China has an extensive record of attempting to gain power and influence in Africa. Its media strategies seek to position it positively in the minds of nations and their people. It trains African military and police forces in the image of its own party-oriented model. Its professional military education centers instill its philosophy that “the party controls the gun.”

As these efforts continue, China is working to deepen its influence through the soft, subtle power of think tanks, in which ideas can join with political, security and economic policies in “shaping the global discourse” in China’s favor and “enhancing its influence,” according to a July 9, 2025, article by Samir Bhattacharya, associate fellow at the Observer Research Foundation.

“Despite the discourse of mutual learning, most of these forums are carefully orchestrated by China’s state apparatus, leaving limited space for open debate or critical evaluation of China’s development model,” Bhattacharya wrote. “Such asymmetrical exchange of ideas risks constraining authentic intellectual dialogue and limiting the scope for policy innovation.”

The idea of China using think tanks to influence African nations is not new. The effort goes back at least to October 2011, when China launched the China-Africa Think Tanks Forum (CATTF), which convened delegates from 27 African countries, Bhattacharya wrote. The forum has met 13 times since then. The most recent was in May 2025 in Kunming, China, where more than 100 delegates from Africa and China agreed to cooperate on governance and development.

China also has established scores of Confucius Institutes across the continent that serve as centers of Chinese culture, language and influence. But they have faced criticism over their lack of transparency and potential to be used for the spread of Chinese propaganda.

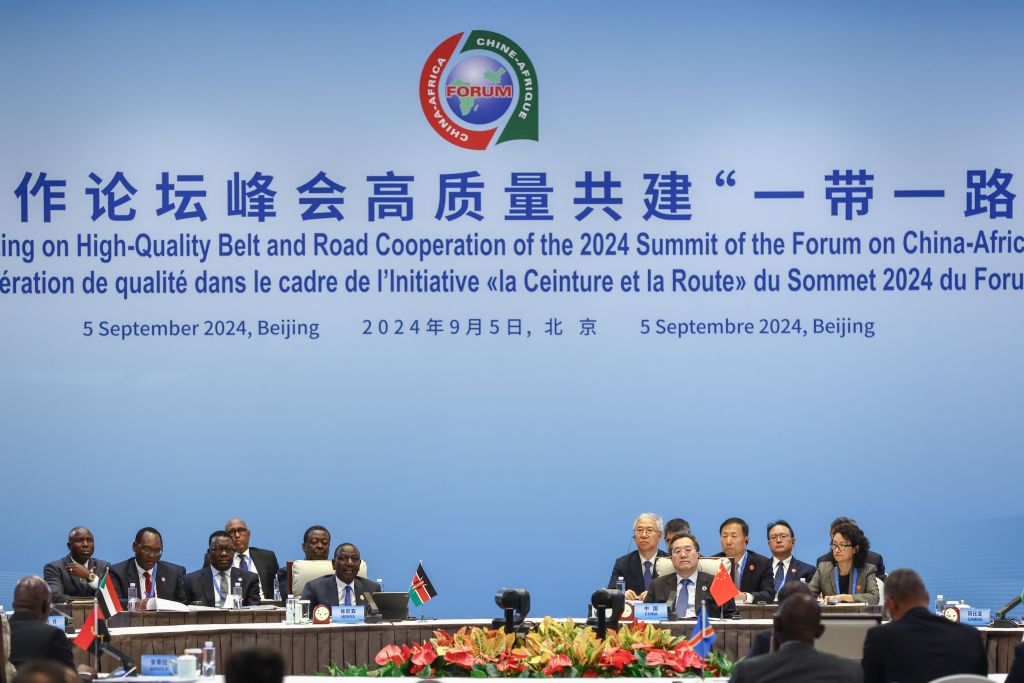

The CATTF is part of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), which met for the ninth time in September 2024 in Beijing. China welcomed Burkina Faso, Guinea, Mali, Niger and Sudan — all coup regimes — to the event, which “caused great discomfort (albeit quietly) among African participants, particularly since the [African Union] had reaffirmed the suspension of these juntas just prior to the summit,” Paul Nantulya, research associate with the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, wrote in October 2024.

FOCAC’s influence should not be underestimated. In 2021, Nantulya wrote that the 2018 FOCAC gathering saw 51 African presidents attend. Only 27 attended the United Nations General Assembly two weeks later.

On the surface, invitations to think thank discussion and seminars would seem to be a laudable way to build relationships, hash out ideas and reach policy accords. But, like China’s approach to security and military training, outcomes always are directed toward shaping African thought in the image of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Such was the case when China helped finance the Mwalimu Julius Nyerere Leadership School in Kibaha, Tanzania, to train African military personnel, Nantulya told ADF in 2024.

“What China wants to achieve, more than anything else, is a foundation consisting of a consistently reliable, supportive constituent base,” Nantulya said. This base would form a “foundation of constituencies of support that it can tap, recruit as and when needed to achieve the political objectives that are set by the CCP.”

During the 2024 Beijing summit, Chinese President Xi Jinping laid out his plans for China’s partnership with African nations. “In exchange, China expects African diplomatic support for China at the United Nations (UN) and other international forums,” Bhattacharya wrote.

An August 2024 article for the South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA) sets out how African countries can protect their interests while avoiding being drawn into complex geopolitical competition.

African nations could rely on regional bodies such as the AU to lead the continent’s relations with international powers like China. This could help nations negotiate development in settings such as FOCAC. “By presenting a united front through institutions like the AU, African nations can better leverage their collective bargaining power and ensure that development initiatives align with pan-African interests,” the article states.

Diversifying international partnerships will avoid an over-reliance on any one country, SAIIA asserts. African nations also should engage in ways that ensure tangible benefits for them.

African nations also can establish leverage through economic growth and development. Working through the African Continental Free Trade Area, part of the AU’s Agenda 2063 program to create the world’s largest free trade area, the continent can bolster its influence.

“For global powers, this means shifting towards less patronising partnerships that respect and address African interests and needs,” according to SAIIA. “They must move beyond viewing Africa solely through the lens of great power competition and instead focus on building mutually beneficial partnerships.”