ADF STAFF

Larba Mathieu Yougbare hunched over as he tried to loosen the firm, dry soil with a small hoe. Frustration was as evident on the farmer’s face as beading sweat.

He returned to the eastern Burkina Faso city of Fada empty-handed.

“The harvest is bad,” he told the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) earlier this year. “We came here because we were forced to flee our village. Our fields in the village are more fertile than those here.”

Yougbare was given a small plot to work near Fada, but his efforts have yielded few rewards.

Hunger stalks refugees in one of the most violence-plagued parts of the world.

He is one of 1.8 million Burkinabe, nearly 10% of the population, who have fled their homes in search of safety. Like 80% of people in the country, Yougbare relies on agriculture for his livelihood.

Just as it has engulfed the Sahel region, a seemingly intractable insurgency has overrun Burkina Faso. Vast swaths of land remain outside of government control.

The Sahel exemplifies how food insecurity has risen sharply across Africa.

Experts say terrorism and war are the predominant causes.

“Violence in the Sahel is not only fueling the food crisis, in many places it is instigating one,” ICRC Africa Director Patrick Youssef said in a statement. “The situation is critical, and the [post-harvest] lean period could spell catastrophe if a concerted effort is not made to assist the millions of people affected.”

Around 346 million people on the African continent face severe food insecurity, according to a United Nations assessment in May.

“Most affected are countries that are in armed conflict,” Youssef said.

There are many root causes of hunger in Africa: poverty, the COVID-19 pandemic, the loss of basic services, and Russia’s war on Ukraine in the region of eastern Europe known as “the world’s breadbasket.”

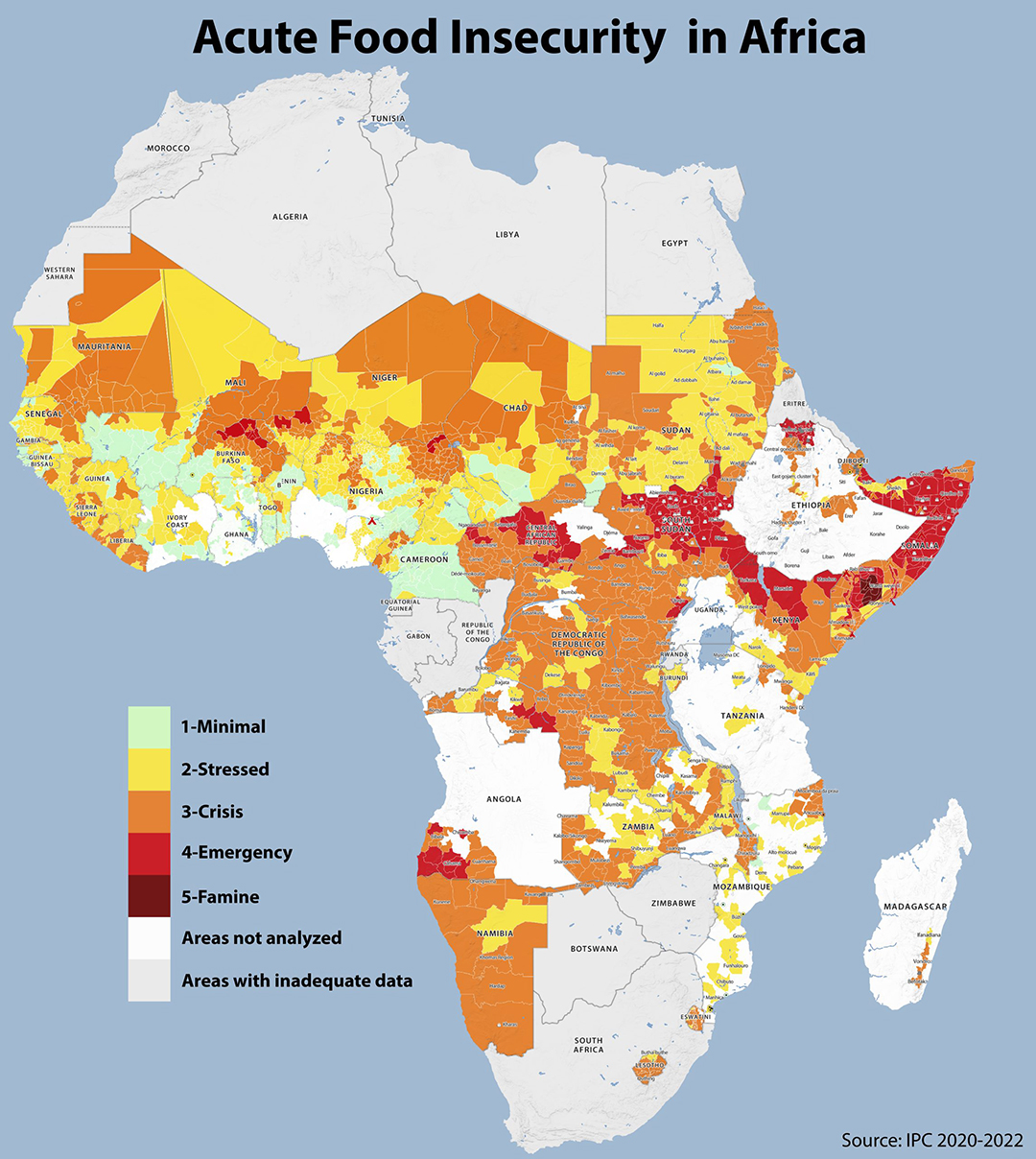

But the deterioration of security tops the list. In fact, maps highlighting regions that are dealing with severe hunger look similar to maps of regions with active armed conflicts.

In their jointly published October 2022 to January 2023 outlook, the U.N.’s Food and Agriculture Organization and the World Food Programme (WFP) raised alarm.

“Organized violence and armed conflict remain the primary driver of acute food insecurity across regions and in the majority of the hunger hotspots,” it said. “This reflects a global trend where conflict continues to affect the largest share of people facing acute food insecurity.

“Key trends indicate that conflict levels and violence against civilians have continued to steadily increase in 2022.”

Already in a fragile situation, displaced people are extremely vulnerable to food shocks. Often, families and whole communities who flee violence depend on humanitarian aid to survive.

Millions of people are stuck in areas that aid organizations cannot reach because of insecurity.

In Burkina Faso, the ICRC reported dire situations in the towns of Djibo, Kelbo, Madjoari, Mansila and Pama.

“Confined to increasingly tighter spaces and unable to flee, these people are facing a major food crisis on their own,” the organization said.

The U.N. and WFP listed Ethiopia, Nigeria, Somalia and South Sudan on the highest alert level of the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) scale, saying, “they all have populations facing or projected to face starvation.”

The IPC scale of 1-5 ranges from minimal to stressed, crisis, emergency and catastrophe.

African nations comprise 11 of the 19 world “hunger hotspots” listed in the FAO/WFP quarterly outlook.

More than 70% of African people facing crisis or worse (levels 3-5) food insecurity in 2021 were living in conflict‑affected countries, according to IPC data.

Those figures increased 22% in 2022.

The four African nations at level 5, or the catastrophe phase, are wracked with violence.

Ethiopia’s civil war with its Tigray region has been the world’s bloodiest conflict for the last two years. Parts of Nigeria remain in the grip of multiple terror groups and rampant banditry. South Sudan is plagued by intercommunal violence. Somalia has been at war with an al-Qaida-linked insurgency for more than a decade.

The Sahel is another major hotspot in terms of terrorism and food insecurity.

In the Liptako-Gourma tri-border region, the ICRC reported “80% of cultivatable land has been lost in more than 100 villages as crops are destroyed and people forced to flee.

“Our post-harvest monitoring in the provinces of Yatenga and Loroum in Burkina Faso have shown yield losses up to 90%.”

U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres made an urgent call for action on the intertwined crises during a Security Council meeting in May.

“When war is waged, people go hungry,” he said. “Let there be no doubt: when this council debates conflict, you debate hunger.

“When you make decisions about peacekeeping and political missions, you make decisions about hunger. And when you fail to reach consensus, hungry people pay a high price.”