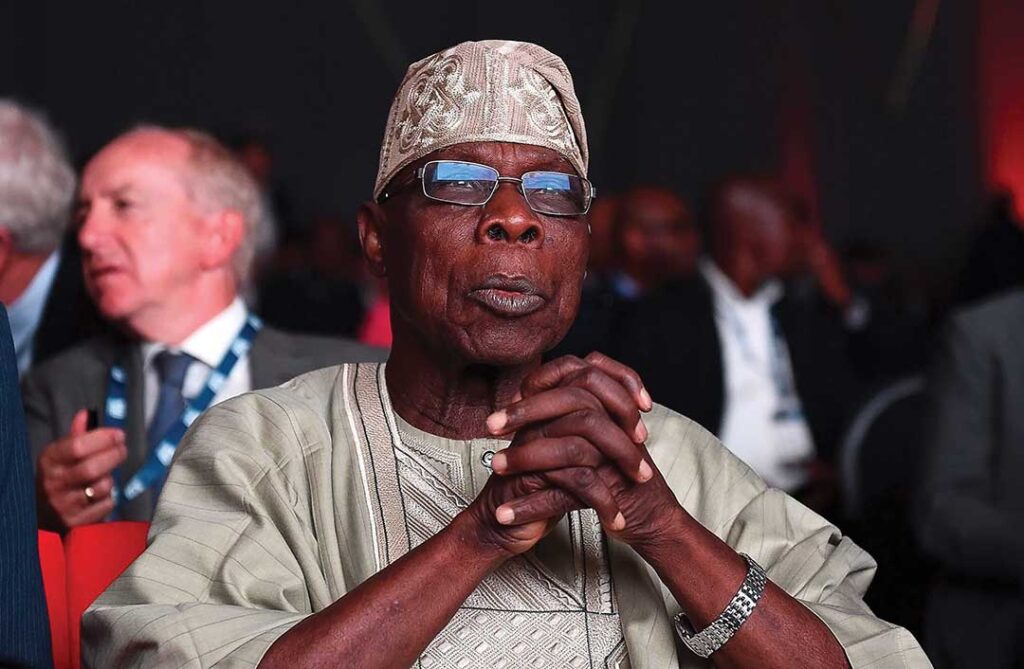

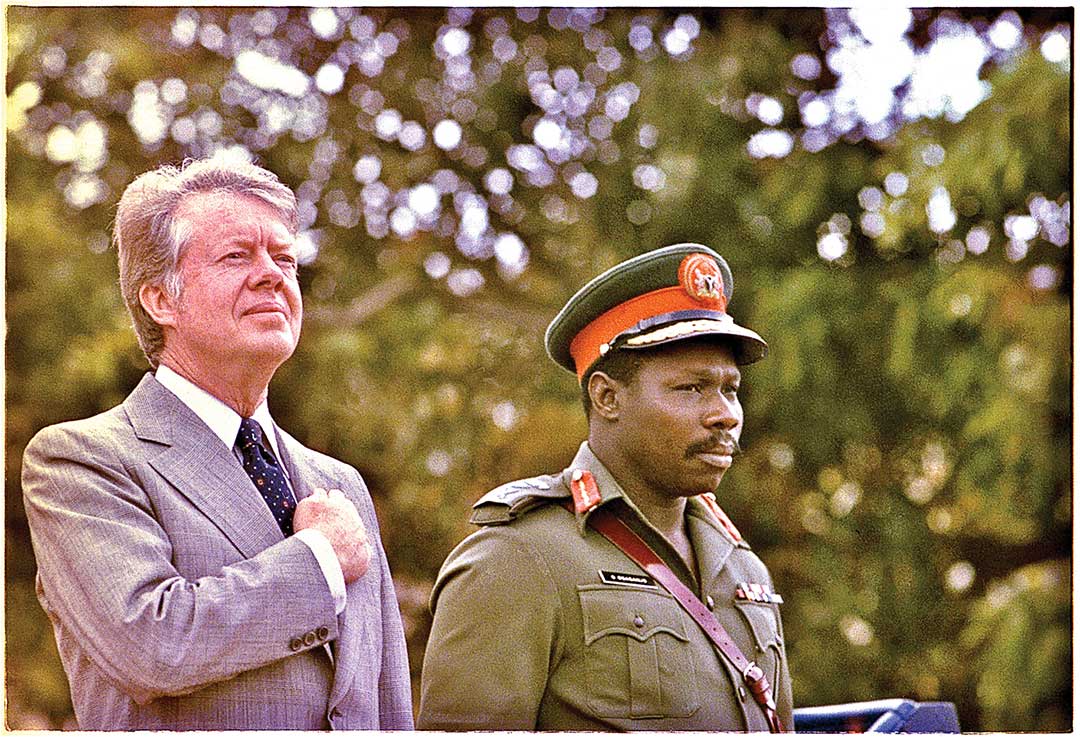

Affectionately called the “Baba of Africa” or “Africa’s father,” Olusegun Obasanjo has spent time as a military officer, statesman, peacemaker and human rights advocate. Born in 1937 in southwest Nigeria, he spent more than 20 years in the Armed Forces, rising to the rank of two-star general. He served as Nigeria’s head of state twice, from 1976 to 1979 and again from 1999 to 2007. In 1979, he became the first military ruler in Africa to hand power to a civilian government, and in 2007 he participated in Nigeria’s first peaceful transition of power from one civilian administration to another. After his presidency, he has served as a mediator in numerous conflicts and has headed election-monitoring efforts across the continent. In 2021, he was appointed African Union envoy to the Horn of Africa. He spoke to ADF by phone from his home in Abeokuta, Nigeria. His remarks have been edited to fit this format.

ADF: As a young man, why did you decide to serve your country in the Armed Forces?

Obasanjo: In my day, the opportunities for higher education in Nigeria were limited. In the mid-1950s when I was leaving secondary school, there was only one university in Nigeria. I was admitted to the University of Ibadan, but I had no sponsorship so I couldn’t go. Then the opportunity for furthering my education through the Army came when I saw an advertisement to become an officer cadet. It was necessity, excitement and the attraction of something new. I didn’t come from what you would call a military family. The tradition in my family was in the intertribal wars and that sort of thing. My family used to be distinguished in that. But nobody in my family had joined the Army before I joined. That’s what got me in. It was curiosity, excitement and necessity.

ADF: During more than 20 years of military service, was there an event that was most important? What stands out to you?

Obasanjo: I probably would give you two things. The first was my training in Accra, Ghana. I joined the Army before Nigeria’s independence, and in those days we had what they called officer cadet training school for British West Africa in Ghana. There I met Sierra Leonean students, Ghanaian officer cadets, Nigerian officer cadets from all parts of Nigeria –– Yoruba, Igbo, Northerner –– and that really was a very important experience in my life. It was very significant. I carried that for furthering my military training in the United Kingdom where there were not only African students, but students from the rest of the commonwealth. Very early in my life that was very instructive and a little bit determinant.

The other and more important event was when I had to go to serve as part of the United Nations Peacekeeping Operation in the Congo in 1960. That was graphic. The lessons I learned in those early days of my training and the early exposure to international service through peacekeeping as a very young officer remain indelible in my memory and in my life.

ADF: You have been a vocal opponent of military rule in Nigeria. In fact, in 1979 you became the first Nigerian military head of state to hand over power to a democratically elected civilian government. What drove you to push for civilian leadership?

Obasanjo: It was mainly influenced by my military training. In the training that I had, the military is subject to the civil authority. That was ingrained in my own training and life. When coups started in Africa soon after the period of independence, this was contrary to my training. It was contrary to the ethics of the military. The other thing that I saw was that it, in fact, undermined the organization of the military. The military is a hierarchical organization. When you find a man who yesterday was your junior now is taking the gun to the statehouse and he has got the prime minister or the president shot or arrested and he then becomes the military president, it disorganizes the hierarchy of the military. It offended the military camaraderie. I believe the best thing to do is put the military back to where it should be: in the barracks. I believe that we should get the military out of government and get them properly trained, properly professionalized, properly equipped. That’s what the military wants: to be ready for service in support of the civil authority.

ADF: You spent three years in prison from 1995 to 1998 for opposing the military rule of Sani Abacha. Why did you stand up for these democratic principles knowing that you could pay such a heavy price?

Obasanjo: If you believe in something, you must be ready to make a sacrifice for it. You cannot claim to be a believer in something and then not be ready to give what it takes. I believe that the military should not be in government, and I acted when I needed to act on it. I believe that if you don’t stand for something, you will fall for everything. In a life that is dedicated to principle, to certain standards and rules, you must be willing to pay what it takes. At the end of the day, you may be proved right, but if you are proved wrong, you must be ready also to accept that. Over the years I seem to have been proved right in this case.

ADF: Upon your release, you ran for office as a civilian and were elected president in 1999. You made military professionalism one of your top priorities as president, and after taking office, you forced the retirement of 93 military officers. Why was that important, and what signal did it send to the military and the country?

Obasanjo: We had this musical chairs of the military removing the civilians, then the civilians come back and the military removes them again, and so on. People were saying, “Look, what can we do to stop this cycle of coups?” Some people said, “We can put it in the constitution that a coup is treason.” The problem with that is the people who carry out coups know that it is treason. That’s why they don’t leave anything to chance. I thought that if you make it easy for people not to go into coup-making, by making sure that –– and it doesn’t matter how long it takes –– that for those who participate in coups or derive maximum benefit from coups it doesn’t pay. Then you make it easy for people not to want to go into coups. That is what made me retire those officers. It was not because they were otherwise bad, because later on we brought some of them back into the military, we appointed some of them as ambassadors, we even called in some of them to join political parties and so forth. Some became democratically elected governors. But coup-making was discouraged, and it remains discouraged up until today. The idea is when you have come as a military professional, remain professional. Dedicate your life to serving your country and your people and serving humanity that way. If at any time you choose to change your profession, you are free to do so. But don’t use the military and the gun that is given to protect your state to destroy your state. Don’t take over the running of your country at gunpoint.

ADF: How did you try to institute military professionalism in Nigeria during your time in office?

Obasanjo: Because of my own background in the barracks as a second lieutenant up to a two-star general, I know what a military officer wants. He wants to be well trained. He wants to be well equipped. He wants reasonable accommodations. When we had our civil war, the Nigerian Army grew overnight from about 12,000 to well over a quarter of a million. One of the greatest problems was accommodations, so I paid personal attention to this. We even bought prefabricated material so that we could build barracks. That was very important. Another thing was training. We paid attention to training both in Nigeria and out of Nigeria and set up the first staff college. We also went to the extent of setting up the National Institute for Policy and Strategic Studies, which is partly military, partly civilian. All these were a way of really strengthening professionalism. Another thing we introduced was financial. When I was a young officer, you could get a loan to buy a car. I brought that back so the young officers can buy their own car and over five years pay back the loan. Just to give them the normal, basic things that were there when I was growing up in the military. It had been disappearing as a result of the military participating in the civil war and growing to a number that was almost unmanageable. All that needed to be done to cater to the welfare and well-being of officers and men was for them to see themselves proudly as military people.

ADF: You have a long history as a mediator, playing that role in conflicts in Angola, Burundi, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mozambique, Namibia and South Africa. In 2008, you were appointed the U.N. secretary-general’s special envoy for the Great Lakes Region. What special skills and insights do you try to use to mediate conflicts?

Obasanjo: My upbringing is particularly useful in mediation. I grew up in a culture where mediation is regarded as part of our living and lived experience. We believe that wherever there are people, there will always be something to mediate, to reconcile, to appease and all that. A mediator must hear all sides and must be absolutely neutral. Not that you don’t have emotion as a human being, but your emotion must be subdued. You must also know the background of any issue you are trying to mediate. What is the history? What has gone on before? You must know what is the minimum that either side will accept. They will have a gap, and your job must be to gradually reduce that gap. If one says, “I will accept five” and the other is asking for 10, how do you get the one that says only “five,” to six and the one that says “10,” how do you get him or her to nine? You start narrowing. We believe that a mediator must have patience. Whatever happens, you are always taking it without being annoyed. People will say things against you, but you should stand for what is true. People don’t normally like to hear that. Each side wants to feel that they have won, and a good mediator will make each have a sense of winning.

ADF: Did your military career help?

Obasanjo: In the army you learn that at the end of almost any war or conflict, there’s always negotiation, mediation, discussion, reconciliation. In my own country we fought a civil war where we destroyed the longest bridge we had, the only refinery we had, we killed on both sides. It was a war that we should never have fought, but at the end of it we still had to reconcile. Mediation requires skill based on experience, skill that you get from the culture of the people. In our part of the world, we say that a mediator should be ready to get a bloody nose. A mediator must not take sides. In the military, of course, there are certain things you learn. For instance, how do you treat prisoners of war? These things that I have come to see in mediation are also essential. Every group should have a sense of something in it for them. There should be no victor, no vanquished.

ADF: Since leaving office, one of the roles you’ve played across the continent is election observer, most recently in Ethiopia. Why is monitoring elections so important to you?

Obasanjo: Monitoring an election gives, particularly the opposition, a feeling that all things will go well. It says that the group or party in power will not ride roughshod over all things. It helps for peace and credibility in elections.

Of course, there is no election that you can ever regard as totally perfect. No matter how large or how meticulous observer missions are, there will still be things that they will not be able to see. But there is a feeling within the country that observer missions are engaged, that, if things go wrong, these people will point them out. I always say to countries where I go for election-observation missions: “We are observers; we are not interventionists. We will report what we have seen, but we are not judges.” We also suggest and make recommendations on how things can improve. In some cases that has worked. Initially I did not want to go to Ethiopia. I was wondering, “What purpose will an election serve?” The chairperson of the AU, Ambassador Moussa Faki, called me, and I said, “I’m reluctant.” He said, “What purpose would you want the election in Ethiopia to serve?” I said, “I would want it to open the way for negotiation. Open the way for discussion between the Tigrayans and the central government and among the different groups in Ethiopia.” And Ambassador Faki said, “Well that is why you should accept this responsibility. If you are there, you may be able to encourage them to do this.” That is why I went and, to some extent, he was right. Although we are not where we should be in Ethiopia yet, I believe after the election everybody is more or less willing to talk. An election observer mission doesn’t solve all problems, but where it can be of service, let’s put it in place.

ADF: As Africa emerges from the COVID-19 pandemic, what is your greatest hope for this generation of security sector leaders and civilian leaders? How should they seize this moment? Do you have any advice?

Obasanjo: We have a number of things ahead of us, and there are tools to guide us. We have the United Nations Vision for Africa 2030; we have the Africa We Want 2063. We have the challenges that are there for all of us. We have the climate change challenge, the security challenges all over Africa, local terrorism, international terrorism, poor management of our economies, poor governance and, on top of all that, we have the COVID-19 pandemic. What will I say? Although things look bleak, if we get ourselves together nationally, regionally and continentally, I believe we will swim together rather than sink individually. What we need is not beyond us. We must realize that the world we live in will not give us everything on a platter of gold. We have to struggle. We have to let the world know that we are part of the world, and we will work hard to get what we need. We can do that together within our communities, together in our nation and together within the continent. There must be partnership within Africa, integration particularly on the economic front and partnership between Africa and the rest of the world. The youth must realize that nobody should tell them, “You are the leaders of tomorrow.” I would tell them this: “Your leadership begins today.” Otherwise, some people will destroy their tomorrow. They must be part of today, so their tomorrow is not destroyed.