ADF STAFF

There’s a fantastic amount of gold to be found in the Sahel.

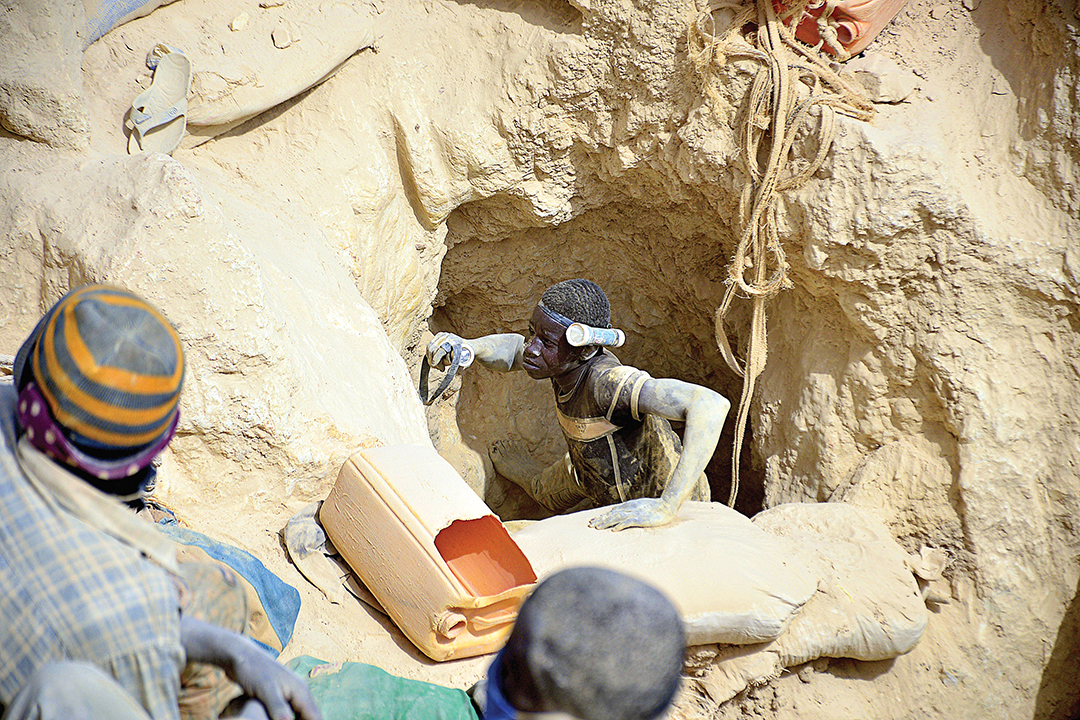

In addition to the region’s large-scale industrial mines, there are small artisanal mines — hundreds of them in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger — with people, including children, mining gold with simple hand tools. A 2019 International Crisis Group report said that more than 2 million people in the three countries work in small-scale artisanal mines.

With so many mines and miners, the three countries can’t protect them from attacks and raids by terrorists and robbers.

The region has become the center of a surge in terrorism, with thousands of people killed and millions more forced to flee their homes. Huge areas of the three countries are left ungoverned and unpoliced.

As the violence spreads, it threatens other countries, including the coastal states of Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana and Togo.

Ayisha Osori, head of the Open Society Initiative for West Africa, told the Financial Times that if terrorists destroy security in the Sahel, there will be “a domino effect of insecurity, wholesale violence … breakdown of borders as internally displaced persons spread across the Sahel” and beyond.

The terrorists’ tactics range from providing paid protection to small mines to all-out invasions of mines and mining towns.

For extremists to expand and hold their territory, they need money, and the artisanal mines in Burkina Faso alone are believed to produce as much as 30 metric tons of gold per year. The artisanal mines are generally in remote areas, away from government taxation — and protection.

The gold from the artisanal mines, according to the Financial Times, usually is smuggled to neighboring Togo, where it is taxed at a lower rate than in Burkina Faso. From there it is flown to the United Arab Emirates for processing. The gold typically is transported in hand luggage and flown on commercial flights. A 2018 study indicated that about 20 metric tons of gold makes its way from Burkina Faso to Togo each year.

The region’s artisanal gold mines serve the extremists in more ways than just money. The miners themselves are poor and working under terrible, and dangerous, conditions. Extremists often recruit them. Many of them are just children, mostly boys, open to manipulation.

Artisanal gold mining often involves the use of explosives such as dynamite, and extremists have used some of the mines to train recruits in the use of dynamite as a weapon.

The region’s terrorists have not limited their attacks to just small, artisanal mines. They also have attacked trucks and convoys used by large mining companies. In Burkina Faso on October 29, 2021, terrorists attacked a convoy of buses and supply trucks carrying 33 employees and contractors of the Canadian mining company Iamgold. It was the second such attack on an Iamgold convoy in three months, The Globe and Mail newspaper reported.

TWO MAIN GROUPS

There are two main groups of extremists operating in the Sahel. One is Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (Group for the Support of Islam and Muslims, or JNIM), a coalition of insurgent groups that formed in 2017. Since then, it has expanded its operating territory across West Africa while waging war against civilians, local security forces, international militaries and United Nations peacekeepers.

Researcher Jared Thompson, writing for the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said JNIM has successfully tapped into local grievances in expanding its territory, “while responses to the insurgency have not addressed the political drivers of conflict and have facilitated human rights abuses.”

“Attacks on security forces and violence against civilians by JNIM are both likely to continue as insurgent violence inflames community tensions and political dynamics between Sahelian states and international partners impede a comprehensive pathway to peace,” Thompson noted.

The other group is the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), an Islamic State group affiliate. It has been particularly violent against civilians, local authorities and international security forces. “The group will likely continue to pose a threat to local communities and Sahelian states as counterterrorism efforts alienate civilians and fail to roll back ISGS’s territorial gains,” Thompson noted in a July 2021 report.

The two groups have similar goals, including imposing strict Shariah. Miners have reported that extremists have shown up at their mines and directed them to grow their beards, shorten their pants and conduct daily prayers. Both groups exploit community tensions and the failure of governments to intervene and provide security. Both take hostages for ransom, steal cattle and provide “protection” services, including controlling smuggling routes.

Thompson said the two groups have worked together on at least five occasions but have had a falling out since as early as the summer of 2019. The Islamic State group has encouraged ISGS to be more aggressive in dealing with JNIM, which also has had defections to its rival. Security analyst Christian Nellemann said the two groups are battling to control mining sites.

“Islamic State propaganda has featured this conflict prominently, detailing attacks against JNIM cells and actively encouraging defections from JNIM to ISGS,” Thompson wrote. “The depth of the conflict suggests that, while some local cells may be able to reduce the level of intra-jihadist violence, the two groups are unlikely to restart collaboration in the manner observed in 2019.”

COVID-19 has made matters worse. The pandemic shut down ports and borders throughout Africa, which reduced money and supplies to both groups. That, in turn, pushed the extremists further into the gold market.

“The tri-border area between Burkina Faso, Mali, and Côte d’Ivoire is characterized by illicit smuggling and small arms trafficking that accompany goods being transported through Côte d’Ivoire to commercial hubs in Mali and Burkina Faso,” noted Daniel Eizenga and Wendy Williams in a December 2020 brief published by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies. “This area is also developing into a new hub of artisanal gold mining.” They reported that a string of attacks starting in 2020, “combined with prospects for gold exploitation, have heightened the risk of insecurity in this region.”

Mahamadou Sawadogo, a Burkinabe security analyst, said in June 2021 that extremists had spent the past year expanding their territory around Burkina Faso. “No matter which region, their first target is to control the mining area,” he told the Financial Times. “It’s their top revenue source, and also a good place for them to recruit young men.”

In a study, the International Crisis Group noted that artisanal gold mining is fueling violence and criminal networks. The group concluded that the only way to stop the extremists is to step up subregional and international security throughout the mining areas.

of Burkina Faso. THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

UNTENABLE SITUATION

Researchers noted that the current situation, in which artisanal sites are mining gold with either insufficient or nonexistent security protection, is untenable. The study recommended:

Artisanal gold mining must be preserved because of its “positive consequences,” which include providing jobs to citizens who might otherwise be forced to work with extremists. In some cases, gold miners are reformed extremists.

In gold-bearing areas marked by violence, governments should either deploy their security forces near the sites or formalize the role of local independent security groups. Such security need not necessarily be deployed at the actual gold mines.

In using independent security groups, governments will need to install supervisory mechanisms to prevent such groups from becoming “predatory elements.”

Governing groups need to strengthen subregional and international regulations and improve due diligence to better control gold production by limiting its capture by violent extremists.

Governments need to formalize the mining process by issuing gold mining permits and setting up authorized trading posts.

Officials should grant tax advantages or provide basic services to show artisanal miners that the government can help them.

Governments must find a balance between industrializing sites, generating taxable income and preserving artisanal mines so that workers continue to have jobs.

“Sahelian states should encourage the formalization of gold mining activities, while taking care not to alienate the gold miners,” the study noted. “They should redouble their efforts to secure gold mining sites and prevent security forces or allied militias from becoming predatory elements. The governments of these countries and those who buy their gold should strengthen their regulation of the sector.”