Nigerian and Regional Efforts Helped Turn the Tide Against the Insurgent Group

ADF STAFF

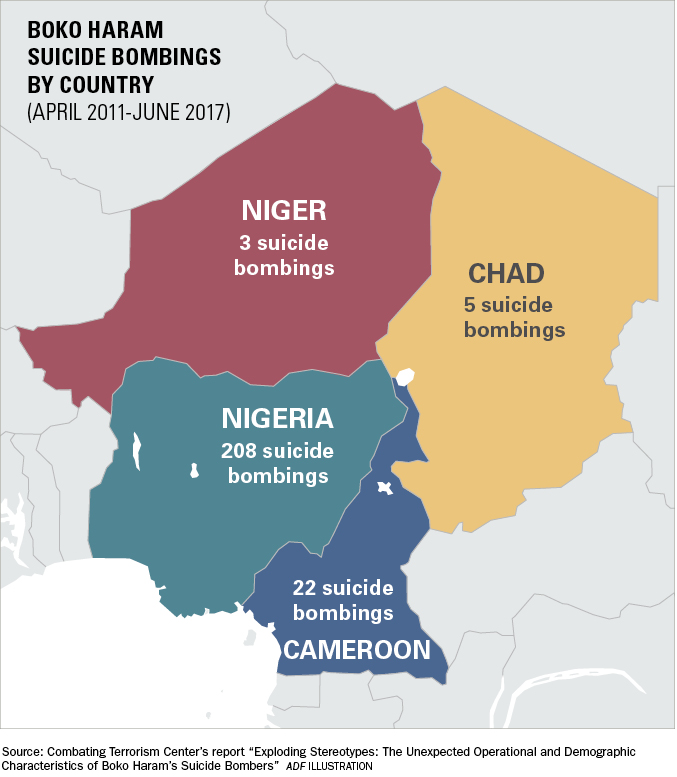

Boko Haram has left its mark in blood and destruction across Nigeria and in neighboring countries. The Islamist militant group has killed more than 20,000 people since emerging as a dangerous terrorist force in 2009. Its catalog of destruction almost defies description.

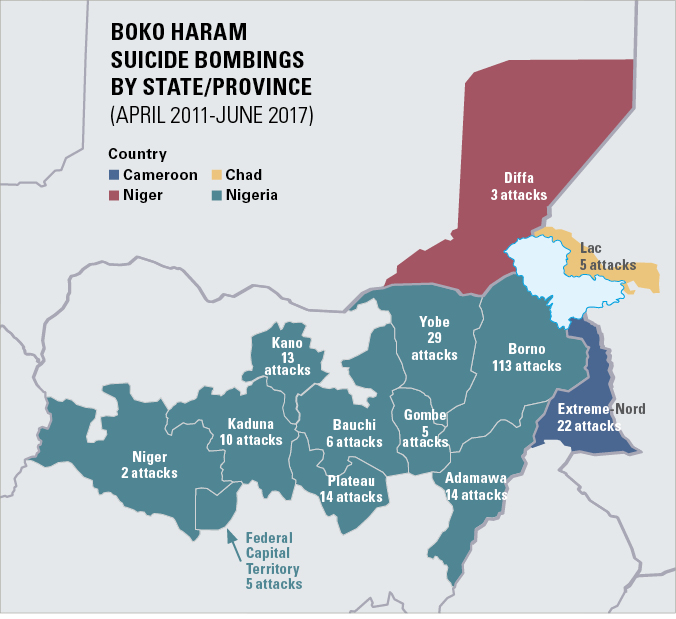

The catastrophic impact is nowhere more evident than in Nigeria’s northeastern Borno State. Its economic and social devastation is difficult to calculate, and yet a state government official released a tally of the losses in August 2017 in Maiduguri.

- About 1 million homes and public buildings in the state’s 27 local government areas.

- Properties worth $5.3 billion since 2011.

- 5,335 classrooms, 201 health centers, 1,630 water facilities, and 726 power stations and transformers.

- 800 public buildings such as offices, prisons, police posts and other buildings.

“The quantum of destruction caused by insurgents is monumental, resulting in serious humanitarian crisis,” Saleh said. “The damage calls for serious intervention from government, development and humanitarian organizations.”

The government, through the creation of the Ministry of Rehabilitation, Reconstruction and Resettlement, has rebuilt more than 25,000 homes in affected communities. It has also built classrooms, clinics, police offices, markets, roads, courts and places of worship in liberated communities, Saleh said. That work continues.

Boko Haram’s history is relatively short, but its murderous accomplishments are many. How did the insurgent group grow into such a deadly force?

Boko Haram’s history is relatively short, but its murderous accomplishments are many. How did the insurgent group grow into such a deadly force?

BOKO HARAM: A BRIEF HISTORY

Boko Haram’s roots date back generations in Nigeria. Its recent and more public history, however, can be traced to 2002. Its official Arab name, Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati wal-Jihad, means “People Committed to the Propagation of the Prophet’s Teachings and Jihad.” Its more common Hausa name simply means, “Western Education is Forbidden.”

The group spent its first seven years consolidating its base in Maiduguri and spreading its contempt for government corruption and Western education. It did so primarily by creating alternative schools and attacking things such as police stations to strike at “symbols of state power,” according to a 2013 Al-Jazeera report.

This all changed in 2009, when group leader Mohammed Yusuf was killed while in police custody after a raid. Boko Haram struck back at police in four states. By 2010, violence had begun to intensify, and in 2013 then-President Goodluck Jonathan declared an emergency in three states most affected by Boko Haram.

After Yusuf’s death, Boko Haram reorganized under the leadership of Abubakar Muhammad Shekau, who is credited with putting the group on a more extremist path in hopes of establishing an Islamic state across the country. He communicated through video messages that some said were similar to messages by Osama bin Laden. He is thought to have been killed by security forces on more than one occasion and hasn’t been seen in public since 2009.

After Yusuf’s death, Boko Haram reorganized under the leadership of Abubakar Muhammad Shekau, who is credited with putting the group on a more extremist path in hopes of establishing an Islamic state across the country. He communicated through video messages that some said were similar to messages by Osama bin Laden. He is thought to have been killed by security forces on more than one occasion and hasn’t been seen in public since 2009.

Shekau is said to communicate only with a select number of cell leaders. Even that contact is minimal, Nigerian journalist Ahmed Salkida told the BBC in 2014. “A lot of those calling themselves leaders in the group do not even have contact with him,” he said.

Still, his ruthlessness is evident. A 2014 video clip showed him laughing as he claimed responsibility for the abduction of more than 200 Nigerian schoolgirls in Chibok. “I abducted your girls,” he said, according to the BBC. “I will sell them in the market, by Allah. I will sell them off and marry them off.”

Still, his ruthlessness is evident. A 2014 video clip showed him laughing as he claimed responsibility for the abduction of more than 200 Nigerian schoolgirls in Chibok. “I abducted your girls,” he said, according to the BBC. “I will sell them in the market, by Allah. I will sell them off and marry them off.”

By 2015, however, Boko Haram leadership showed evidence of changing. Abu Musab al-Barnawi, the son of founder Yusuf, appeared in January 2015 as the group’s spokesman, less than two months before Shekau pledged the group’s allegiance to the Islamic State. By late summer 2016, the Islamic State had announced that al-Barnawi was Boko Haram’s new leader. It’s unclear what became of Shekau, although he has surfaced in video messages claiming that he has not been replaced, the BBC reported. He is said to now be leading a separate, and less consequential, faction of Boko Haram.

Al-Barnawi’s leadership comes at a time when the Nigerian military and forces from other Lake Chad basin nations have made gains against the extremist group.

THE MULTINATIONAL JOINT TASK FORCE

Security concerns in northern Nigeria and surrounding countries are nothing new. In 1994, the Lake Chad Basin Commission (LCBC) decided to form the Multinational Joint Security Force to combat cross-border banditry in the region. But it was four years later before the force took shape. “The force remained relatively lethargic, restricted to the organization of a few patrols,” according to a September 2016 Institute for Security Studies (ISS) report.

In 2012, the LCBC updated the force’s mandate to combat Boko Haram. In October 2014, the force was renamed the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) as LCBC countries Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria, as well as Benin, met in Niamey, Niger, to discuss deploying a multinational force and establishing a command headquarters to combat Boko Haram. The extremists, by then, had become a regional problem, not just a Nigerian concern.

By mid-2015, the heads of state and government of the LCBC and Benin met in Abuja, Nigeria, and adopted a concept of operations, command structure and a command headquarters, according to the ISS. Nigeria won the right to command the force for its duration because Boko Haram mostly operates in Nigeria. Cameroon filled the position of deputy force commander, and the MNJTF command headquarters was established in N’Djamena, Chad.

By mid-2015, the heads of state and government of the LCBC and Benin met in Abuja, Nigeria, and adopted a concept of operations, command structure and a command headquarters, according to the ISS. Nigeria won the right to command the force for its duration because Boko Haram mostly operates in Nigeria. Cameroon filled the position of deputy force commander, and the MNJTF command headquarters was established in N’Djamena, Chad.

The size of the MNJTF has varied since its inception, starting with 7,500, growing to 8,700 and leveling off at about 10,000 personnel. As of August 2015, ISS estimates put each country’s contribution as follows: Benin, 150; Cameroon, 2,450; Chad, 3,000; Niger, 1,000; and Nigeria, 3,000.

The ISS reports that MNJTF patrols began in November 2015, but that large-scale operations began in February 2016. Now the MNJTF has attracted attention outside Africa. French officials traveled to N’Djamena in July 2017 to meet with task force commanders. French Minister of the Armed Forces Florence Parly said the purpose of the visit was to congratulate the MNJTF and to learn how to administer efforts to combat instability in the Sahel region through the G5 Sahel Joint Task force, according to Global Sentinel. Brig. Gen. Moussa Mahamat Djoui, MNJTF deputy force commander, said success has been based on trust, commitment and the timely sharing of intelligence among staff members.

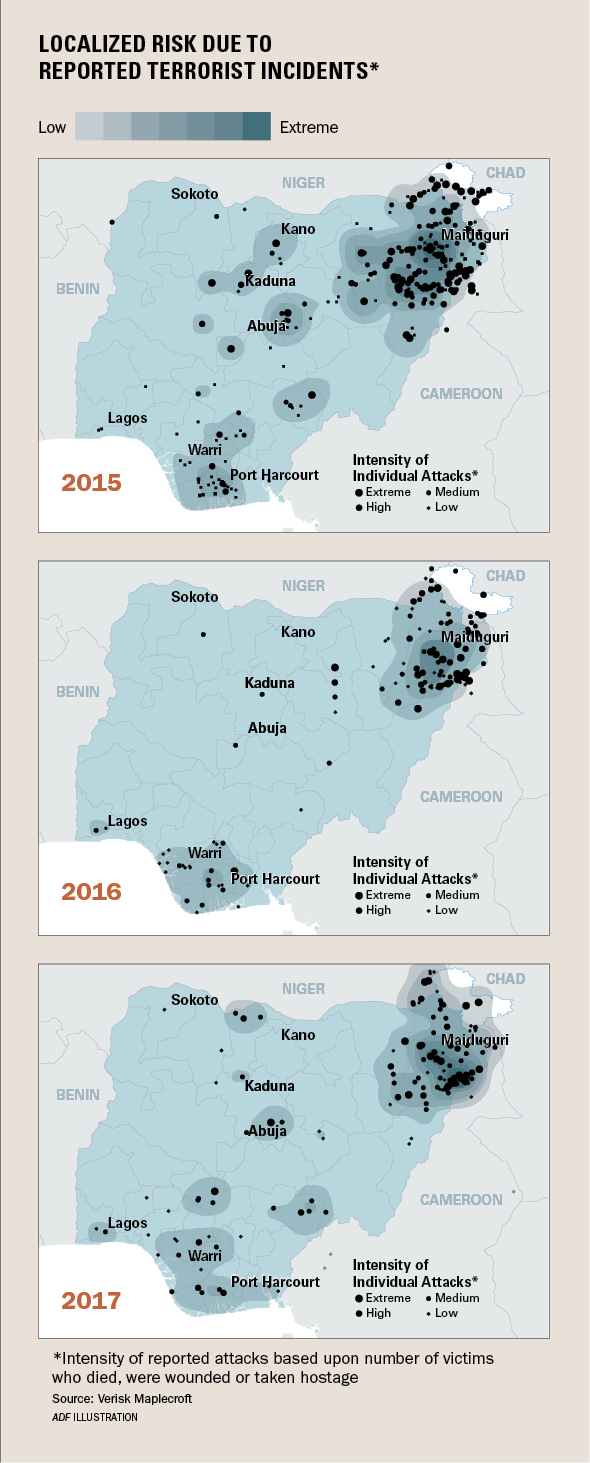

PROGRESS MADE; WORK TO DO

The work of the Nigerian military and the MNJTF has been essential in degrading Boko Haram as a front-line fighting force and as a holder of territory. David Doukhan, research fellow at the International Institute for Counter-Terrorism, wrote in October 2017 that military operations led to Boko Haram losing territory, ammunition, equipment, bases and manpower. Displaced residents have begun returning to the region.

Although the advances count as progress, Doukhan cautioned they should not be promoted as victory. Indeed, much work remains — beyond just military operations — to claim final victory against Boko Haram. “These structural changes, coupled with the Nigerian military offensive backed by the MNJTF, forced the terrorist group to return to its initial decentralized organizational structure, which renders military operations more complicated,” he wrote, “but the radical ideology is deeply embedded among the population.”

[AFP/GETTY IMAGES]

“The Nigerian army and the MNJTF struck blows of victory but did not achieve a knockout defeat. The path to peace is long,” Doukhan wrote. “Purging the region of radical jihadist ideology is feasible only through comprehensive and long-term treatment of the political, social, and economic factors that fuel the sympathy for the group and its radical ideology.”

A BOKO HARAM TIMELINE

2002 — Boko Haram organizes under Muslim cleric Mohammed Yusuf in Maiduguri, capital of Borno State.

December 2003 — In the first known Boko Haram attack, roughly 200 militants assault multiple police stations in Yobe State.

July 2009 — Boko Haram kills scores of police officers in Borno, Kano and Yobe states. A joint military task force kills more than 700 militants and destroys its operational mosque. Police capture the group’s leader, Mohammed Yusuf, who later dies in police custody. Police say they shot him during an escape attempt, but Boko Haram says it was an extrajudicial execution.

September 7, 2010 — Fifty Boko Haram militants attack a prison in Bauchi State, killing five and releasing more than 700 inmates.

June 16, 2011 — Boko Haram kills two in a car bomb attack on the Inspector-General of the Nigerian Police Force office in Abuja, in what is thought to be the first suicide attack in Nigeria.

August 26, 2011 — A Boko Haram car bomb kills 23 and injures more than 75 during an attack at the United Nations compound in Abuja.

November 4, 2011 — Militants detonate improvised explosive devices and car bombs, targeting security forces and their offices, markets, and 11 churches, killing more than 100 in attacks in Yobe Damaturu and Borno states.

January 20, 2012 — Boko Haram launches coordinated attacks against the military, police, a prison and other targets in Kano State, killing more than 200.

April 30, 2012 — The Lake Chad Basin Commission (LCBC) reactivates and expands the mandate of the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) so it can fight Boko Haram.

April 19, 2013 — Boko Haram battles security forces from Chad, Niger and Nigeria in Baga, Borno State, killing nearly 200 people.

June 4, 2013 — Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan lists Boko Haram and splinter group Ansaru as terrorist organizations.

August 14, 2013 — Nigeria’s Ministry of Defence announces that Boko Haram’s second in command, Momodu Baba (known as Abu Saad), has been killed.

April 14, 2014 — Boko Haram militants kidnap 276 teenage girls from a boarding school in Chibok in Borno State, sparking global outrage and a social media campaign.

May 13, 2014 — Hundreds of militants storm three villages in Borno State. Villagers resist, killing more than 200 Boko Haram fighters.

July 17-20, 2014 — Boko Haram raids the Nigerian town of Damboa, killing 66 residents. More than 15,000 flee.

August 24, 2014 — In a video, Boko Haram leader Abubakar Muhammad Shekau proclaims a caliphate in northern Nigeria.

October 7, 2014 — The LCBC establishes the MNJTF under its current form in Niamey, Niger.

November 25, 2014 — The African Union Peace and Security Council (PSC) endorses activation of the MNJTF.

January 3, 2015 — Hundreds of Boko Haram gunmen seize the town of Baga, neighboring villages in northern Nigeria, and a multinational military base in a multiday raid, leaving up to 2,000 people dead.

January 29, 2015 — The PSC formally approves deployment of the MNJTF for 12 months, a move that has since been renewed.

March 7, 2015 — In an audio message purportedly from Shekau, Boko Haram pledges allegiance to ISIS.

March 12, 2015 — An ISIS spokesman announces that the caliphate has expanded to West Africa and that ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi has accepted Boko Haram’s pledge of allegiance.

April 28-April 30, 2015 — Nigerian troops rescue about 450 women and girls in the Sambisa Forest during an operation to destroy Boko Haram camps and rescue civilians.

May 25, 2015 — The MNJTF command headquarters is inaugurated in N’Djamena, Chad.

July 19, 2015 — Nigeria’s Army launches Operation Lafiya Dole, which means “peace through force” in Hausa, to fight Boko Haram. It replaces Operation Zaman Lafiya.

September 23, 2015 — The Nigerian military raids Boko Haram camps in two villages, rescuing 241 women and children and arresting 43 militants.

February 11-14, 2016 — Cameroon attacks a Boko Haram base in Ngoshe, Nigeria, neutralizing 162 militants, liberating about 100 hostages and seizing weapons in Operation Arrow 5.

March 2016 — Thousands of Cameroonian and Nigerian Soldiers launch Operation Tentacle to root out Boko Haram in the Sambisa Forest.

April 2016 — Nigeria launches Operation Safe Corridor to rehabilitate repentant and surrendered Boko Haram fighters.

April 2016 — Nigeria initiates Operation Crackdown to drive Boko Haram from the Sambisa Forest and surrounding border areas.

June 2016 — The Nigerian Air Force launches Operation Gama Aiki, which means “finish the job” in Hausa, as a follow-up to Operation Crackdown.

August 3, 2016 — ISIS publication al-Naba says Abu Musab al-Barnawi is the new leader of Boko Haram.

October 13, 2016 — Boko Haram militants hand over 21 Chibok schoolgirls after negotiations with the Nigerian government, the first mass release of any of the more than 200 girls kidnapped in April 2014.

May 6, 2017 — Boko Haram releases 82 Chibok schoolgirls after negotiations with the Nigerian government.

Sources: African Union, BBC, CNN, ISS, The Nation, J. Peter Pham, Pulse.ng, This Day Live, Vanguard, Voice of America