ADF STAFF

Countries around the world are beginning to open shuttered economies as the COVID-19 outbreak continues. Many leaders want answers about the cause of the outbreak. Some have demanded compensation or debt forgiveness from China for the global harm the virus has wrought.

In Africa, some are calling for solidarity in the face of the crisis and saying that it should start with sharing the economic burden of rebuilding.

“It’s just an apocalyptic moment, and I don’t think we seem to be taking it as seriously as we should,” Ghanaian Finance Minister Ken Ofori-Atta said in an interview with the Center for Global Development. “Given the way the world came together following the Second World War, I think we are facing something like that.”

China experts believe major concessions relating to debt forgiveness are not likely to happen.

“The Chinese attitude towards that, to begin with, is quite resistant,” Yun Sun, director of the China program at the Stimson Center, a policy research center, told Voice of America. “It doesn’t mean that China will not engage in, for example, debt renegotiation or debt restructuring or even postponement to owe for a longer grace period for the African countries to pay back their debt. But I think a blanket debt forgiveness is not in the cards.”

International organizations may be unable or unwilling to put economic pressure on China, but African countries do have some options. This is particularly true relating to the One Belt, One Road (OBOR) project, which finances roads, railways and ports to expand trade. OBOR loans to Africa totaled about $146 billion between 2000 and 2017.

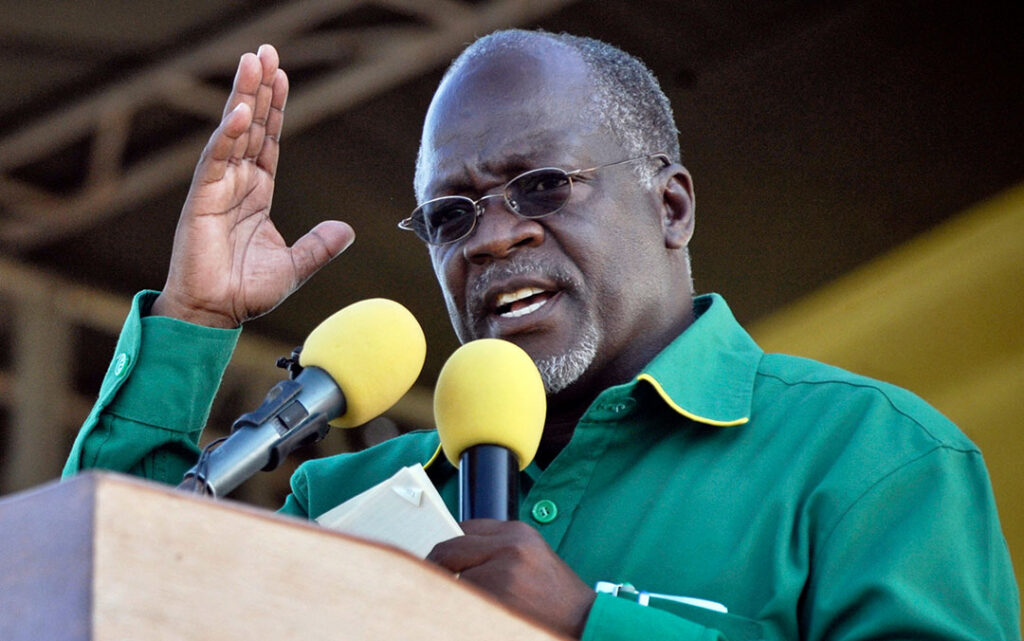

Tanzanian President John Magufuli recently announced that he is canceling a $10 billion Chinese loan to build a port in Bagamoyo. His predecessor, Jakaya Kikwete, signed the loan. In a widely published statement, Magufuli characterized the terms and conditions of the loan as so ridiculous that “only a drunkard” would accept them.

Nigeria’s House of Representatives has demanded a review or cancellation of the latest China loans on the principle of “force majeure” — unforeseeable circumstances that prevent a contract from being fulfilled. Because the National Assembly was not clear on how most of the loans were taken and used, the lawmakers want an investigative committee to scrutinize all Chinese loans dating back to 2000.

Other observers have weighed various strategies for putting pressure on China to negotiate with debtor nations. These include closing Chinese culture centers known as Confucius Institutes, threatening to resume diplomatic relations with Taiwan, or expelling Chinese workers.

To date, African nations have maintained hope that China will come to the negotiating table.

“This is another imposition from outside that is exacerbating the position we are in,” Ofori-Atta of Ghana said. “My feeling is that China has to come on stronger. Our African debt to China is $145 billion or so, $8 billion in payments this year and about $3 billion of that is interest. That needs to be looked at.”

China is considering several responses to calls for debt relief, including the suspension of interest payments on loans from the country’s financial institutions, Financial Times reported.

“We understand a lot of countries are looking to renegotiate loan terms,” said a researcher at the China Development Bank, a Chinese “policy bank” that helps spearhead hundreds of billions of dollars in lending to OBOR projects around the globe. “But it takes time to strike a new deal, and we cannot even travel abroad right now,” said the researcher, who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “The loans are not foreign aid. We need to at least recoup principal and a moderate interest.”

In April, the Group of 20 (G20) major economies, including China, agreed to suspend payment obligations on bilateral debt — a loan agreement between a single borrower and a single lender — owed by the world’s 77 poorest nations through the end of the year. The goal was to free up more than $20 billion that poor governments could use to bolster their health systems.

Kenya declined the offer because terms of the deal were too restrictive, Finance Minister Ukur Yatani said in a Reuters interview. Kenya is instead negotiating with creditor countries, including China, to secure moratoriums on debt service payments for about a year.

“The G20 debt relief initiative does not offer optimal benefit given the structure of Kenya’s debt portfolio,” Yatani said. “Every country adapts to the situation based on its own circumstances.”