ADF STAFF

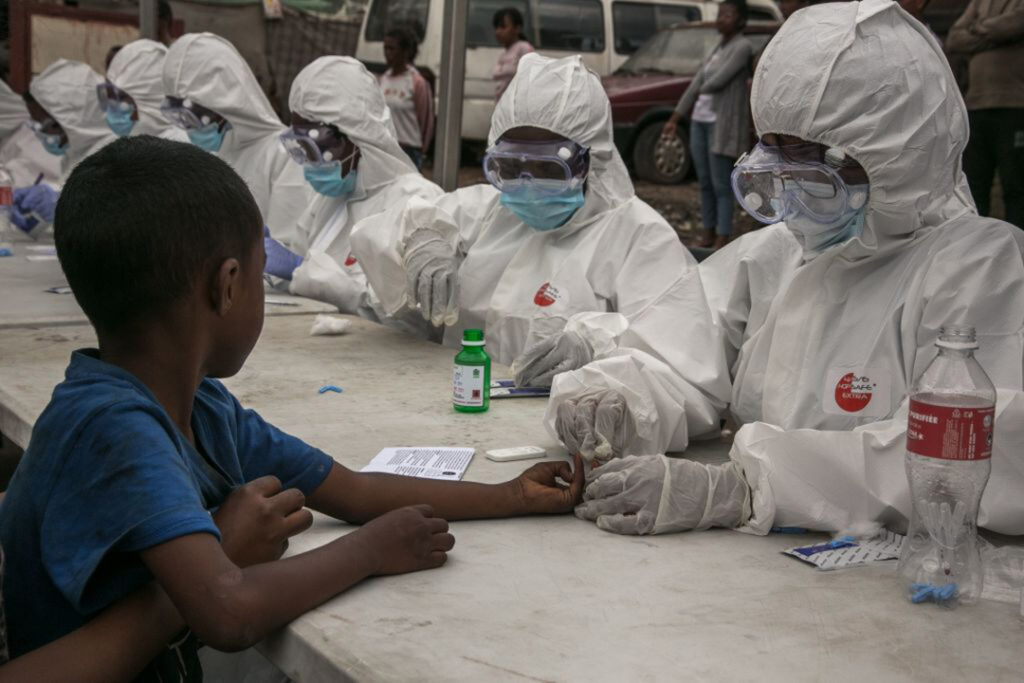

More than a year into the COVID-19 pandemic, the actual scope of infections among African nations might be larger than official records indicate.

A study led by Gambian medical researcher Dr. Effua Usuf in July 2020 that recently was published in the British medical journal The Lancet found 92 unrecognized COVID-19 cases for every one confirmed by a lab test.

About 2% of people testing positive realized they were carrying the virus. Of those with antibodies, about 8% did not know they had been infected because they had never been tested, according to Usuf.

Usuf conducted her study in Zambia. Previous studies looking at blood antibodies in Mozambique and Kenya found them in about 5% of the population — representing significantly greater transmission than official case numbers.

Official figures of the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) put the total number of cases on the continent at near 4.3 million as of early April 2021 with about 114,000 deaths. In his weekly update on April 1, Director John Nkengasong has noted that, since the beginning the year, Africa’s case fatality rate of 2.7% exceeds the global average of 2.3%, meaning the continent is seeing a growing death toll from the pandemic compared to other regions.

Beyond undiscovered transmission, African nations also struggle to provide an accurate number of deaths from COVID-19. Only eight countries track deaths in a way that meets international standards, resulting in a large gap between the reported number of COVID-19 deaths and the actual impact.

A study in Khartoum, Sudan, for example, determined that more than 16,000 people had died of COVID-19 there between April and September 2020, a period when official records put the death count at fewer than 500.

Usuf recommends combining blood tests with excess death estimates to get a true picture of COVID-19’s presence on the continent.

Official tallies of the pandemic’s toll on Africa have been much less than initially feared. Possible explanations ranged from the continent’s overall youth, to the rapid response to the first wave, to its large rural population.

Usuf’s research suggests that Africans have not avoided as much damage from COVID-19 as it might seem. Rather, there may be widespread transmission of the virus by people who have been exposed but never developed symptoms.

“Discrepancies between official numbers and infections measured by the survey can also be explained by this high prevalence of asymptomatic infections, since most testing strategies focus on patients who are symptomatic,” she writes in The Lancet.

As a result, Zambians drifted away from preventive measures such as masks, hand-washing and social distancing because they felt the virus posed less risk to them, Usuf wrote.

That’s a major concern as countries try to stop the variants driving infections across the continent. The B.1.351 and B.1.1.7 variants (also known as N501Y.V2 and N501Y.V1) are more transmissible that the original virus. As of early April, 36 of 54 African countries reported at least one variant. Some have both.

Vaccines still are effective against the variants. They significantly reduce symptoms, hospitalizations and deaths. But researchers worry that the continued spread of COVID-19 will lead to more variants that could be harder to control.

Nkengasong reported on April 1 that Angolan authorities had discovered a highly mutated variant in a traveler from Tanzania, where the government only recently began acting against the virus. It’s unclear whether vaccines will neutralize that variant, Nkengasong said.

Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, World Health Organization (WHO) director-general, continues to urge increased distribution of vaccines across Africa to slow the virus’s progress.

“The clock is still ticking on vaccine equity,” he said at WHO’s April 1 COVID-19 update.

The Africa CDC urges countries to keep close, systematic track of the virus within their borders to be aware of changes and potentially dangerous variants.

Without close surveillance, undiagnosed spread raises the risk of new variants getting a foothold before health authorities can catch them, according to epidemiologist Richard Lessells of South Africa’s KwaZulu-Natal Research and Innovation Sequencing Platform.

“If you allow it to continue to spread, it will continue to evolve,” Lessells told Scientific American.