BY CYRIL ZENDA

Talakufa Mudzikiti thought that the 1979 cease-fire ending Zimbabwe’s 15-year war would make it safe to search for his family’s lost cattle. It would end up being a costly adventure that he now regrets.

As he wandered the forests near Dumisa village in southeastern Zimbabwe, he stepped on an anti-personnel mine that blew off his left leg. “My life was destroyed that day … all my dreams were shattered,” he said. Mudzikiti, now 70, is not alone in suffering from the legacy of land mines used in armed conflict.

Mudzikiti and his fellow villagers are among more than 2,000 Zimbabweans who are maimed but alive. Nearly 1,700 others have been killed by land mines over the past four decades.

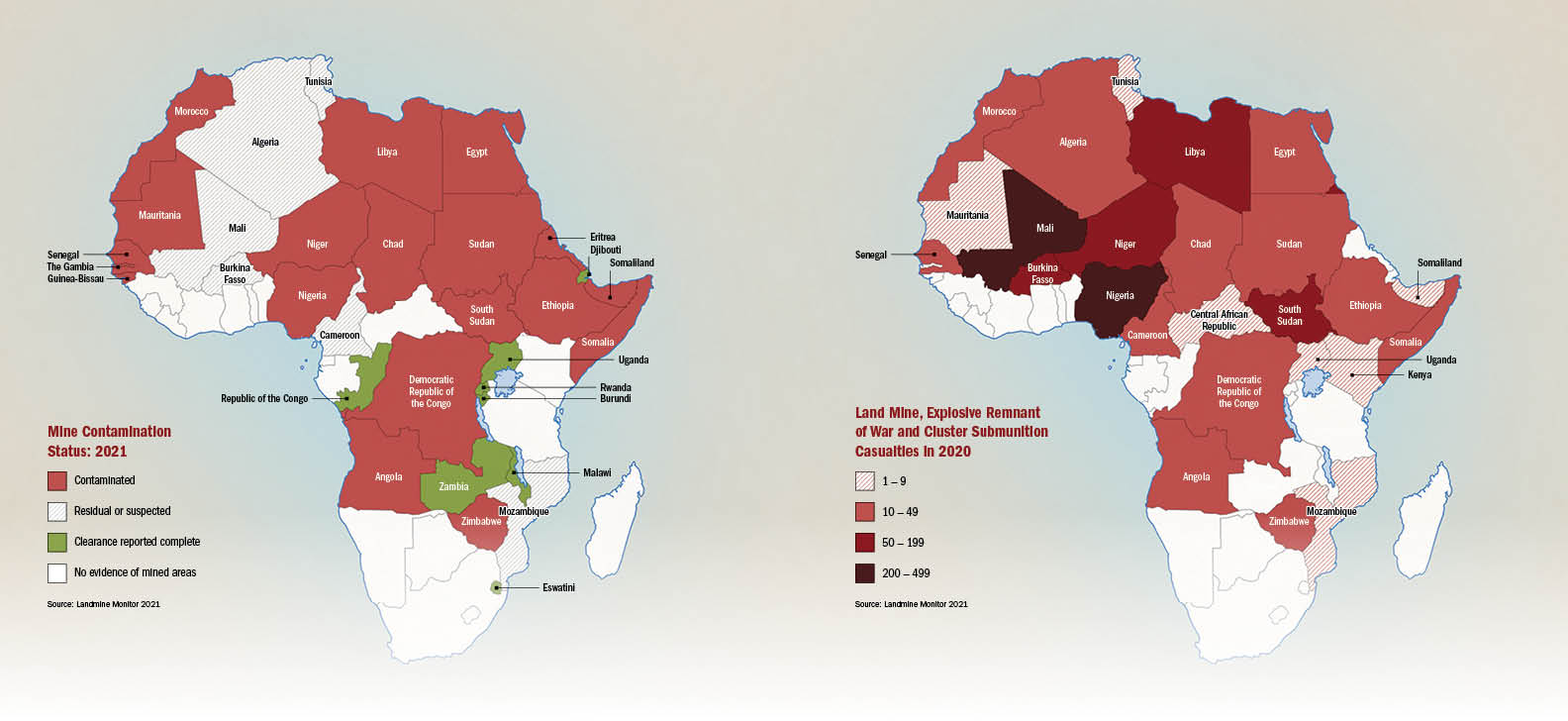

Dense Belts of Land Mine Contamination

Dense Belts of Land Mine Contamination

Zimbabwe, previously known as Rhodesia, gained independence in 1980, ending 90 years of colonialism and white minority rule. The 1970s were marked by a brutal bush war that killed more than 50,000.

To deter liberation fighters entering the country from neighboring Mozambique and Zambia, the Rhodesian army planted an estimated 3 million anti-personnel mines between 1974 and 1979 in five major minefields across 850 kilometers of the country’s eastern and northern borders.

Dense belts of land mines — some with about 5,500 per square kilometer — on Zimbabwe’s border with Mozambique have hindered development in marginalized communities.

As of September 2018, mines were thought to dot more than 66 square kilometers of land. A survey of Zimbabwe’s northeastern region identified 87 communities containing more than 75,000 people directly affected by mines.

The survey also found that 78 minefields were within 500 meters of residential areas.

The land mines block access to residential land, inhibit cross-border trade, deny small-scale farmers access to agricultural land, separate communities from primary water sources, and adversely affect sanitation and livestock production. As a result, most affected areas have disproportionate levels of poverty and high rates of food insecurity.

National Mine Action Strategy

As a party to the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention, the government of Zimbabwe is committed to working toward meeting the 2025 target of making the country free of land mines by putting into operation the National Mine Action Authority of Zimbabwe, a policy and regulatory body for mine action in the country. Reporting to the authority is the Zimbabwe Mine Action Centre (ZIMAC), which coordinates the country’s demining activity. In 2018, Zimbabwe launched its National Mine Action Strategy 2018-2025.

Zimbabwe has five demining missions: the Zimbabwe National Army’s National Mine Clearance Unit, HALO Trust, Mines Advisory Group, the Norwegian People’s Aid (NPA) and Belgian-registered APOPO, or Anti-Personnel Landmines Removal Product Development.

Sten-Trygve Brand, advisor for Mine Action and Disarmament at NPA, said the organization’s mine clearance work has directly benefited more than 70,000 people in Zimbabwe.

“We have been part of the humanitarian demining efforts in Zimbabwe since 2012 … and currently operating with five demining teams and one MDD [mine dog detection] team,” Brand said by email.

NPA has been working in three minefields with a total size of 16.7 square kilometers on the eastern border with Mozambique, namely Leacon Hill to Sheba Forest, Burma Valley and Rusitu to Muzite. Of these, the Burma Valley minefield was cleared and handed over in 2015, protecting 253 households. At the end of 2020, NPA had destroyed 26,982 anti-personnel mines and was left with an estimated contamination area of 7.2 square kilometers, which it intends to have cleared by 2024.

“Clearance and land release along the border have enabled communities and authorities to engage in activities such as border control, farming, access to clean water, attending schools in closer proximity to their villages, grazing livestock, as well as cross-border interaction without the threat of accidents, which may result in loss of a limb or life,” NPA said.

HALO’s work clearing land mines is focused in the nation’s northeast, where it has been working since 2013 and has destroyed more than 100,000 land mines.

“Staggeringly, that’s nearly four land mines for every person in that part of the country,” the organization said. “Last year alone, HALO’s team in Zimbabwe cleared nearly 10% of all land mines destroyed around the world.”

Endangered Wildlife Also Killed

Endangered Wildlife Also Killed

In addition to the human death and injury toll, anti-personnel mines have killed more than 120,000 cattle. The mines also have killed countless numbers of wild animals such as elephants, rhinos, lions and giraffes. Some of the minefields extend into the Gonarezhou National Park, which is part of the three-nation Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park. The larger park includes parts of Mozambique, South Africa and Zimbabwe, and allows for the free roaming of wildlife.

APOPO started demining work in December 2020 along the Cordon Sanitaire minefield that affects the Sengwe Wildlife Corridor in the southeastern part of the country. It intends to find and destroy about 15,300 land mines and clear 7.23 square kilometers.

“APOPO believes that it should be able to complete the task by 2025 or before with consistent donor support,” the organization said.

“By clearing the land mines, APOPO can lay a strong foundation for communities to rebuild their lives and for agriculture and ecotourism to return and thrive, bringing many benefits to the nation as a whole.”

Financial Constraints Delayed Clearance

The Zimbabwe National Army declined a request for comment. It is known, however, that financial constraints have hindered demining efforts. According to ZIMAC’s revised mine action work plan for 2020-2025 submitted to Mine Action Review, $65.6 million is required by the mine action program to meet its extended deadline of 2025.

ZIMAC informed Mine Action Review that the economic downturn in 2018 likely would limit the government’s potential to increase any funding for mine action, although it expected annual funding levels of $500,000 to be maintained.

The financial challenges facing the Zimbabwean Army have in the past been confirmed by Defense Minister Oppah Muchinguri-Kashiri, who said the Army has been lacking funding even for basic operations.

Villagers Grateful, Hopeful

“We are happy with the demining process which is taking place, but government should find a way of compensating us,” Mudzikiti said in an interview. His sentiments are shared by other victims and family members of those killed.

Lisimati Makoti, who is Chief Sengwe in the Chikombedzi area, commended the land mine clearing exercise and said it is a noble initiative because his people had continued to suffer long after the war ended.

Lisimati Makoti, who is Chief Sengwe in the Chikombedzi area, commended the land mine clearing exercise and said it is a noble initiative because his people had continued to suffer long after the war ended.

“We are grateful of this demining exercise,” he said. “It was long overdue because my people were living at risk of losing their lives to land mines. … Many have also lost their livestock to the land mines.” q

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Cyril Zenda is a journalist based in Harare, Zimbabwe. His work has appeared in Fair Planet, TRT World Magazine, The New Internationalist, Toward Freedom and SciDev.Net.