ADF STAFF

As the violent extremist threat festering in Mali began to spread into Niger and Burkina Faso, coastal states such as Benin became the next frontier.

On May 1, 2019, violence reared its head in that frontier, as assailants kidnapped two French tourists and killed their wildlife guide in Benin’s Pendjari National Park. French forces operating out of Burkina Faso later rescued the two tourists and two other civilians — an American and a South Korean — in an operation that resulted in the deaths of two French Soldiers.

On February 10, 2020, men armed with machetes and rifles attacked a police station in the Beninese village of Mekrou-Djimdjim near the border with Burkina Faso, killing one officer and wounding another.

What analysts have feared appeared to be coming true: Violent extremism was continuing its march out of the Sahel and into bordering coastal nations. Dr. Daniel Eizenga, a research fellow at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies (ACSS), told ADF in 2019 that Sahel extremists seek to “expand the battlefield.” Neighboring coastal states are ripe for that expansion and give terrorist groups opportunities to financially exploit commercial routes, such as those through which cattle are moved to markets.

The expansion also gives militants access to “large-scale attacks on soft targets,” such as the March 2016 Grand Bassam beach resort attack in Côte d’Ivoire that killed 16 people, Eizenga said.

As these attacks were taking place, Benin’s government was directing its attention to internal political matters. Observers say that President Patrice Talon, elected in 2016, soon began to weaken his political opponents and the nation’s reputation as a strong, established democracy.

Upon taking office, Talon vowed not to seek reelection, but as his term neared its end, he changed his mind. Along the way, he “eliminated almost all possibility of legitimate opposition,” wrote Tim Hirschel-Burns in April for Foreign Policy. Talon’s personal lawyer became head of the nation’s Constitutional Court, and a judicial body formed to fight corruption and terrorism turned its sights to the president’s political rivals instead.

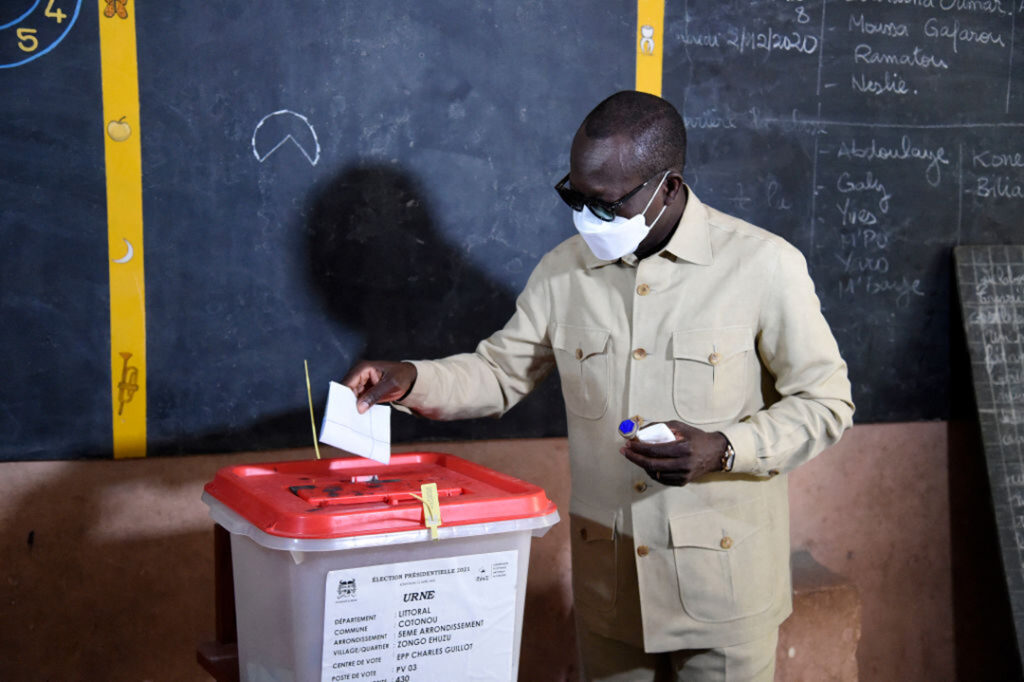

The result, wrote Dr. Mark Duerksen of ACSS in the April 27, 2021, paper, “The Dismantling of Benin’s Democracy,” was Talon’s April 11 reelection, in which only 26% of voters cast ballots. Although 16 African Union observers and 105 from Economic Community of West African States praised the calm and orderly vote, the result reflected a boycott after serious opposition was barred.

Weakening justice institutions till the ground for extremists to take root as they appeal to disaffected and neglected citizens, especially those in regions such as northern Benin that are far from government epicenters. The formula has been instrumental in turning the Sahel into a hotbed of continued extremist violence and unrest, wrote Dr. Catherine Lena Kelly, an associate professor with ACSS.

“It’s a potent message,” Kelly wrote in the May 25 paper, “Justice and Rule of Law Key to African Security.” “Human rights abuses by security sector actors and perceptions of unjust treatment by government officials are key determinants of individuals’ decisions to join violent extremist groups in the Sahel, the Lake Chad Basin, and the Horn of Africa.”

At a crucial time when Benin should be strengthening and extending the reach of democratic institutions, it instead has continued its march toward autocratic rule.

Benin has tried to play an active role in the fight against regional extremism. It participates in the Multinational Joint Task Force along with Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria against Boko Haram. It also has formed a domestic group called the High Level Committee for the Fight Against Terrorism and Insecurity at Borders (CLTIF). But even the CLTIF has been used to target Talon’s political opponents, wrote academic researcher Christina Cottiero for The Washington Post in May.

Extremists are likely to target Benin’s disadvantaged areas to exploit anger at ineffective governance. The north of the country, for example, receives fewer government resources than does the coast. “In neighboring Burkina Faso, groups such as Ansaroul Islam exploit feelings of injustice and resentment toward the government to radicalize people,” Cottiero wrote.

As extremists continue to expand the battlefield, violence in northern Benin is likely to continue. Cross-border crime also is a continuing problem, and extremists can be expected to exploit commerce there. Engaging with local populations and preserving democratic institutions will be key elements in combating the spread of violent extremism, observers say.

“Democracy is not only a governance vehicle for freedom, equality, and human rights, but it is also a means of advancing national security — domestically and internationally,” the ACSS’ Duerksen wrote.