Recurring Weather Events Can Intensify Security Issues

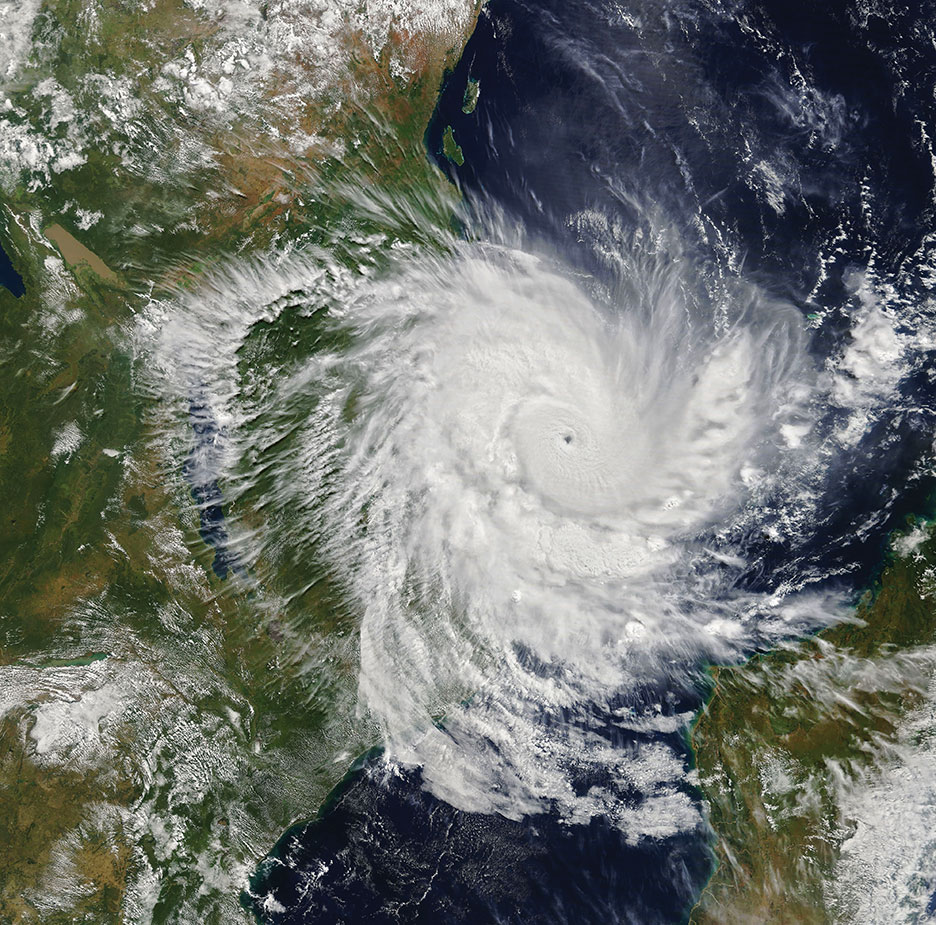

On a continent prone to a wide range of environmental disasters, tropical Cyclone Idai stood out. The exceptionally devastating storm plowed into southeastern Africa on March 15, 2019, bringing fury to Mozambique, as well as neighbors Malawi and Zimbabwe.

The storm might be the worst disaster to strike the Southern Hemisphere, the United Nations said. A month later, Mercy Corps reported that the cyclone had left an estimated 3 million people needing humanitarian assistance and killed more than 1,000, with hundreds more missing.

By April 25, 2019, Cyclone Kenneth was slamming into Mozambican shores, this time in the nation’s northeast. Idai hit as the nation was about to begin its harvest season. Kenneth brought heavy rain and flooding to Pemba, a city of 200,000, in the nation’s Cabo Delgado province. The storm had killed five people and flattened homes by April 28. Rain drenched an area prone to landslides and floods, leaving residents fearful that rivers would swell and cover large areas with water, according to the United Kingdom’s The Guardian. The province has been the site of deadly militant attacks for some time.

Two storms in less than two months in one of the world’s poorest countries. One storm complicating the nation’s farming industry. The other slamming into a region already home to insurgent violence. The results of both — and events like them elsewhere in Africa — can exacerbate existing tensions and cripple already-fragile states.

A VARIETY OF THREATS

Catastrophic weather and environmental events are common all over the continent, and not all are deadly cyclones.

For example, in Sierra Leone in August 2017, heavy rains caused mud to cleave off Sugar Loaf mountain and slide down on hundreds of people’s homes in Freetown as they slept. “We were inside. We heard the mudslide approaching,” a woman named Adama told the BBC. “We were trying to flee. I attempted to grab my baby, but the mud was too fast. She was covered, alive. I have not seen my husband, Alhaji. My baby was just 7 weeks old.”

A famine associated with an East African drought from 2010 to 2012 killed almost 260,000 — half of whom were young children — in Somalia alone, according to a United Nations report. Drought and famine are common in this region. Deadly famines in neighboring Ethiopia date back at least a thousand years.

Environmental hazards such as these, as well as floods, wildfires and other events, can interrupt a population’s ability to support itself through subsistence farming and prompt the mass migration of people from one area to another. These types of disruptions can stress populations and resources and bring about conflict or exacerbate existing tensions.

Governments and security forces can’t stop weather events, but they can be aware of environmental trends and how those trends are likely to affect certain areas and populations.

Studies show that climatic events do not cause conflict but can trigger or accelerate them.

Governments and security forces, knowing where conflicts have emerged during specific times, can expect them again when similar conditions arise. For example, pastoralists in a particular region may be inclined to migrate into farming territory in search of water for livestock during dry conditions.

THE LAKE CHAD BASIN

The Environmental and Energy Study Institute, a U.S. nonprofit committed to promoting sustainable societies, lists two major international threats from sustained environmental changes: mass migration leading to refugees and internally displaced people, and conflicts centered on water resources.

When a major environmental event occurs, it could cause thousands of people to flee to another area or even across a border into another country. One of the clearest examples of this in Africa is among the Lake Chad basin nations of Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria. Lake Chad itself has shrunk about 90 percent in the past 50 years. The lake historically has been a lifeline for the region through agriculture, fishing and raising livestock.

“This massive reduction of the lake has resulted in less water availability, decreased agricultural outputs for surrounding communities, and an increase in livestock and fisheries mortality,” wrote Abdoul Salam Bello for the Atlantic Council. “Moreover, as the human population that depends on the lake’s ecosystem for survival surges in size, the challenge of decreasing freshwater availability grows more and more acute.”

The importance of the lake to the region cannot be overstated. About 700,000 people lived around Lake Chad in 1976, but that number has grown to 2.2 million now as people have been drawn there by drought and poor living conditions elsewhere, according to a report from adelphi, a think tank that focuses on climate, environment and development. The number of people is expected to be 3 million by 2025, with 49 million depending on lake resources.

Before Islamist insurgent group Boko Haram became a security threat to the region, the Lake Chad basin thrived with trade across national borders in produce, fish and other goods. This occurred despite a lack of government support.

Understanding how the environment affects security requires a look at how it interacts with different risk factors such as the economy and social and political stressors. The adelphi study mentions three climate-fragility risks:

Conflict and fragility increase vulnerability: The ongoing Boko Haram conflict undermines resilience, including the population’s ability to adapt to environmental changes.

Natural resources conflicts: The environment can intensify natural resource conflicts, especially disputes over land and water use by herders and farmers.

Livelihood insecurity and recruitment into armed groups: When a large percentage of a population, particularly young people, cannot find employment, they may be more susceptible to recruitment by an extremist group or armed militia.

These fragility risks, taken together, can create a self-enforcing feedback loop between increasing livelihood insecurity, vulnerability to environmental changes, and conflict and fragility. Conflict makes communities more vulnerable to environmental changes, which in turn aggravates competition for scarcer natural resources. “If not broken, this vicious circle threatens to perpetuate the current crisis and take the region further down the path of conflict and fragility,” the study shows.