Terror came to Benin in 2019. Sahel-based extremists emerged from Pendjari National Park and kidnapped two French tourists and their guide. Since then, a flood of incursions has bedeviled the country, increasing with each passing year.

Benin deployed 3,000 troops to the north under Operation Mirador to prevent militant attacks on civilians, security forces and park rangers in the W-Arly-Pendjari (WAP) Complex, which includes territory in Benin, Burkina Faso and Niger. Sahel-based militants have ramped up attacks on Benin and Togo and crept closer to Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, Mauritania and Senegal.

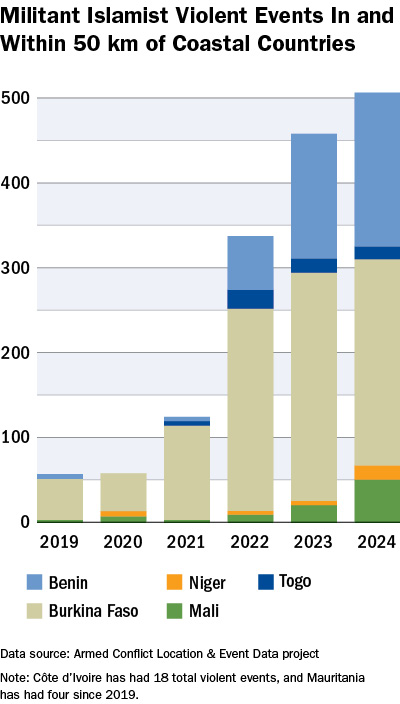

“The annual number of violent events linked to militant Islamist groups in and within 50 km of the borders of the Sahel’s coastal West African neighbors has increased by more than 250 percent over the past 2 years, surpassing 450 incidents,” according to researchers Daniel Eizenga and Amandine Gnanguênon in a July 2024 report for the Africa Center for Strategic Studies (ACSS).

That deadly trend continued on January 8, 2025, when militants attacked Operation Mirador forces, killing 28 Soldiers in the nation’s Alibori Department, which borders Burkina Faso, Niger and Nigeria.

“We’ve been dealt a very hard blow,” Beninese Col. Faizou Gomina, the national guard’s chief of staff, told the BBC. Gomina said the attacked position was “one of the strongest and most militarized” and called on commanders to bolster operations to prevent more attacks. The al-Qaida-linked extremist association known as Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) claimed responsibility. A military source told Agence France-Presse that Soldiers killed 40 militants in response.

“Wake up, officers and section chiefs, we have battles to win,” Gomina said.

A GROWING THREAT

Terrorist leaders met in Central Mali in February 2020 to discuss expanding toward the Gulf of Guinea, primarily through Benin and Côte d’Ivoire, and attacking military bases there.

French security officials said the meeting included leaders from al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb, Ansar al-Dine, JNIM and the Macina Liberation Front.

Since that meeting, the Sahel’s security has deteriorated significantly. A series of Sahel state coups in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger; the dismissal of Western security forces; and the overreliance on brutal Russian mercenary tactics all have led to worsened security. Attacks and deaths have steadily increased. Coastal nations have seen their border security fray, despite efforts to bolster it.

“The rapid westward and southward expansion of militant Islamist violence in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger in recent years has dramatically increased the number of violent events pushing up to and spilling over the borders of coastal West African countries from Mauritania to Nigeria,” Eizenga and Gnanguênon wrote for ACSS. “While most attention has been focused on Benin and Togo, there have been two dozen violent extremist incidents in Mali within 50 km of the borders of Mauritania, Senegal, and Guinea — in regions where, until recently, there was little to no activity.”

AREAS OF CONCERN

One of two hot spots is where Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire and Mali meet. Burkina Faso and Mali depend on Abidjan’s port for a significant percentage of national imports. Burkina Faso sends more than half of its exports through Abidjan, according to the ACSS.

The route also is laced with artisanal gold mines. The mines, trade routes and trafficking networks present attractive targets for extremists.

The 26,361-square-kilometer transnational WAP Complex presents a second source of peril to coastal nations, primarily Benin and Togo. JNIM-affiliated militants have infested the complex since 2018, according to the ACSS. Islamic State in the Greater Sahara has infiltrated the park from the Nigerien side. Extremists have aligned with regional smugglers who move cigarettes, counterfeit medicines and goods, fuel, gold, and guns through the parks, the ACSS reports.

Several major economic corridors pass through the WAP Complex, including Ouagadougou-Lomé, Niamey-Lomé, Niamey-Cotonou, Ouagadougou-Accra and Niamey-Ouagadougou. About two-thirds of Burkina Faso’s imports enter Benin through these corridors. The Niamey-Cotonou corridor handles more than half of Niger’s trade, according to the ACSS. Militants threaten all of these routes.

Amid these threats, coastal nations have taken actions to protect their sovereignty and keep vulnerable citizens from succumbing to extremism’s siren call.

Here are some of those efforts:

Benin has faced some of the most persistent threats, as underscored by the January 2025 attack. The creation of the Beninese Agency for Integrated Management of Border Areas has combined security and development in vulnerable areas.

Beninese authorities also reached an agreement with Niger in mid-2022 to fight extremism along their common border. However, a year later, a junta overthrew Niger’s democratically elected government and ended the agreement. Talks on a unified security and management plan for the WAP Complex also halted.

Between 2021 and 2023, Benin invested $130 million in its security forces, including an intelligence outpost in Pendjari National Park and eight military bases strategically placed across the parks, according to New Lines Magazine.

One such base in Kourou-Koalou sits where Benin, Burkina Faso and Togo meet and is equipped with heavy artillery and tanks, New Lines reported. Mirador’s 3,000-Soldier contingent is supported by an additional 4,000 who rotate through seasonally, the ACSS reported. Another 1,000 local forces help supply intelligence. All work with South Africa-based African Parks, a conservation group that manages Benin’s side of Pendjari Park and reserves.

Côte d’Ivoire has responded to the threat of cross-border attacks by fortifying its regional security presence and investing in socioeconomic programs. In 2022, the government launched the Program to Combat Fragility in the Border Areas of the North. It blends a heightened military presence with infrastructure investments and social programs aimed at young people.

The goal is to give young people in six northern regions tools to resist extremist appeals. For example, the program paid Samuel Yeo, a pig farmer in Ouaragnéné, 1 million CFA francs, which helped him more than triple his number of animals to 70. At one point, he was selling 10 heads for 150,000 to 200,000 CFA francs each month and growing two small eateries where he sold cooked pork.

Less than a year after its inception, the program had supported 23,892 people, according to a government report. The effort helped more than 30,000 beneficiaries in 2023. The program focuses on labor-intensive work, training, income generation, micro and small enterprises, subsidies to informal sector workers, volunteerism, and village savings and credit associations.

Côte d’Ivoire’s program is considered a success, and cooperative military operations between Ivoirian and Burkinabe forces in 2020 and 2021 provided “enhanced security, communication, and coordination across the border,” Eizenga and Gnanguênon wrote. But cooperation withered after Burkina Faso’s coups.

Togo initiated the Emergency Program for the Savanes Region to build resilience in its north. Between 2021 and 2023, authorities built a 25-megawatt solar power plant in Dapaong that brought electricity to 15,000 additional households, a regional increase from 29% to 42%, the Togo First website reported in January 2025. About 80,000 people gained drinking water access, an increase from 64% to 73.5%.

More than 1,000 hectares were developed, and an influx of modern equipment has made local farmers more productive and competitive.

An 18-month program to strengthen resilience against violent extremism in the Savanes region began in January 2024 with 5 million euros in European Union funding. The first of two projects will cover seven prefectures and help 10 local organizations start microprojects to boost employment, Togo First reported.

The second project targets two Central region prefectures. It will distribute health and school equipment to 10,000 people, financially support 4,000 women, and strengthen conflict prevention skills for 2,000 people, including local authorities. It will supply grants to 100 young entrepreneurs.

Although individual nations have worked to combat the extremist threat, Eizenga and Gnanguênon say enhanced regional coordination is necessary. They list several recommendations to help coastal nations:

Have security forces build rapport with civilians: Soldiers, police officers and customs personnel can’t merely be present in border regions. They must earn the trust of local people and respect their property. Security personnel will have to train in how to mitigate harm and work with communities. Heavy-handed tactics can destroy hard-won trust. Ghana’s Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre and Côte d’Ivoire’s International Academy for the Fight Against Terrorism can help.

Ramp up development in vulnerable areas: This is occurring already, and its success validates that efforts must go beyond military approaches. Countries successful in these efforts could help set up regional “development exchanges.”

Form a regional strategy on WAP Park Complex risks: Benin, Ghana, Nigeria and Togo should coordinate governing policies for borderlands and protected spaces. Countries must weigh security operations against efforts to preserve and protect communities’ livelihoods.

Streamline intelligence sharing: Nations should maintain open channels so security forces can swap information as extremists move. Assessments could be combined with information in the Economic Community of West African States’ (ECOWAS) Early Warning Network.

Adopt a multitiered stabilization strategy: The first layer could include boosting community resilience against extremist influences. Second, governments should support socioeconomic interests in vulnerable regions. Coordination and support from the Accra Initiative, a West African cooperative effort to blunt the spread of Sahelian terrorism, and help from ECOWAS in policy and financial matters round out the recommendations.

The rise of Sahel juntas has encouraged coastal nations to strengthen cooperation to meet the extremist challenge, Eizenga and Gnanguênon wrote. “Enhancing the cohesion, coordination, and scale of these coastal West African efforts to mitigate the threats may avoid a much larger and more costly regional impact.”