Tanzanian Cpl. Ali Khamis Omary was serving in the United Nations peacekeeping mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, trying to halt the spread of Ebola. He and his colleagues had been sent to a camp in the eastern part of the country on a joint mission with peacekeepers from Malawi.

Rebels attacked Omary and other peacekeepers on November 14, 2018. He was shot in the leg, and Malawian Pvt. Chancy Chitete rushed to help him, administering lifesaving first aid.

Chitete dragged Omary to safety despite enemy fire, but he was shot and killed in the process.

Thanks to the actions of Chitete, described by United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres as “a true hero,” peacekeepers successfully forced rebels from their stronghold, enabling the U.N. to continue working to eradicate Ebola from the region. “He personally made a difference — a profound one,” Guterres said.

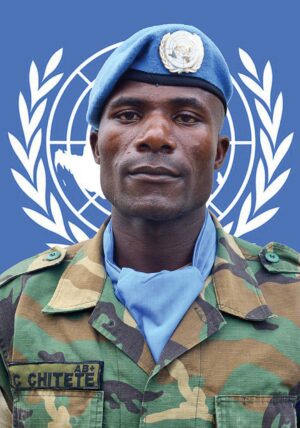

In May 2019, the U.N. honored Chitete at a ceremony in New York, where his family received the Captain Mbaye Diagne Medal for Exceptional Courage on his behalf. It is the U.N.’s highest peacekeeping honor.

There are many such examples of military professionalism, devotion to duty and courage under fire. There are stories of peacekeepers who refuse to abandon the people they have been tasked with protecting, leaders who refuse to participate in military coups, and Soldiers who put down their weapons only because they respect the leaders who have ordered them to do so.

These are Soldiers who know that their countries are best served by civilian, rather than military, rule. These are Soldiers who believe in democracy and the rule of law and know the value of human life.

DUTY TO PROTECT

Capt. Mbaye Diagne, whose name is on the U.N. award Chitete received, was such a man. In 1994, after the assassination of the president of Rwanda, soldiers of the presidential guard tortured and killed Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana, her husband and 10 Belgian peacekeepers. Hutu extremists took power and began carrying out a genocide, killing members of the Tutsi minority and some politically moderate Hutus.

U.N. peacekeeper Mbaye got word of the murders. The Senegalese captain went to investigate and found the prime minister’s five children hiding. Mbaye hid the children under blankets in his vehicle and drove them to the safety of a Kigali hotel, which served as a U.N. compound.

The genocide lasted 100 days, with more than 800,000 Rwandans slaughtered. Mbaye, working on his own, began rescuing people from the roaming killers, hiding them in his vehicle. As a U.N. observer, he always was unarmed.

The U.N. had rules forbidding its observers from rescuing civilians, but Mbaye knew that the circumstance demanded extraordinary measures. In his rescue missions, he could carry as many as five people under blankets in the back of his vehicle. He passed through dozens of checkpoints on each trip.

He never got caught. Two weeks before his scheduled return to Senegal, he was driving to U.N. headquarters when a mortar shell landed behind his jeep. Shrapnel hit him in the back of his head, killing him. He was 36 years old.

In 2014, the United Nations created the award in his honor. The U.N. considered 10 people for the award before deciding that the first one should go to Mbaye’s family.

On May 19, 2016, then-U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon presented Mbaye’s widow, Yacine Mar Diop, and their two children with the inaugural award.

Journalist Mark Doyle described Mbaye in simple terms. The big Senegalese Soldier was “the bravest man I have ever met.”

THE RELUCTANT CEASE-FIRE

In the war against apartheid in South Africa, Nelson Mandela was the movement’s face and its diplomat, while Chris Hani was its military general. Because of his intelligence and education, Hani was regarded as second only to Mandela in terms of popularity among the anti-apartheid forces. He was particularly admired for his insistence that women in the movement be treated as equals.

Hani orchestrated daily attacks on businesses and was responsible for the guerrilla warfare that eventually forced the South African government to the negotiating table. On August 7, 1990, after 14 hours of talks between the South African government and leaders of the African National Congress, Mandela announced that all attacks would cease immediately so that a new Constitution could be drawn up.

Hani believed the cease-fire was premature and faced the moral dilemma of either continuing the raids or obeying his unofficial commander in chief.

In undated video interviews after the cease-fire, Hani made no apologies for his wish to continue fighting.

“I didn’t sleep when our delegation was locked in negotiations, and when the decision came, I felt like crying,” he said. “I was deeply bitter that it had been taken without consultation with those of us who were involved in the physical side of the struggle. But as a disciplined Soldier I accepted it. When it was later explained to me that this was important to maintain the momentum of negotiations, I accepted to be reined in.”

The relative peace that came afterward would not have been possible without Hani’s cooperation. He was as crucial to the end of apartheid as was Mandela.

Hani was assassinated on April 10, 1993, outside his home. The two men convicted of the murder claimed to be acting on orders from the far-right Conservative Party.

STICKING TO THE CONSTITUTION

When Malawian President Bingu wa Mutharika died unexpectedly of cardiac arrest on April 5, 2012, political leaders decided to keep the death a secret while they looked for ways to block Vice President Joyce Banda from assuming the presidency.

Banda already was unpopular within the administration before the president’s death. Mutharika had delegated some of her duties to his first lady and wanted his brother to succeed him when he eventually left office. There was considerable resistance within the administration to the notion of a woman ever becoming president.

Banda’s opponents asked the military to step in and prevent her from taking office. Gen. Henry Odillo, commander of the Malawian Defence Force, refused, saying he was constitutionally bound to support Banda. He said that any other government would be illegal. He took the additional step of stationing troops around Banda’s house. After two days, Banda was sworn in as president.

“One cannot imagine what would have happened in Malawi if the Army had succumbed to the ill-advised offer to seize power,” Zambian Brig. Gen. Joyce Ng’wane Puta said, according to a report by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies (ACSS).

Two years later, in a dispute between Banda and her political opponents, word began to circulate that the military would seize power in a coup against her. Odillo quickly issued a statement in support of Banda and ordered his troops to remain in their barracks until the crisis was resolved.

Peter Mutharika defeated Banda in presidential elections in 2014. Odillo was quickly replaced as chief of staff. Since then, he has faced trial on charges of corruption, but his act to uphold the Constitution still is viewed as a shining example of military professionalism.

NO POLITICS WITHIN THE MILITARY

In 2015, longtime Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni’s ruling party, the National Resistance Movement, stood accused of trying to intimidate opposition leaders, including threats of violence. There were reports that some opposition leaders were forming their own militias to protect themselves.

One of the ruling party’s officials said that people who opposed the results of the upcoming 2016 presidential election would be shot.

Gen. Katumba Wamala, then commander of the Uganda People’s Defence Force, would not abide it. He announced that politics would not be tolerated within the ranks of his Soldiers. The ACSS said Wamala issued an order saying that “all army officers are cautioned not to dare engage in politics and anybody who breaks the law will be dealt with.”

He later said that his Soldiers’ duty was to preserve the peace and enable people to exercise their right to vote. Shooting civilians, he said, was not part of their mission. “There is nothing as important as peace,” he said.

Wamala’s reputation as a man of high principles and an intolerance for political meddling are believed to have calmed the political climate of that time, leading to a mostly peaceful post-election period.

THE GHANAIAN SAVIORS

During the Rwandan genocide in 1994, the Belgian government decided that the troops of the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda were in danger. Belgium told Canadian Gen. Roméo Dallaire, commander of the mission, that his troops risked attack by Rwandan fighters as well as the Interahamwe, a Hutu paramilitary organization that was the main perpetrator of the slaughter.

Dallaire instructed Ghanaian Gen. Henry Kwami Anyidoho, deputy force commander, to shut down the mission to avoid any confrontations with the two groups. Anyidoho objected, saying he was determined to keep all 454 Soldiers of the Ghanaian contingent in place, protecting as many Rwandans as possible.

“I hadn’t even sought permission from home when I told him that we would stay,” Anyidoho told Al-Jazeera in 2014. “We didn’t have an alternative. We couldn’t abandon these people.”

Dallaire estimates that by standing their ground, the Ghanaian peacekeepers helped save as many as 30,000 lives.

“Their country demonstrated the courage that so many others absolutely were unable to sustain in the face of such a horrible catastrophe,” Dallaire told Al-Jazeera. “Others ran while the Ghanaians stayed.”

“The backbone of the whole thing, my being able to stay and doing anything at all, was due to the Ghanaians and to Gen. Anyidoho staying there,” Dallaire added.