ADF STAFF

On a runway at an undisclosed location in South Africa, the Milkor company marked a milestone. On September 19, 2023, the Milkor 380, a medium-altitude long-endurance unmanned aerial vehicle, took to the skies for the first time.

The flight of the UAV, with a wingspan of 18.6 meters, put South Africa in an elite group of about 10 countries worldwide capable of producing a drone of that size and sophistication.

“This is officially the largest UAV that has ever been produced, developed, flown and tested on the African continent,” said Milkor Communications Director Daniel du Plessis.

With a maximum range of 4,000 kilometers and endurance of 35 hours, the UAV is ideal for intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) missions. With a payload of 220 kilograms, it also can carry weapons paired with a camera system to identify, track and engage a target and assess the mission afterward.

Perhaps the most exciting aspect of the launch is that 95% of the components of the Milkor 380 were developed locally. This is a major advance from previous generations of drones that relied heavily on foreign-manufactured parts.

“I think that’s one of the main things that makes this project so remarkable, is that many countries, be it developed or non-developed … they’ve struggled to put together the entire package of having a fully localized solution,” du Plessis said. “And we have done that.”

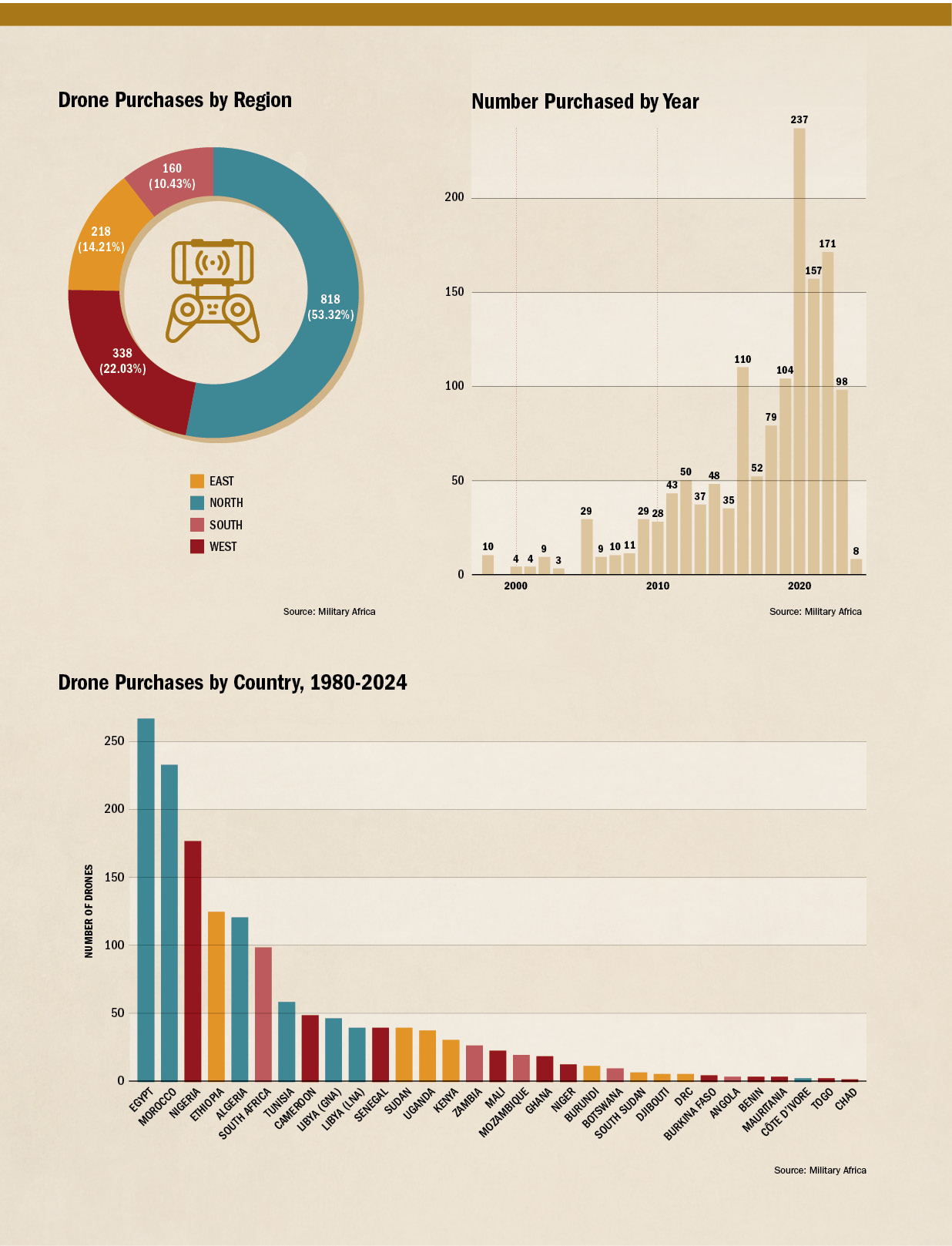

Milkor is not alone. The drone industry on the continent is booming with 13 African companies producing at least 35 models, according to data compiled by the security website Military Africa. Drones are used for border surveillance, to monitor poaching and illegal fishing, and to deliver medicine or other goods to remote regions. Advocates believe this growth in the drone sector will lower prices and allow African manufacturers to develop models suited for the unique conditions and security challenges of the continent.

But the rise comes with risks as well. In 2023, civilian deaths from drone and air strikes jumped to 1,418 compared to 149 in 2020, according to data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project. Extremist groups also covet drones. Al-Shabaab in Somalia, the Islamic State West Africa Province in Nigeria and terror groups in Mozambique have used off-the-shelf drones for surveillance and to make propaganda videos. Evidence shows that terrorists, particularly those linked to the Islamic State group (IS), plan to weaponize commercial drones.

Experts say the rise of the African drone sector must be matched by oversight, rules and safety measures.

“This democratisation of relatively affordable technology means that [drones] can be used for nefarious ends both in wartime and peace,” warned researcher Karen Allen, writing for the Institute for Security Studies (ISS). “The continent presents a vulnerable environment where weaponised drones may be tested and used by militaries and insurgents alike.”

A Need for Local Solutions

The first African-made drone emerged from research in the mid-1970s by South Africa’s government-funded Council for Scientific and Industrial Research and the defense manufacturing company formerly named Kentron. The Champion took flight in 1977 and was used by the military in the former Rhodesia for surveillance and later acquired by the South African Air Force.

At least 31 African militaries now operate drones with as many as 200 new drones added each year to military fleets. Domestically manufactured drones are still fairly rare, making up only about 12% of the total fleet. Leaders in the domain include companies in Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa and Sudan.

Ekene Lionel, the director of Military Africa, did extensive research on the industry and compiled a list of all UAV purchases by African militaries between 1980 and 2024. When studying trends, he found several factors pushing African countries to invest in domestic manufacturing capacity:

Cost: Local production can reduce costs associated with import taxes, shipping and currency exchange rates.

Cost: Local production can reduce costs associated with import taxes, shipping and currency exchange rates.

Customization: Domestic manufacturers can tailor drones to specific regional needs, climate conditions and operational requirements.

Self-sufficiency: Countries believe their national security is bolstered when they don’t need to rely on foreign suppliers for drones or drone parts.

Technology transfer: Building drones locally allows for knowledge transfer, skill development and technological advancements within the country.

Faster deployment: Domestically developed drones can be in the hands of security professionals and used faster than those ordered from abroad.

In his research, Lionel heard excitement and pride in the continent’s burgeoning drone sector.

“Perhaps the part that interests me the most is the fact that a robust domestic arms industry strengthens a country’s military deterrence,” Lionel told ADF. “By producing our own advanced weaponry, we can ensure a reliable supply, tailor equipment to our specific needs and maintain a state of readiness against potential threats.”

Lionel also believes drone technology, originally developed for security purposes, can spawn all sorts of new applications. Drones are being used for mapping, medicine delivery and spraying crops. The drone market is expected to triple between 2022 and 2031.

“Investing in local arms production creates jobs, fosters skill development and stimulates various industries, from manufacturing to research and development,” Lionel said. “Such efforts drive advancements in engineering, materials science and other high-tech industries, which can have spillover effects, benefiting other sectors of the economy.”

Defense Innovators

The private sector is leading the way in drone innovation, but in some cases, African militaries are getting into the research and development business. Nigeria’s Air Force Institute of Technology is the second-largest drone manufacturer on the continent and has produced 20 units since production began in the early 2000s, according to Military Africa.

In 2018, it unveiled the Tsaigumi UAV, developed in collaboration with Portugal’s UAVision. With its wing mounted above the fuselage, it can fly at heights of up to 4,600 meters and has a mission radius of 100 kilometers. It was created for tasks such as ISR, maritime patrol, pipeline and powerline monitoring, weather forecasting, and monitoring wildlife habitats for poachers.

Nigeria has logged the continent’s third-highest number of military drone purchases with 177 and is one of the few countries to host its own UAV pilot training school.

During the annual Africa Air Forces Summit in Abuja in 2024, Nigerian Air Marshal Hasan Abubakar, chief of Air Staff, said his country wants to be an innovation leader in the fields of UAVs, small arms, rockets and radar. He pointed to the recent establishment of the Air Vehicle Development Centre, which will allow the country to develop and manufacture aeronautic components domestically.

“To sustain its competitive edge in the ever-evolving security landscape, the [Nigerian Air Force] has embarked on a robust R&D drive to keep pace with emerging technologies and their application in modern warfare,” Abubakar said.

Morocco, which boasts the second-largest military drone fleet on the continent, also is looking to produce the aircraft. In March 2024, it announced it would partner with Israel Aerospace Industries and create a production plant to domestically produce UAVs. The facility in Rabat will produce WanderB and ThunderB models, which are primarily used for ISR, according to a report by Le Monde.

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE

The Danger of the Boom

Although the majority of UAVs being developed and built in Africa are for surveillance, armed drones also are on the menu. Nigerian manufacturers have two in the protype stage –– a six-armed helicopter UAV armed with a 250-kilogram bomb and an Ichoku tactical loitering munition. Egypt has built the armed EJune-30 drone, which can fly for 24 hours, and Sudan has built a Kamin-25 loitering munition drone.

Foreign-built weaponized drones have been used in conflicts in Ethiopia, Libya, Nigeria, Sudan and elsewhere.

Lionel said this aspect of drone manufacturing is bound to grow “exponentially” in coming years, and AI-enabled and semiautonomous drones produced in Africa might not be far off.

There is a looming danger that terror groups will acquire drones. In Somalia, al-Shabaab has used drones for surveillance and experts fear other groups plan to use drones to attack military and civilian targets. Cost is not a barrier to acquiring these tools. The most common drone used by IS in attacks in the Middle East is the DJI Phantom, which can be bought on Amazon for $400 to $500.

“What we’ve seen with small commercial drones is that, when utilized by otherwise underequipped, under-resourced, undertrained groups, those organizations are much more effective,” reporter Heather Somerville said in a Wall Street Journal podcast. “And they can wreak havoc on even strong sophisticated militaries.”

Allen of the ISS said governments must examine how to create registration systems for drones and mechanisms to flag the delivery of bulk purchases of hobbyist drones.

“While tighter regulations won’t necessarily prevent the nefarious uses of drone technology, they can provide early warning signs,” Allen wrote. “Given the broad applications of drones, it will need an approach in which government departments coordinate their responses.”

Militaries and police agencies also will need to develop strategies to protect vulnerable sites, including airports, energy plants and communications infrastructure. They will need to invest in counter-UAV technology to improve their ability to track drones in the air and shoot them down when they pose a threat.

“Personally, I believe it is an inevitability that nonstate elements would, in time, get their hands on commercially available drones, which they would weaponize,” Lionel said. “African security professionals should be proactive in mitigating this threat.”