ADF STAFF

More than two years after the first COVID-19 case was reported in Angola, officials still are battling misinformation about a disease that has killed 1,900 people in the country.

Some people adhere to the notion that Angolans are immune to COVID-19 due to previous malaria outbreaks, or that drinking alcohol and eating garlic can keep the coronavirus away. None of this is true.

Joana Domingos, a mother of two in Luanda, was among those who thought the pandemic was an elaborate global plot to target the world’s poor. Now she regrets falling for misinformation.

“I was very confused and scared about the possibility that my children and I would die from COVID-19,” Domingos said on the World Health Organization’s (WHO) website. “I decided to stop working, ban my children from going back to school, and eliminate any chance of being exposed to the COVID-19 virus.”

Misinformation about COVID-19 began spreading as soon as the pandemic began, and its momentum has proven hard to stem.

By 2021, misinformation about COVID-19 reached “crisis proportions” worldwide, Carl Bergstrom, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Washington, and his colleague Jevin West wrote in a 2021 paper for the peer-reviewed journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“It poses a risk to international peace, interferes with democratic decision-making, endangers the well-being of the planet, and threatens public health,” Bergstrom and West wrote.

Bergstrom and other experts blame social media for promoting polarization, as well as amplifying misinformation, Science magazine reported.

“In a schoolyard people cluster around fights, and the same thing happens on Twitter,” Bergstrom told the magazine.

In response to misinformation, the WHO and Angola’s Ministry of Health created the COVID-19 Alliance Project in 2020. The initiative helps protect the population from misinformation, which is false information that is spread regardless of intent to mislead, and disinformation, which is the hostile spread of false information by a government or organized group.

The project established Factos Saúde, a platform that tracks rumors and supports education about health and well-being. The platform has produced and disseminated 150 “debunking materials” that are widely shared on Facebook and WhatsApp, according to the WHO.

The initiative against COVID-19 misinformation has helped dispel rumors while lending credence to the health officials battling the pandemic, said Dr. Djamila Cabral, WHO representative in Angola.

“This initiative also makes it possible to identify the issues, doubts and concerns of the population that need specific action to be resolved,” Cabral said on the WHO website. “All of us have a responsibility to ensure that our populations are properly educated and protected from false and unsubstantiated health information.”

There are plans to expand Factos Saúde to Twitter and Instagram and create a WhatsApp hotline.

Domingos, the mother of two, wishes the platform had been around sooner.

“I think that if I had had access to Factos Saúde at that time, I would not have taken hasty decisions, nor suffered from fear of the measures recommended by the health authorities,” she said.

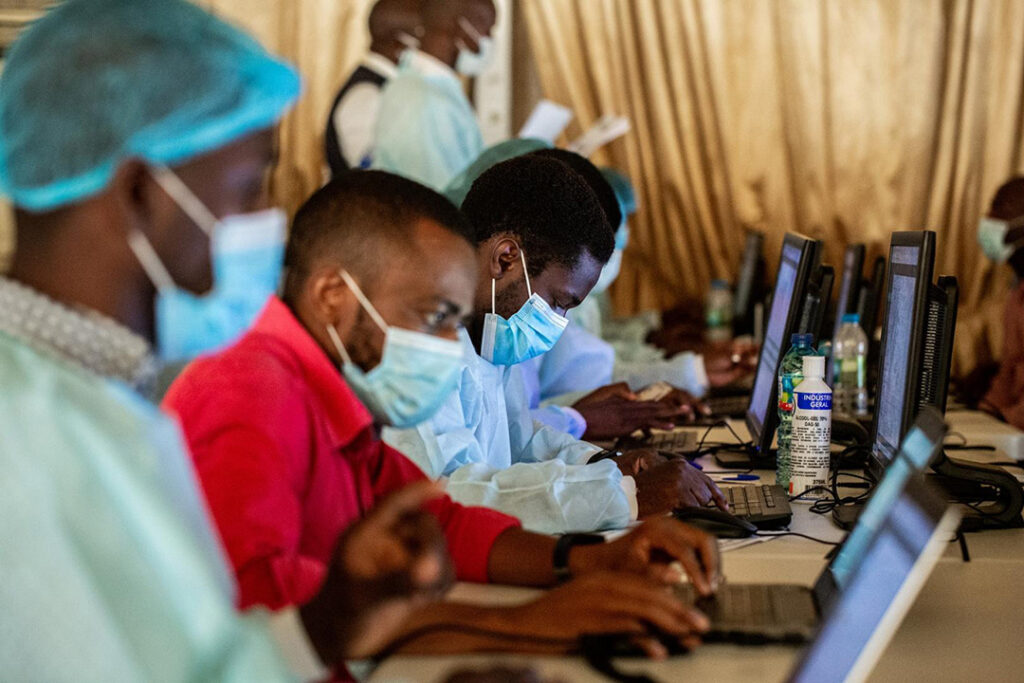

With help from the Alliance for Infodemic Management, the WHO also has supported training for Angola’s Ministry of Health to combat false information. Also, the Ministry of Health plans to create its own Rumor Management Laboratory that can monitor, track and debunk health-related rumors.