Amboma Safari and his family spent the night under their bed on April 11 as gunfire and bomb blasts echoed through the streets of Goma, the besieged capital of the North Kivu province.

“We saw corpses of soldiers, but we don’t know which group they are from,” he told The Associated Press.

As fighting continues to rage in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo between government forces, allied local militias and the Rwanda-backed M23 rebels, frustration with the disjointed Luanda Agreement peace process has gradually turned into pessimism.

After leading the peace process for nearly three years, Angolan President João Lourenço stepped aside as mediator on March 24, citing the need to focus on his role as chairman of the African Union. The AU appointed Togolese President Faure Gnassingbé as its new mediator on April 11.

On his way out of the peace process, Lourenço lamented a series of failed negotiations, broken ceasefire agreements and the years it took to convince Congolese President Félix Tshisekedi to agree to direct talks with M23, which he calls a terrorist group and a proxy of Rwanda.

“[We] worked towards this goal and secured the consent of both parties for the first round to take place in Luanda on March 18 this year. However, this event was aborted at the last minute,” his office said in a statement. M23 blamed international sanctions for its decision to reject the meeting.

The conflict has intensified since M23 launched an offensive in January and captured key towns in the North and South Kivu provinces, killing thousands, forcing millions to flee their homes, and worsening the region’s humanitarian crisis.

Attempts at peace talks have suffered from an array of obstacles, including disunity and confusion from multiple parallel attempts at mediation, funding issues, and external actors that have prevented the creation of a credible peacekeeping force to separate the combatants.

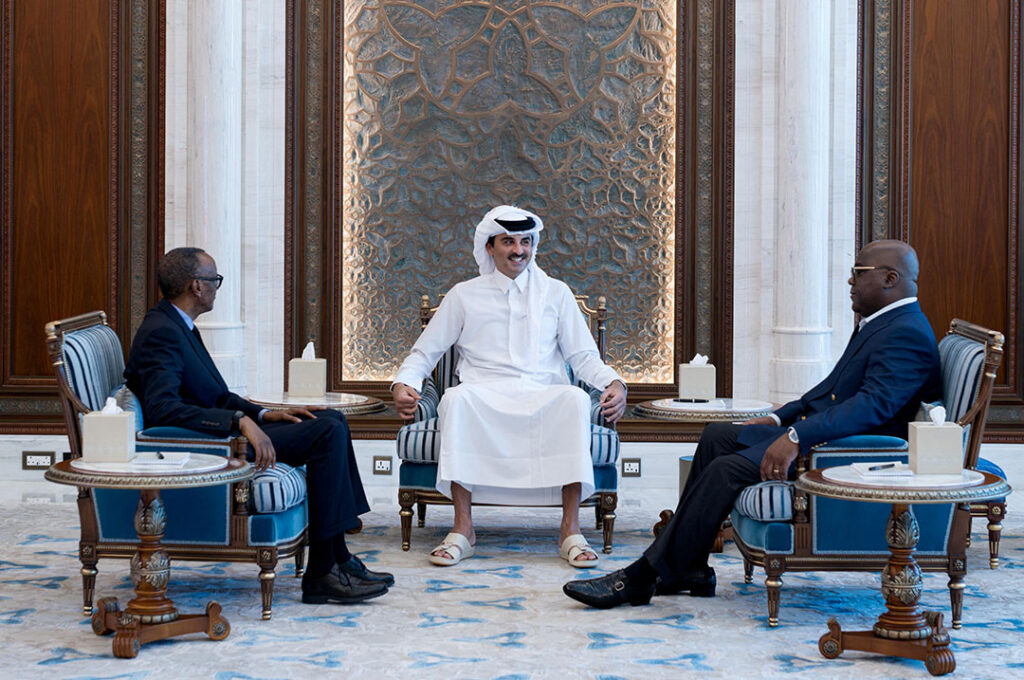

A surprise March 18 meeting in Doha, Qatar, saw Tshisekedi and Rwandan President Paul Kagame speak face to face and issue a joint statement calling for an “immediate and unconditional” ceasefire. A planned follow-up meeting for April 9 between DRC and M23 officials failed to materialize.

Onesphore Sematumba, a senior Congo analyst at the Crisis Group think tank, said that direct talks between the DRC and M23 would be far more significant than the meeting in Qatar.

“Let’s wait and see what will come next — Rwanda and the DRC have only laid the first stone on a long road,” he told Bloomberg News. “One should not be naive and think that Tshisekedi and Kagame are going to resolve their problems all at once. M23 is continuing to advance and gain more territory in every direction. Rwanda can always say that they were for a ceasefire, but they aren’t the belligerents.”

Despite signs of willingness to de-escalate from both sides, the AU peace process is in limbo until Gnassingbé’s first move, which will be supported by a team of mediators from the Southern African Development Community and the East African Community.

Congolese political analyst Bob Kabamba expressed concern about the clarity of the mandate for the new mediation team as well as its funding.

“The roles of this mediation have not been clearly defined,” he told Deutsche Welle. “The division of responsibilities is unclear. The issue of funding is also significant. Angola has spent a lot, and I don’t see any other country willing to step up and finance the mediation.”

Ghanaian policy and security analyst Fidel Amakye Owusu believes the peace process is complicated by the DRC’s wealth of natural resources, a border it shares with neighboring countries and the number of external influences.

“The DRC conflict is a very complex one,” he told DW. “It involves so many powerful individuals, so many powerful groups and institutions, and powerful countries, such as regional actors and international actors. The country is huge … and whatever happens there affects other countries.”

The most significant challenge for mediators, he said, is dealing with the dynamics and history between the Tutsi and Hutu ethnic groups: “Any mediator will find it difficult to really create a balance or work at a very fine line in this maze. And when the mediator over time does not see results, he or she will get frustrated.”