four different configurations for the Triangle.

The earliest of those surveys, known as the Maud Line, gives all of the Ilemi Triangle to what is now South Sudan. Since 1928, Kenya has administered the triangle as part of its northwestern Turkana County. It does so now using the 1950 boundary, known as the Sudanese Patrol Line, which gives Kenya all of the Triangle.

For generations, the land has been occupied by Turkana pastoralists who have moved between the Ilemi Triangle and parts of Uganda. Today, the possibility that the Triangle area might have oil has increased the potential for conflict between Kenya and South Sudan.

The Ilemi Triangle is emblematic of border disputes across Africa that have turned into competition for control of resources — particularly oil.

In East Africa alone:

- Sudan and South Sudan dispute ownership of the oil-rich Abiyei region, a dispute that started 50 years ago and became a border issue when South Sudan gained its independence in 2011.

- Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo continue to debate control over parts of Lake Albert and surrounding area that could produce oil, diamonds, gold and coltan.

- Tanzania and Malawi are competing for control of land along Lake Malawi that could produce oil.

- Kenya and Uganda are in dispute over Migingo Island in Lake Victoria, partly for oil, but also for fish stocks there.

These and other boundary conflicts pose a challenge to regional politics and diplomacy, according to Al Chukwuma Okoli, a security expert at Nigeria’s Federal University of Lafia.

“Apart from creating diplomatic tension among states, the situation has resulted in a loss of lives and livelihoods,” Okoli recently wrote in The Conversation. “It has also destabilized the region — a setback to regional integration.”

Like the dispute over Abiyei, many of Africa’s border conflicts have simmered for decades without resolution. In many cases, the lack of a final resolution reflects the fact that nations want to avoid being perceived as losing territory or resources as part of a negotiated solution, according to Okoli.

Kenya and South Sudan agreed in 2019 to create a joint commission to resolve the conflict over the Ilemi Triangle and neighboring border regions. The commission launched in February 2023 after Kenyan troops responded earlier that month to an outbreak of violence between the Turkana and Taposa ethnic groups, which straddle the border with South Sudan.

In the process, Kenyan troops entered the community of Nakodok, a town that sits in the gray zone between the two countries. International maps show Nakodok in Kenya, but South Sudan also claims it based on a 2009 agreement inherited from Sudan to set a border outpost at Nadapal, 10 kilometers deeper into Kenyan territory.

Some residents and leaders of South Sudan’s Eastern Equatorial State protested the Kenyan action as an attempted land grab.

South Sudan Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs Deng Dau Deng told Voice of America (VOA) that his country has several areas where its borders are unclear, including with Uganda. He urged South Sudanese citizens to remain calm and let resolution efforts play out.

“We want to inform our youths to be calm, be patient. Your country is addressing all these matters,” the minister told VOA.

Nakodok lies in an oil-rich area just west of the Ilemi Triangle, but it demonstrates what is at stake in border disputes across Africa. The Kenya-South Sudan joint commission could show the way toward a peaceful resolution to that struggle and many others, according to Okoli.

“It is necessary to evolve a regional border management mechanism that can proactively and multilaterally address border-related issues to find an enduring resolution,” Okoli wrote. “The joint border commission between Kenya and South Sudan is a step in the right direction.”