Tracking and Relieving Hunger Can Be a Challenge. The Key for Soldiers? Knowing Their Role

By the time the world hears about a famine, it’s probably too late.

International aid organizations say early alerts and rapid responses to food shortages are the only ways to save lives. Before the United Nations declared famine in Somalia in 2011, it had issued 16 warnings that danger was imminent. Those warnings mostly were ignored and, by the time famine officially was declared, 120,000 people had died.

“Once famine takes root, it’s that much harder to recover,” wrote Aryn Baker in Time magazine. “Yet the call to prevent famine is never as widely shouted, or eagerly responded to, as the urgent demands to stop it.”

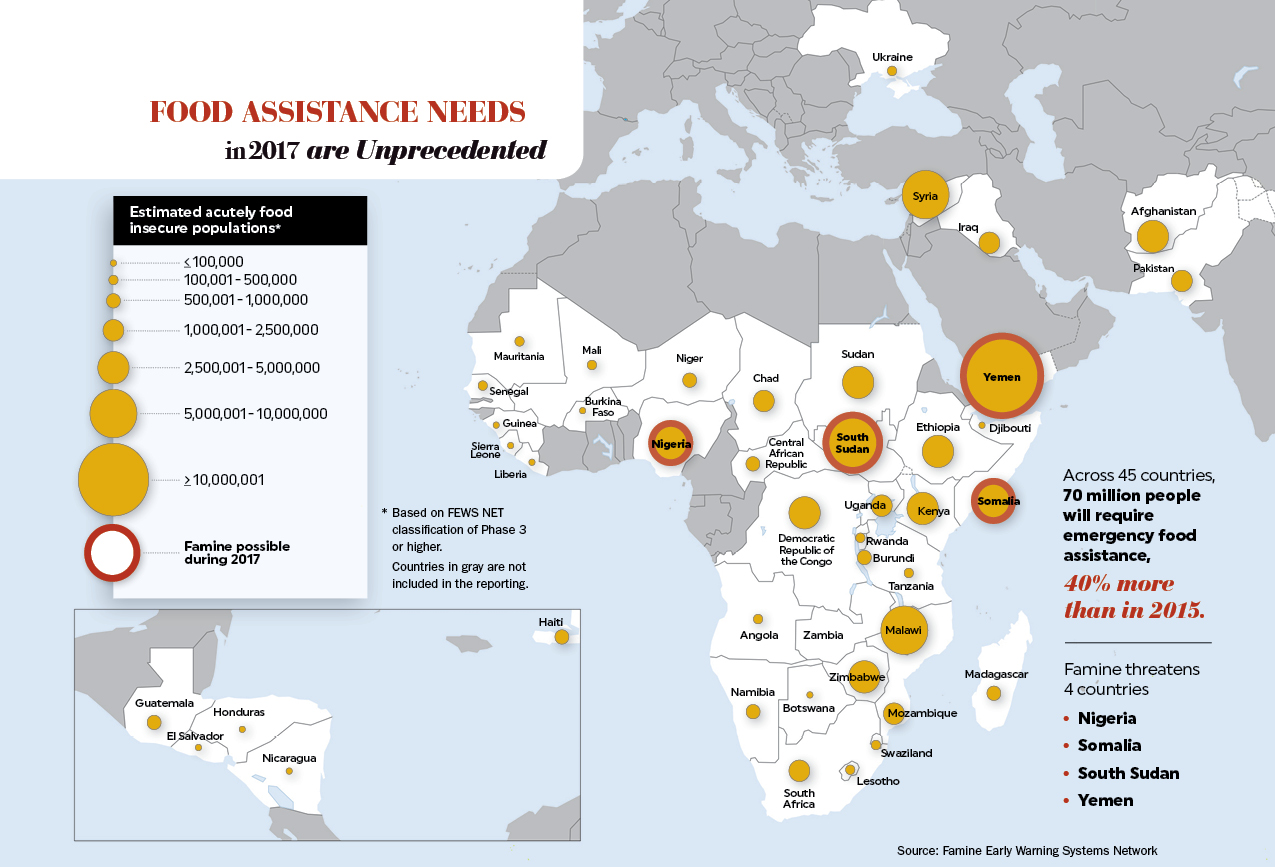

Famine is no stranger to Africa. In the 20th century alone, widespread hunger hit the continent no fewer than 18 times, killing anywhere from 5,000 to 1 million people at a time. In 2017, it struck again, this time in South Sudan — and to a lesser extent in northern Nigeria and Somalia — and the effects have been devastating.

In South Sudan, 100,000 people were on the verge of starvation as of February 2017, and 5 million people — 40 percent of the young nation’s population — needed immediate assistance.

“Our worst fears have been realized,” Serge Tissot, of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, told CNN. “Many families have exhausted every means they have to survive.” Another humanitarian aid official said people resorted to scavenging in swamps to find food.

The problem will continue in coming years as changing weather patterns, population growth and conflict threaten the continent’s fragile food security. So how can food crises be noticed early, and what role should security forces play in addressing them?

STAGES AND CAUSES

Famine is a particular term with a particular meaning. Its definition goes beyond just drought conditions and a large number of hungry people. Famine actually is the last stage in a five-step progression of food insecurity, according to the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET). The five stages grow over time — minimal, stressed, crisis and emergency, culminating with famine. A famine exists when at least one out of five households in an affected area faces an extreme lack of food, more than 30 percent of the population suffers acute malnutrition, and at least two out of 10,000 people die each day.

Famine was declared in part of South Sudan early in 2017, and three other countries — Nigeria, Somalia and Yemen — were at level four, meaning they were at high risk of developing famines.

The causes of famine can be just as complex as its stages. When drought, conflict or both strike a region, populations may be forced to migrate to other areas or into neighboring countries. A drought in an area already beset by conflict can disrupt harvests, planting or the care of livestock. Warring factions often block access to areas, which may keep humanitarian aid workers and residents from moving about freely. This can exacerbate existing problems.

A mass influx of people can strain resources and increase the spread of certain diseases, such as cholera. In southern Somalia, some villages still under al-Shabaab control have seen an increase in cholera cases, according to Voice of America (VOA). In May 2017, Somalia was reporting 200 to 300 cholera cases every day. More than 40,000 Somalis had fallen ill since December 2016, and half were in South West State.

In May 2017, medics visited more than 150,000 displaced people living in camps near Baidoa, Somalia. Many in the camps slept in the open without tarps. Stagnant water and mud were everywhere, and there was not enough clean water to go around. UNICEF and World Health Organization (WHO) personnel provided oral cholera vaccines to children. However, the ability to fight cholera and other diseases is connected to the ability to combat hunger and other humanitarian problems, Dr. Abdinasir Abubakar, cholera expert with the WHO, told VOA.

In May 2017, medics visited more than 150,000 displaced people living in camps near Baidoa, Somalia. Many in the camps slept in the open without tarps. Stagnant water and mud were everywhere, and there was not enough clean water to go around. UNICEF and World Health Organization (WHO) personnel provided oral cholera vaccines to children. However, the ability to fight cholera and other diseases is connected to the ability to combat hunger and other humanitarian problems, Dr. Abdinasir Abubakar, cholera expert with the WHO, told VOA.

“We cannot only solve cholera,” Abubakar said. “We cannot only deal with cholera unless we deal with food insecurity, unless we deal with water issues, malnutrition. … We are working closely and we are coordinating, but again in Somalia one of the challenges we are facing [is] a shortage of resources to support all these interventions.”

EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS

There are many ways to predict the likelihood of a famine. Weather data shows when annual rainfalls have been inadequate to water crops. Market data show when staple food items become scarce and more expensive.

Mass migration tells when people have been forced to flee their homes due to conflict, disease or ecological stressors.

FEWS NET has 22 field offices around the world monitoring these factors. They produce regular reports and issue warnings. When conflict or distance makes it difficult to access certain regions, the organization relies on local partners, satellite imagery and mobile phone technology to gather data. For example, FEWS NET launched a pilot project using cellphones to collect wage and market data in Madagascar to determine when laborers are in low demand, which signals a bad year for harvests. In other countries, FEWS NET has built farmer networks that relay information by phone.

“We’re piloting a variety of tools and I think technology can help us, but I would also say that there are limitations,” Chris Hillbruner of FEWS NET told VOA. “At the end of the day we still get the best information when people are able to go into these areas and get on the ground to collect information about what is happening.”

Other organizations are looking for ways to gather information about food insecurity in places that are too remote or too dangerous for observers to enter. The platform Tomnod, run by the satellite company DigitalGlobe, uses crowd-sourced analysis of satellite imagery to map data. The group has mapped satellite imagery across 18,000 square kilometers in South Sudan to identify permanent dwellings, temporary dwellings and livestock herds. The satellites produce high-quality images in which each pixel represents 30 centimeters on the ground. This mapping will help DigitalGlobe track the impact of the ongoing conflict and give an idea of where food insecurity is likely to occur.

“For humanitarians to cover that kind of ground, especially when it’s insecure, is just not a safe approach,” said Rhiannan Price, senior manager of DigitalGlobe’s Seeing a Better World Program. “Satellite imagery offers a really helpful tool when it comes to assessing and evaluating what’s happening on the ground, trying to find those folks so we can get resources and actually quantify the situation there.”

The Nutrition Early Warning System launched by the International Center for Tropical Agriculture tracks health and nutrition information to look for trends such as stunted growth in children, which may be a precursor to widespread food insecurity. The system is expected to be up and running in Ethiopia, Nigeria, Somalia and South Sudan by the end of 2017.

HOW SOLDIERS CAN HELP

Peacekeepers and military personnel often will be asked to help provide food assistance, but typically will not play the lead role. There are two main ways Soldiers can help ensure rapid response to famines: protection and coordination.

Protection

Lack of security prevents food from reaching those who need it. When aid workers are attacked or threatened, organizations typically remove their personnel. In April 2017, the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization pulled workers from some of South Sudan’s hardest-hit areas after three aid workers were killed.

“Attacks against aid workers and aid assets are utterly reprehensible,” said Eugene Owusu, the U.N.’s humanitarian chief in South Sudan. “They not only put the lives of aid workers at risk, they also threaten the lives of thousands of South Sudanese who rely on our assistance for their survival.”

Armed forces can provide security for humanitarian groups by protecting convoys as they move along roads, offering security at feeding stations or guarding boats coming into ports. One of the most visible examples of this is the European Union Naval Force’s Operation Atalanta, which has protected World Food Programme (WFP) vessels coming into and out of the Horn of Africa since 2008. Another example is the liberation of the port city of Kismayo, Somalia, in 2012 by African Union and Somali forces, which allowed the WFP to resume delivering aid for the first time in four years.

It’s not only aid workers who need protection; recipients of food aid can become targets as well. In Nigeria, Boko Haram has attacked villages to steal food aid and medicine. “Any delivery of aid had a high potential for a town to be attacked and supplies raided,” Karen Attiah, global opinions editor for The Washington Post, said during a forum at the Brookings Institution. “That’s a perennial problem of providing support to these areas. How do you do it without strengthening the terrorists you’re trying to fight and without making the recipients a target?”

Coordination

Armed forces and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) are structured differently. Militaries operate as strict hierarchies and tend to seek quick impact and short-term engagement. NGOs’ structure empowers lower-level workers, and those workers prefer to retain independence to avoid arousing the suspicion of those they are trying to help, according to the Guide to Nongovernmental Organizations for the Military, edited and co-written by health and human rights expert Lynn Lawry.

The goal of both groups is protecting the public, and it is helpful if they can work together.

Shantal Persaud, deputy spokesperson for the U.N. Mission in South Sudan, said peacekeepers are not mandated to help provide famine relief. But in any such mission, peacekeepers will encounter humanitarian actors.

The key is to integrate the efforts of everyone serving the mission, Persaud said. This is achieved through training, and then practicing the integration in the field. “Peacekeepers and humanitarians do not operate in silos and are integrated at the outset by conduct of integrated induction training, which is mandatory for all and carried out by the in-house Integrated Mission Training Centre,” she said.

Security professionals should not be surprised when humanitarian organizations choose to stay at a distance. In Somalia, 13 aid workers were kidnapped in April 2017 by al-Shabaab, which suspected them of being government informants. Working for international aid groups makes locals a target. Working alongside security forces could make them even bigger targets.

“If they caught me, they would kill me,” a Somali employee of Save the Children told The Washington Post. “It’s that simple.”