ADF STAFF

As virologists race to decode COVID-19, its origins and early spread remain a mystery.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recently concluded a three-week advance mission in China that laid groundwork for a broader team of international experts to investigate how the virus that causes COVID-19 jumped from animals to humans.

“Epidemiological studies will begin in Wuhan to identify the potential source of infection of the early cases,” said WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus in remarks to the media on August 3. He did not specify when the investigation will take place.

The advance team was composed of two animal health and epidemiology specialists.

“The team had extensive discussions with Chinese counterparts and received updates on epidemiological studies, biologic and genetic analysis, and animal health research,” including video discussions with Wuhan virologists, WHO spokesman Christian Lindmeier told reporters.

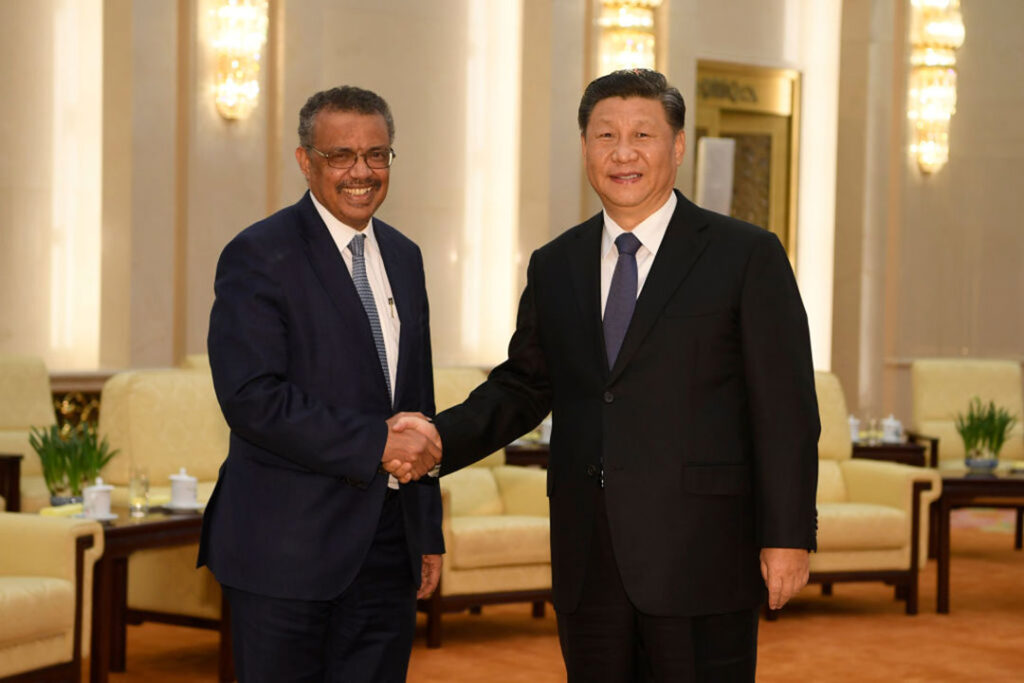

China acquiesced to pressure from more than 120 WHO member nations demanding an independent investigation during the World Health Assembly on May 18. In his remarks that day, Chinese President Xi Jinping insisted China acted with “openness, transparency and responsibility” when the virus was discovered in Wuhan.

That runs counter to a timeline the WHO published on its website.

Liu Xiaoming, China’s ambassador to the United Kingdom, told the BBC that Chinese health authorities notified the WHO on December 31 of cases of “viral pneumonia.” But the WHO said it discovered reports of the outbreak on the internet and sought answers from China the next day. China responded two days later on January 3.

Again, critical information appeared on the internet when a Chinese lab published the genome on January 11, which then prompted Chinese government labs to release it. China then delayed providing the WHO with data on patients and cases for at least two weeks, according to recordings of internal WHO meetings obtained as part of an Associated Press (AP) investigation.

“We’re going on very minimal information,” epidemiologist Maria Van Kerkhove said in a WHO internal meeting. “It’s clearly not enough for you to do proper planning.”

Health authorities in Wuhan and Beijing tried to minimize the story, first insisting the virus was not transmitted by humans and later claiming the risk was low. Weeks after the first cases appeared, China on January 20 confirmed that COVID-19 was contagious. Ten days later, still struggling to confirm basic medical information, the WHO declared a global emergency.

“Between the day the full genome was first decoded by a government lab on January 2 and the day WHO declared a global emergency on January 30, the outbreak spread by a factor of 100 to 200 times, according to retrospective infection data from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention,” AP reported.

As of August 19, there have been 22,239,071 people infected with COVID-19, and 783,333 have died, according to Johns Hopkins University’s COVID-19 tracker.

“It’s obvious that we could have saved more lives and avoided many, many deaths if China and the WHO had acted faster,” Ali Mokdad, professor at the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, told AP.

Much more damaging to any efforts to contain the outbreak was China’s withholding of data and information from the WHO, preventing other countries from recognizing the virus’s spread and developing tests, treatments and vaccines.

Profound changes must be made to global epidemic response, according to Dr. Ali Khan, formerly of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“We can’t afford to do this again,” he told BBC One’s Panorama program. “If … some countries having an outbreak [are] deciding to not share that information, there have to be consequences.”