As drones play a larger role in battle strategies across Africa, the continent’s militaries are adding small, commercially available drones to their arsenals as an inexpensive and highly adaptable alternative to military-grade unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs).

In recent years, African militaries have gone on a UAV shopping spree with Turkey’s Bayraktar TB-2 and Akinci drones becoming the most popular options. At $5 million each for a TB-2 and up to $50 million for an Akinci, the costs for cash-strapped militaries add up quickly.

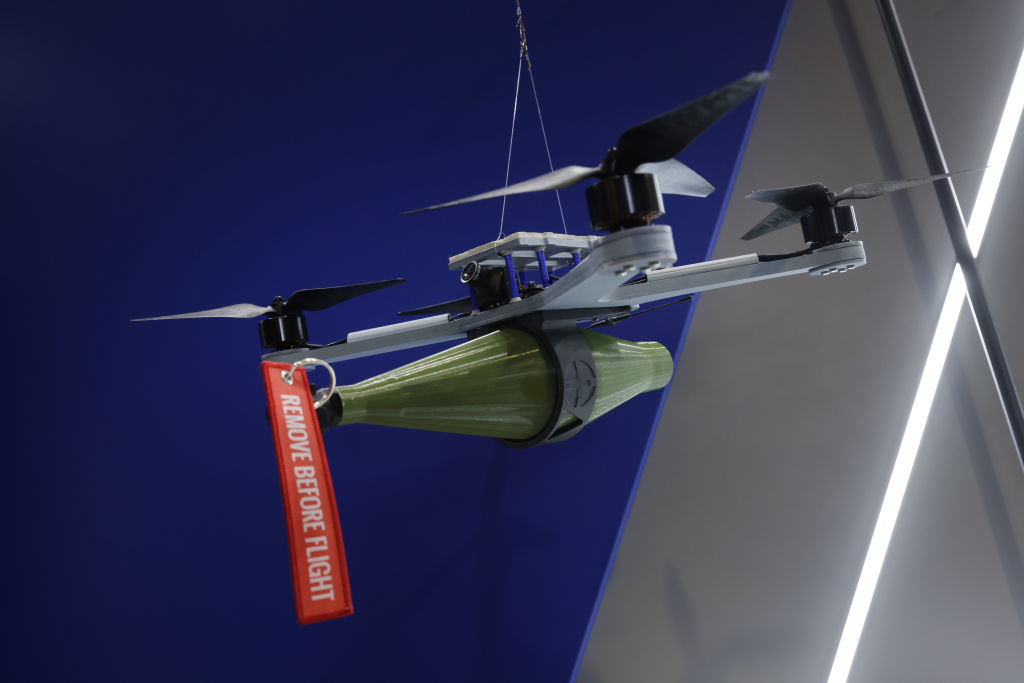

Commercial drones, by comparison, cost anywhere from a few hundred to a few thousand dollars and can easily be outfitted to carry small explosive payloads. The low cost makes them essentially disposable, analysts say.

The shift toward cheaper drones, many of them quadcopters, is happening partly in response to terrorists adopting the same technology. In recent years, terrorist groups such as al-Shabaab in Somalia and Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin in Burkina Faso and Mali have turned such drones into flying improvised explosive devices by mounting bombs to them.

Now, African militaries have adopted the same capability.

“They have this in their backpacks, they go for missions and they’re able to strike where necessary,” Muhammad Umar, chief technology officer at Nigerian drone-maker EIB Group, recently told Agence France-Presse (AFP).

Nigeria has become a leader in buying and building UAVs for military use. The Armed Forces of Nigeria have bought drones from a variety of suppliers, including Turkey and China, two of the biggest actors in Africa’s drone market, according to an Africa Center for Strategic Studies analysis.

Nigeria also is home to Terra Industries, formerly Terrahaptix, a robotics and manufacturing company that runs Africa’s largest drone factory. According to the company, the factory will be able to produce 30,000 drones a year, including long-range surveillance drones, quick-response quadcopters and small self-driving vehicles.

Since building its first drones in 2018, Nigeria has developed a kamikaze drone known as the Damisa in partnership with a Nigerian technology company. Nigeria and Ethiopia recently agreed to collaborate on a fleet of African-made drones capable of civilian and military applications. Ethiopia is the second-biggest drone buyer in Sub-Saharan Africa.

At a recent military expo in Nigeria, small drones were the star attraction — minus the ordnance. Vendors stressed the drones’ flexibility and rapid-response capabilities.

“You need speed, you need agility,” Oluwagbenga Karimu, a systems autonomy specialist for EIB Group, told AFP.

The UAV arms race also has the potential to harm civilians if there is not proper oversight and restrictions on drone use.

In Sudan, for example, a September 19 drone attack by the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in North Darfur killed 70 people attending Friday prayers at a local mosque. The RSF has launched similar attacks against hospitals in North Darfur. The Sudanese Armed Forces also have turned to small drones to attack RSF positions and civilian marketplaces that RSF fighters frequent.

Government-led drone attacks also have killed dozens of civilians in Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Mali, Nigeria and Somalia in recent years.

In a report published earlier this year, Drone Wars UK estimated that more than 940 civilians died in at least 50 drone-related attacks across six African countries between November 2021 and November 2024. Experts believe that estimate is well short of the real death count because many drone attacks happen secretly.

“Buying drones has become a cheap way for states to acquire significant firepower,” Michael Spagat, head of the department of economics at Royal Holloway, University of London, told Al Jazeera. “Drones have the additional advantage that attackers don’t have to worry about pilots getting killed. You don’t have to invest in training people you might lose.”

For analyst Cora Morris, who wrote the Drone Wars UK report, the rapid expansion of drones in warfare has harmed the civilians whom governments are supposed to protect.

“The mounting scale of civilian harm worldwide betrays a wholesale failure to take seriously the loss of civilian life,” Morris told Al Jazeera. “This is altogether more brazen where the use of drones is concerned with a concerning normalization of civilian death accompanying their proliferation.”