The Values of the Next Generation of African Security Sector Leaders

By Dr. Kwesi Aning and Dr. Joseph Siegle

The role of African security sector professionals has changed greatly in recent decades. Leaders today face a dizzying array of challenges from armed militias, violent extremist organizations, terrorism, piracy, insurgency and instability caused by political crises, to name a few. These threats span domestic, regional and transnational theaters — sometimes simultaneously. Contemporary African security sector professionals, consequently, are required to be enormously versatile.

Although considerable attention is given to Africa’s security challenges, relatively less reflection has been paid to the security sector actors themselves and how they are adapting to the rapidly changing security environment.

To gain some insight into this issue, the Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre and the Africa Center for Strategic Studies conducted an anonymous digital survey of 742 current and retired African security sector professionals from 37 countries in April 2017. The survey assessed their attitudes across a variety of issues involving motivations, values, formative experiences and threats faced. Respondents represented the military, police and gendarmerie, ranging in rank from sergeant to general officer. With an aim of discerning differences in perspectives across generations, this research compared results among respondents from four equally divided age cohorts spanning ages 25 to 70. These results were supplemented with 35 face-to-face interviews to provide qualitative insights into the topics of interest.

Education

The survey results showed that the youngest security sector professionals were starting their service with considerably higher levels of education compared to their older counterparts. Of the respondents in the oldest cohort, 47 percent had a high school education or less when they joined, compared with 26 percent for the youngest group. Conversely, 41 percent of the youngest quartile entered service with a bachelor’s degree, compared with 30 percent of the oldest cohort.

The military demonstrated the largest gains in education levels of its service members. Fifty-six percent of the youngest cohort of military respondents began service with a bachelor’s degree, compared with 26 percent for the oldest age group — a 30 percentage point gain over several decades. Police recruits possessed the lowest educational levels among the services with a third starting with a bachelor’s degree — roughly the same as those with a high school education.

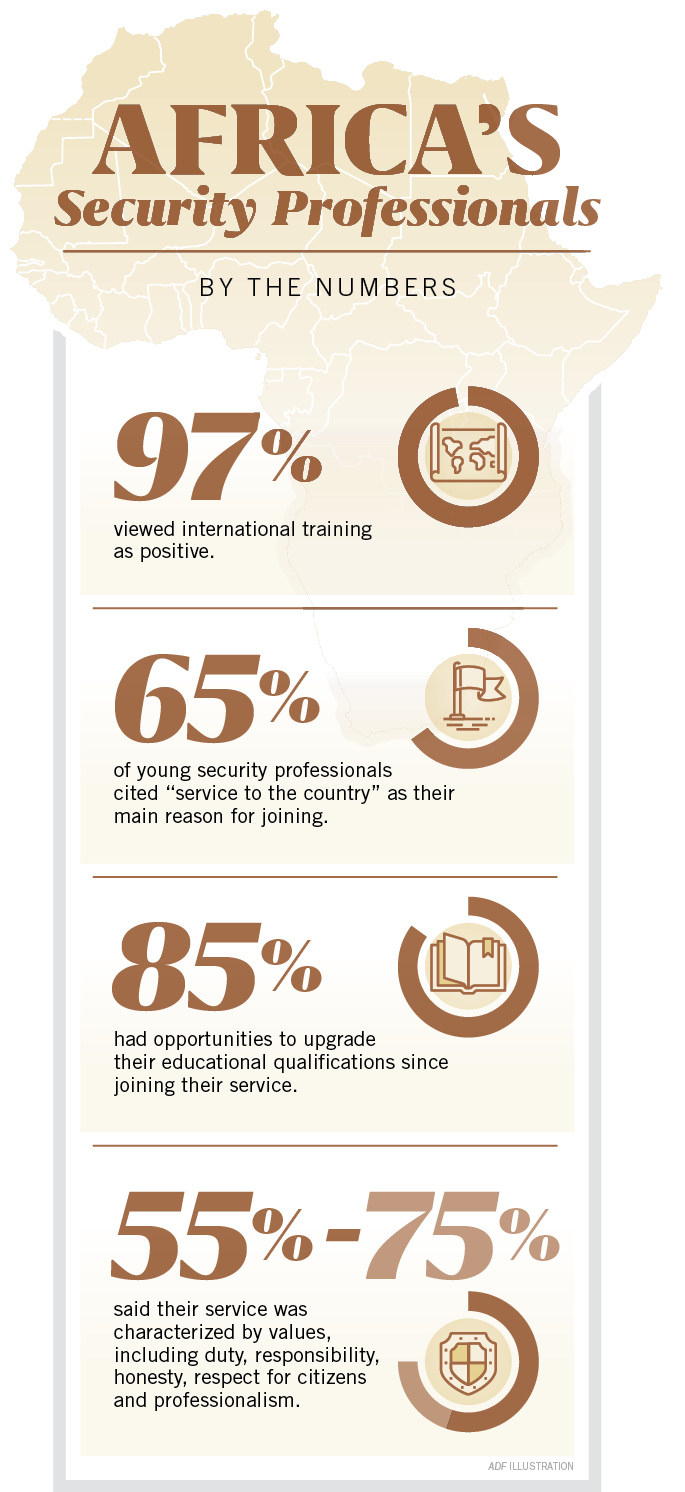

Reflecting a growing commitment on the part of African security services to professional development, 85 percent of respondents indicated that they had had opportunities to upgrade their educational qualifications since joining the service. This included opportunities to earn vocational or technical certificates and bachelor’s and master’s degrees.

Motivations

People enter a career in security for a wide variety of reasons: patriotism, a drive to protect others, as a family tradition or as a means to professional and economic advancement. Usually, the answer is a mixture of many reasons.

In response to the survey questions, significant generational differences emerged in motivations for joining the service. The youngest cohort led all age groups in citing “service to the country” as their primary motivation. Sixty-five percent of this age group gave this reason, compared to 57 percent for the oldest cohort. Older service members, conversely, were much more likely to join because a family member had been in the service.

The combination of higher education levels, motivation to serve the public, and fewer familial ties to the service suggests that there has been a shift in reasons for joining the security sector. Young service members appear to have more skills and employment options, yet are choosing to join the security sector as a career. This trend offers prospects of an increasingly capable force with potentially higher standards of professionalism, civilian control of the security sector and state-society relations.

Values

Important institutional differences also were observed in the area of values. Strong majorities of military respondents, at rates of 55 to 75 percent, indicated that values such as duty, responsibility, honesty, respect for citizens and professionalism characterized their services. By contrast, only a minority of respondents from the police or gendarmerie, ranging from 38 to 44 percent, claimed these values reflected their institutions.

Two values, “service to the public” and “merit-based,” did not resonate strongly across all services. A minority of respondents in the military (48 percent), gendarmerie (38 percent) and police (25 percent) felt these values characterized their institutions. These deviations raise important questions over the perceived purpose and fairness of security institutions.

There is, moreover, a strong age component to the value identification process. Younger people were consistently less likely to identify with these values than were older generations. Only 32 percent of the youngest cohort, for example, identified with the value of “service to the public.” This is particularly noteworthy since this group had indicated that desire to “serve the country” was the strongest factor in their recruitment.

Strong divergences on values also were seen by gender. Female respondents ascribed any of these values to their institutions at rates of only 25 to 45 percent. These age and gender differences may reflect an erosion of the institutional ethos among younger service members and women. Alternately, they may reveal a greater willingness for constructive self-criticism by the younger generations and female service members as they seek to reform areas of perceived deficiency in their institutions.

Regime Type Affects Perceptions

The survey also revealed notable differences in perceptions of risk depending on regime type. Specifically, security professionals with autocratic governments were four times more likely to list civil unrest, political crises or violent extremist organizations as serious threats compared to those with democratic governments. For example, just 11 percent of respondents from democracies saw political crises as a serious security threat in their countries. By contrast, 41 percent of those from autocracies felt there was a serious security risk stemming from a political crisis.

Training and Identity Formation

One of the strongest findings from this research was the resounding importance attributed to international training. Some 97 percent of respondents viewed international training as positive. Moreover, respondents identified international training as the most important formative experience in shaping the identity of their service. This view was particularly strong among the three oldest age quartiles. For the youngest cohort, domestic training was cited as the most influential factor, followed by international training.

Military respondents stood out, by a 2-to-1 ratio, in affirming the importance of international training relative to domestic training as an influential experience in shaping their service. This pattern does not hold for the police and gendarmerie, however, who rate domestic and international trainings as equally influential.

The value of international training as a formative experience was strongly validated in interviews. Service members cited the broadening intellectual and professional experience, exposure to peers from other countries facing similar challenges, the strengthening of regional security perspectives, the building of lasting relationships, and exposure to different technologies as some of the compelling benefits they gained from these experiences.

Notably, peacekeeping also was highly rated as a formative experience. Despite the domestic orientation of police, peacekeeping was reported to be their single greatest influence. This may reflect the growing frequency of deployments by police in peace operations — and the influence of these experiences on self-identity and professionalism. For the gendarmerie, peacekeeping experiences ranked on par with domestic and international training. For military respondents, it was second, after international training.

Implications

The findings of this research describe an African security sector that is increasingly well-educated, committed to serve and eager to strengthen its capacity. Moreover, 92 percent of those surveyed indicated that their expectations are being met. This suggests an overall positive story for Africa’s security forces. This apparently has been greatly aided by a commitment by African governments to support educational advancement for their service members. This is creating an increasingly well-educated security force, with the partial exception of the police, whose members have been lagging behind the military and gendarmeries in their starting levels of education and subsequent advancement.

Continued support for capacity-building opportunities through education, domestic training and international training is important for maintaining this positive trend. Given the far-reaching demand and benefits from international training, there is value in the continued strengthening of professional military education institutions on the continent.

The age and gender differences regarding perceived institutional values provide a potentially important entry point for reform as part of an institution-strengthening agenda. Deserving of particular attention are issues pertaining to the values of “service to the public” and “merit-based,” which rated poorly within all age cohorts and services, but especially so among the younger generations and women. Why do service members feel their institutions are lacking these attributes? What would they like to see changed? Digging into those questions and the remedial initiatives they may spur should be a priority for those aiming to strengthen Africa’s security institutions.

The results from this research also underscore the growing importance that peacekeeping operations are having on the identity and professionalization of Africa’s security sectors. The prospect for peacekeeping deployments plays an important motivational factor for young recruits and is an increasingly influential formative experience for service members and their institutions. As peacekeeping has taken on a more central responsibility in the mission of African security forces, their members have embraced this role and are eager to enhance their effectiveness and the lessons they can gain from these experiences. There is merit, therefore, in African governments and their international partners continuing to strengthen this capability.

In sum, the survey paints a generally positive picture. Africa’s security professionals are increasingly well-educated, dedicated to their careers and hungry to learn more. They see their profession as a calling and are eager to live up to its highest values. The challenge for the continent’s military and civilian leaders will be to harness this talent and energy to address the complex security challenges of the 21st century.

Dr. Kwesi Aning is the director of the faculty of academic affairs and research at the Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre in Accra, Ghana. Dr. Joseph Siegle is the director of research for the Africa Center for Strategic Studies in Washington, D.C.